Error message

- Warning: Undefined array key 0 in Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances() (line 388 of modules/contrib/footnotes/src/Plugin/Filter/FootnotesFilter.php).

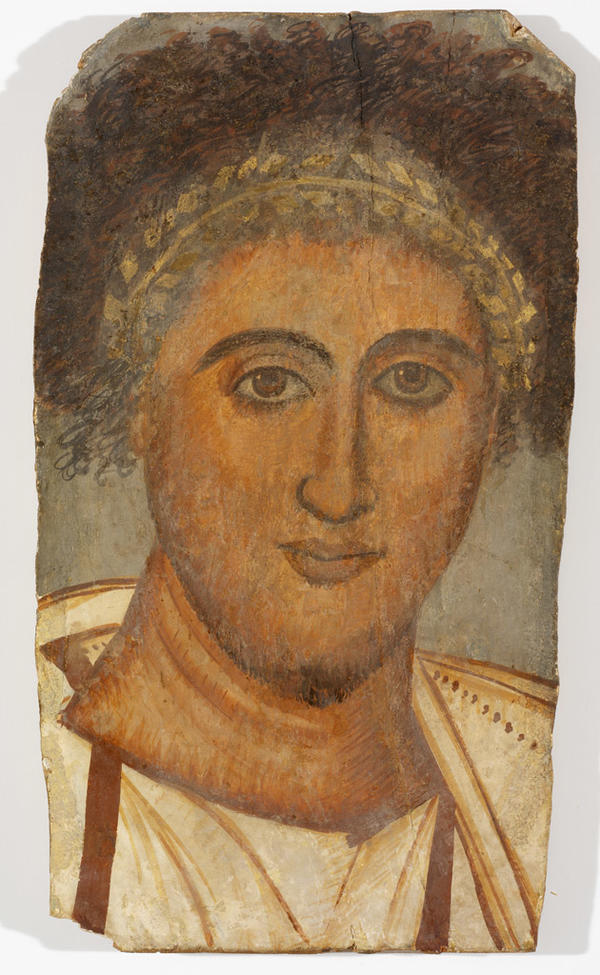

Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances('Agrippina the Younger watches as men of the emperor move nearer and nearer to her. They carry weapons. Having survived one attempt on her life, she knows that she will not survive another. One man knocks her over the head with a club and another raises his sword. With her last breath, she implores her killers to strike through her womb— the womb that birthed Nero, her matricidal son. <em>The Remorse of Nero After Killing his Mother</em> by John William Waterhouse Public domain, source: http://www.wikiart.org/en/john-william-waterhouse/the-remorse-of-nero-after-the- murder-of-his-mother-1878, in which Nero realizes that maybe killing his mother 1 wasn’t a nice thing to do. Image courtesy of The Victorian Web This account of Agrippina’s death, corroborated by several ancient historians but likelyC.f., Tacitus 14; Dio 12.12-14. embellished, previews the difficulties we will face in exploring Agrippina in the historical record. Why does Agrippina asked to be stabbed through the womb? Yes, she birthed Nero, but could her last plea also represent a Lady Macbeth-esque desire to unsex herself—a metonymic exhortation to destroy that which made her a woman? Is this question of any import to her portrait at the RISD Museum? Turning first to how contemporary revisionist historians have begun to view earlier historians of Agrippina, I will then look at the role of Agrippina’s portrait as a living cultural artifact inextricably linked with certain changes in the historical reception of Agrippina. Agrippina the Younger (15–59 CE) was closely connected to the first five Roman emperors: she was great-granddaughter of Augustus, great-niece and adoptive granddaughter of Tiberius, sister of Caligula, niece and fourth wife of Claudius, and mother of Nero. Beyond her noble status, Agrippina demanded “real and official power” and not mere “influence.” That Agrippina faces a hostile historical record isImperial Women 259. beyond debate and related to her demands for this sort of power. Since Suetonius andIbid; I, Claudia 62. Tacitus, she has been characterized as bloodthirsty, overly ambitious, sexually flagrant, and unfeminine; and accused of crimes from murder to incest.Imperial Women, 1. Susan Wood, who has written much on Agrippina the Younger and other Roman women, traces this hostile historical record, above all else, to Agrippina’s encroachment on traditionally male privileges, and colorfully points to prejudices and inaccuracies in many of the accusations against her. I would like to focus first on Wood’s assertionImperial Women 259. that the frequency that powerful and intelligent woman faced nearly identical accusations renders them suspect. Such depictions of these women, which still abound in AmericanImperial Women 262 politics today, stem from actual misogyny or a desire to use a stereotype as an easy rhetorical shortcut. Second, Wood holds that the structure of Roman society encouraged its women to act indirectly. Direct avenues of holding power were closed off to women and thus, if they wanted to exercise power, they were forced to pursue “devious and manipulative forms of behavior.” While not exonerating Agrippina from all blame— even the most revisionist of historians agree that she was still guilty of many crimes— we should look critically on accusations against her, in particular those that follow a predictable pattern. Understanding Agrippina’s legacy in the contemporary historical debate prepares us to more fully appreciate the RISD Museum's portrait of Agrippina, its role (or roles) in this muddled historical record, and what it means to the viewer today. Since the move away from more realistic representations under Augustus, Roman portraiture began to be used as a tool for communicating ideologies.www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ropo2/hd_ropo2.htm What sort of ideology does Agrippina’s portrait communicate? First of all, we must ask who commissioned the statue, and thus who was doing the communicating. We can’t be sure that Agrippina commissioned the statue, or when in her life it would have been commissioned. Museum records date the piece to circa 40 CE. If dated before Caligula’s death, it could have been commissioned by Caligula himself. In this case, the statue would have acted as part of Caligula’s plan to elevate Agrippina, Drusilla, and his other sisters.. Through this Cult of Drusilla, Caligula sought to set up his sisters as objects of veneration in order to cement his own rule and power.Barrett 225; “Diva Drusilla Panthea and the Sisters of Caligula”. They were invoked with Caligula in public oaths and, together with Antonia the Younger, were the first to be granted privileges normally accorded to the Vestal Virgins.Behen 62 We can see an example of such a depiction on the backside of the coin belowBarret 225; Source of image: http://www.wildwinds.com/coins/sear5/s1800.html: <a href="https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Caligula_sestertius_RIC_33_680999.jpg">Sestertius from rule of Caligula. Front: Germanicus; Back: Agrippina the Younger and her sisters.</a> However, if we suppose that the statue was commissioned by Agrippina, the function is altered and Agrippina is the one in control of manipulating her own image. This portrait and other commissioned by Agrippina can as Curator of Ancient Art Gina Borromeo writes, “give us an idea of how she wished to be portrayed.”Borromeo, “Looking an Empress in the Eye.” Given that Agrippina’ autobiography was destroyed,Borromeo, “Looking an Empress in the Eye.” this piece might be able to grant us invaluable insight into understanding a figure so prejudiced by the historical record, as she herself wished to be perceived. In any case, one should be no less critical here than with the rest of the historical record, and we can only suggest this as one possible interpretation. Presuming that Agrippina commissioned the portrait, it seems unlikely that it was when Agrippina’s power was most threatened. From late 39 to January 41, she was exiled by her brother Caligula. It might be the case that this statue was a part of an effort by Agrippina to reconsolidate her power upon returning from exile. It is interesting to entertain the idea that this might be from a year as late as 49 — after she married Claudius and become empress but that seems unlikely, as other statues we have from that period display evidence of an imperial diadem.Behen 63. The idea that Agrippina commissioned the portrait can be supported with close inspection. The portrait seems to depart from the faceless, unassuming Vestal Virgin of the sestertius minted under Caligula. She does not ask us to idealize her as some feminine standard of beauty; rather, she presents herself as “rather jowly” with “heavy features” and a “large nose,”Barrett 225. and there is a “certain asymmetry in her features” and especially the nose.Ridgway 201. This could be a response to gossip that circulated against her, as a woman and of which she might have had some awareness. As contemporary biographer Anthony A. Barrett observes, her attractiveness is not a “trivial issue” when historians such as Tacitus claimed that she was a “beautiful woman” who used her “physical charms to ensnare a defenseless Claudius, among others.”Barrett 225. Agrippina looks determined, fearless, and perhaps even disdainful. The severe eyebrows extend horizontally to the hairline and dislocate the forehead, and elevate the corner of the brows in a way that lend force to this expression.Ridgway 201. Running parallel from a center part, the tresses of hair becomes tighter as it moves towards the ears.Ibid. This style possibly evokes, as it does in other portraits of her,Behen 63. that of Agrippina’s mother who was also politically powerful and suffered exile. The allusion to her mother’s hairstyle would have presumably been more apparent to those who lived in Rome who grew up around representations of Agrippina the Elder. In drawing comparison to her mother, Agrippina the Younger insists on her noble lineage and right to wield authority, even as a woman; she anticipates the future power that she would one day hold and had pretensions of holding and legitimizes her right to that power by invocation. Similarly her protruding upper lip and small chin recall depictions of her brother Caligula, Behen 62. and these resemblances seek to further highlight her dynastic right to rule. The bust of the statue—including the taupe tunic, green mantle, and socle (or simple pedestal)—is not ancient but likely from the 18th century and parallels other portraits we have from this era.Borromeo, “Looking an Empress in the Eye.” In addition to this theory, this article also contains a more detailed treatment of the 18th century additions. What does the addition say about 18th century tastes and perceptions of this portrait, and the larger question of how historical forces can shape perceptions of an object? To begin to answer these questions, one must first understand 18th century restoration practices. Often broken statutes were mended with new creations (for another example, the RISD Museum’s <em>Figure in the Guise of Hermes</em>; both the ancient body and removed leg of 18th century origin can be viewed in the Ancient Art Gallery). The addition of the bust in the case of the Agrippina perhaps was responding to a need to more easily display the piece and a perceived lack of color. The RISD Museum acquired the piece from a Marchioness of Linlithgow and before that it was probably proudly exhibited by many other wealthy individuals. Here these individuals used this piece in a similar manner to how we guessed Agrippina might have—to highlight nobility and power. These perceived deficiencies unawarely hit on the part that the portrait played in antiquity. As Borromeo elucidates, ancient statues of white marble were typically painted in vivid colors, thus this 18th century addition incidentally gives the contemporary museumgoer some indication of the effect that color would have added.Borromeo, “Looking an Empress in the Eye.” While this proves to be an interesting historical coincidence, one would err to imagine that this negates the history of this object and reverts it to some earlier form; rather, these additions present a visual manifestation of how viewers of different periods can bring something of their own age to a work, so as to inscribe new meaning and shed light on aspects that have long laid dormant. As the literary critic and theorist Stephen Greenblatt states, “Cultural artifacts do not stay still, . . . they exist in time, and . . . they are bound up with personal and institutional conflicts, negotiations, and appropriations.” One would be remiss to see Agrippina’s portrait at the RISD Museum and assume its significance was locked up in Imperial Rome. Commenting on the legacy of Agrippina, Barrett questions whether she was ever able to escape a “devastating ‘image’ problem.”Barrett 225. Like Wood, he views her manipulation as necessary—although not excusable—in the misogynistic culture that she faced. Successful manipulation was not only a matter of publicity but also of life and death. She excelled in this manipulation as the wife of Claudius but “tragically failed” as the life of Nero, leading to the death described at the beginning of this essay. In her own time, Barrett concludes, “She did not change the hardened attitude of her contemporaries, but she did define what Romans were willing to tolerate.” In a similar way, her portrait measures what the people of various ages are willing to tolerate, and mirrors and even influences social and cultural processes. The recent revisionist work of historians such as Wood and Barrett opens up to us new hermeneutic possibilities that reflect larger developments and processes of our times. On the other hand, we should avoid presenting our own age as superior. As media coverage of the 2016 American presidential election reminds us, it is all too easy to let misleading tropes color perception. Although it cannot be said that, when it comes to attitudes about women, American society is fully beyond the hardened attitudes of Imperial Rome, examining how other ages received Agrippina and her portrait can alert us to systemic flaws in our own thought processes. Bibliography Behen, Michael J., in Diana Kleiner and Susan Matheson, eds. I Claudia: Women in Ancient Rome (New Haven, 1996), 62-63. Barrett, Anthony. Agrippina. Florence, US: Routledge, 2002. ProQuest ebrary. Web. 15 May 2016. Borromeo, Gina. “Looking an Empress in the Eye,” RISD Museum Manual. Web. May 2016 Clark, A. M., “An Agrippina,” Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design, Museum Notes 44 (May 1958) 3–5, 10. Ridgway, Brunilde S., Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Classical Sculpture (Providence, 1972) 86–87, 201–204. Trentinella, Rosemarie. “Roman Portrait Sculpture: The Stylistic Cycle.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. www.metmuseum.org/toah/ hd/ropo2/hd_ropo2.htm (October 2003) Wood, Susan E., “Diva Drusilla Panthea and the Sisters of Caligula,” American Journal of Archaeology 99 (1995): 457–82. Wood, Susan E., Imperial Women: A Study in Public Images, 40 BC–AD 68 (Boston, 1999), with earlier references. ') (Line: 116) Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->process('Agrippina the Younger watches as men of the emperor move nearer and nearer to her. They carry weapons. Having survived one attempt on her life, she knows that she will not survive another. One man knocks her over the head with a club and another raises his sword. With her last breath, she implores her killers to strike through her womb— the womb that birthed Nero, her matricidal son. <em>The Remorse of Nero After Killing his Mother</em> by John William Waterhouse Public domain, source: http://www.wikiart.org/en/john-william-waterhouse/the-remorse-of-nero-after-the- murder-of-his-mother-1878, in which Nero realizes that maybe killing his mother 1 wasn’t a nice thing to do. Image courtesy of The Victorian Web This account of Agrippina’s death, corroborated by several ancient historians but likelyC.f., Tacitus 14; Dio 12.12-14. embellished, previews the difficulties we will face in exploring Agrippina in the historical record. Why does Agrippina asked to be stabbed through the womb? Yes, she birthed Nero, but could her last plea also represent a Lady Macbeth-esque desire to unsex herself—a metonymic exhortation to destroy that which made her a woman? Is this question of any import to her portrait at the RISD Museum? Turning first to how contemporary revisionist historians have begun to view earlier historians of Agrippina, I will then look at the role of Agrippina’s portrait as a living cultural artifact inextricably linked with certain changes in the historical reception of Agrippina. Agrippina the Younger (15–59 CE) was closely connected to the first five Roman emperors: she was great-granddaughter of Augustus, great-niece and adoptive granddaughter of Tiberius, sister of Caligula, niece and fourth wife of Claudius, and mother of Nero. Beyond her noble status, Agrippina demanded “real and official power” and not mere “influence.” That Agrippina faces a hostile historical record isImperial Women 259. beyond debate and related to her demands for this sort of power. Since Suetonius andIbid; I, Claudia 62. Tacitus, she has been characterized as bloodthirsty, overly ambitious, sexually flagrant, and unfeminine; and accused of crimes from murder to incest.Imperial Women, 1. Susan Wood, who has written much on Agrippina the Younger and other Roman women, traces this hostile historical record, above all else, to Agrippina’s encroachment on traditionally male privileges, and colorfully points to prejudices and inaccuracies in many of the accusations against her. I would like to focus first on Wood’s assertionImperial Women 259. that the frequency that powerful and intelligent woman faced nearly identical accusations renders them suspect. Such depictions of these women, which still abound in AmericanImperial Women 262 politics today, stem from actual misogyny or a desire to use a stereotype as an easy rhetorical shortcut. Second, Wood holds that the structure of Roman society encouraged its women to act indirectly. Direct avenues of holding power were closed off to women and thus, if they wanted to exercise power, they were forced to pursue “devious and manipulative forms of behavior.” While not exonerating Agrippina from all blame— even the most revisionist of historians agree that she was still guilty of many crimes— we should look critically on accusations against her, in particular those that follow a predictable pattern. Understanding Agrippina’s legacy in the contemporary historical debate prepares us to more fully appreciate the RISD Museum's portrait of Agrippina, its role (or roles) in this muddled historical record, and what it means to the viewer today. Since the move away from more realistic representations under Augustus, Roman portraiture began to be used as a tool for communicating ideologies.www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ropo2/hd_ropo2.htm What sort of ideology does Agrippina’s portrait communicate? First of all, we must ask who commissioned the statue, and thus who was doing the communicating. We can’t be sure that Agrippina commissioned the statue, or when in her life it would have been commissioned. Museum records date the piece to circa 40 CE. If dated before Caligula’s death, it could have been commissioned by Caligula himself. In this case, the statue would have acted as part of Caligula’s plan to elevate Agrippina, Drusilla, and his other sisters.. Through this Cult of Drusilla, Caligula sought to set up his sisters as objects of veneration in order to cement his own rule and power.Barrett 225; “Diva Drusilla Panthea and the Sisters of Caligula”. They were invoked with Caligula in public oaths and, together with Antonia the Younger, were the first to be granted privileges normally accorded to the Vestal Virgins.Behen 62 We can see an example of such a depiction on the backside of the coin belowBarret 225; Source of image: http://www.wildwinds.com/coins/sear5/s1800.html: <a href="https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Caligula_sestertius_RIC_33_680999.jpg">Sestertius from rule of Caligula. Front: Germanicus; Back: Agrippina the Younger and her sisters.</a> However, if we suppose that the statue was commissioned by Agrippina, the function is altered and Agrippina is the one in control of manipulating her own image. This portrait and other commissioned by Agrippina can as Curator of Ancient Art Gina Borromeo writes, “give us an idea of how she wished to be portrayed.”Borromeo, “Looking an Empress in the Eye.” Given that Agrippina’ autobiography was destroyed,Borromeo, “Looking an Empress in the Eye.” this piece might be able to grant us invaluable insight into understanding a figure so prejudiced by the historical record, as she herself wished to be perceived. In any case, one should be no less critical here than with the rest of the historical record, and we can only suggest this as one possible interpretation. Presuming that Agrippina commissioned the portrait, it seems unlikely that it was when Agrippina’s power was most threatened. From late 39 to January 41, she was exiled by her brother Caligula. It might be the case that this statue was a part of an effort by Agrippina to reconsolidate her power upon returning from exile. It is interesting to entertain the idea that this might be from a year as late as 49 — after she married Claudius and become empress but that seems unlikely, as other statues we have from that period display evidence of an imperial diadem.Behen 63. The idea that Agrippina commissioned the portrait can be supported with close inspection. The portrait seems to depart from the faceless, unassuming Vestal Virgin of the sestertius minted under Caligula. She does not ask us to idealize her as some feminine standard of beauty; rather, she presents herself as “rather jowly” with “heavy features” and a “large nose,”Barrett 225. and there is a “certain asymmetry in her features” and especially the nose.Ridgway 201. This could be a response to gossip that circulated against her, as a woman and of which she might have had some awareness. As contemporary biographer Anthony A. Barrett observes, her attractiveness is not a “trivial issue” when historians such as Tacitus claimed that she was a “beautiful woman” who used her “physical charms to ensnare a defenseless Claudius, among others.”Barrett 225. Agrippina looks determined, fearless, and perhaps even disdainful. The severe eyebrows extend horizontally to the hairline and dislocate the forehead, and elevate the corner of the brows in a way that lend force to this expression.Ridgway 201. Running parallel from a center part, the tresses of hair becomes tighter as it moves towards the ears.Ibid. This style possibly evokes, as it does in other portraits of her,Behen 63. that of Agrippina’s mother who was also politically powerful and suffered exile. The allusion to her mother’s hairstyle would have presumably been more apparent to those who lived in Rome who grew up around representations of Agrippina the Elder. In drawing comparison to her mother, Agrippina the Younger insists on her noble lineage and right to wield authority, even as a woman; she anticipates the future power that she would one day hold and had pretensions of holding and legitimizes her right to that power by invocation. Similarly her protruding upper lip and small chin recall depictions of her brother Caligula, Behen 62. and these resemblances seek to further highlight her dynastic right to rule. The bust of the statue—including the taupe tunic, green mantle, and socle (or simple pedestal)—is not ancient but likely from the 18th century and parallels other portraits we have from this era.Borromeo, “Looking an Empress in the Eye.” In addition to this theory, this article also contains a more detailed treatment of the 18th century additions. What does the addition say about 18th century tastes and perceptions of this portrait, and the larger question of how historical forces can shape perceptions of an object? To begin to answer these questions, one must first understand 18th century restoration practices. Often broken statutes were mended with new creations (for another example, the RISD Museum’s <em>Figure in the Guise of Hermes</em>; both the ancient body and removed leg of 18th century origin can be viewed in the Ancient Art Gallery). The addition of the bust in the case of the Agrippina perhaps was responding to a need to more easily display the piece and a perceived lack of color. The RISD Museum acquired the piece from a Marchioness of Linlithgow and before that it was probably proudly exhibited by many other wealthy individuals. Here these individuals used this piece in a similar manner to how we guessed Agrippina might have—to highlight nobility and power. These perceived deficiencies unawarely hit on the part that the portrait played in antiquity. As Borromeo elucidates, ancient statues of white marble were typically painted in vivid colors, thus this 18th century addition incidentally gives the contemporary museumgoer some indication of the effect that color would have added.Borromeo, “Looking an Empress in the Eye.” While this proves to be an interesting historical coincidence, one would err to imagine that this negates the history of this object and reverts it to some earlier form; rather, these additions present a visual manifestation of how viewers of different periods can bring something of their own age to a work, so as to inscribe new meaning and shed light on aspects that have long laid dormant. As the literary critic and theorist Stephen Greenblatt states, “Cultural artifacts do not stay still, . . . they exist in time, and . . . they are bound up with personal and institutional conflicts, negotiations, and appropriations.” One would be remiss to see Agrippina’s portrait at the RISD Museum and assume its significance was locked up in Imperial Rome. Commenting on the legacy of Agrippina, Barrett questions whether she was ever able to escape a “devastating ‘image’ problem.”Barrett 225. Like Wood, he views her manipulation as necessary—although not excusable—in the misogynistic culture that she faced. Successful manipulation was not only a matter of publicity but also of life and death. She excelled in this manipulation as the wife of Claudius but “tragically failed” as the life of Nero, leading to the death described at the beginning of this essay. In her own time, Barrett concludes, “She did not change the hardened attitude of her contemporaries, but she did define what Romans were willing to tolerate.” In a similar way, her portrait measures what the people of various ages are willing to tolerate, and mirrors and even influences social and cultural processes. The recent revisionist work of historians such as Wood and Barrett opens up to us new hermeneutic possibilities that reflect larger developments and processes of our times. On the other hand, we should avoid presenting our own age as superior. As media coverage of the 2016 American presidential election reminds us, it is all too easy to let misleading tropes color perception. Although it cannot be said that, when it comes to attitudes about women, American society is fully beyond the hardened attitudes of Imperial Rome, examining how other ages received Agrippina and her portrait can alert us to systemic flaws in our own thought processes. Bibliography Behen, Michael J., in Diana Kleiner and Susan Matheson, eds. I Claudia: Women in Ancient Rome (New Haven, 1996), 62-63. Barrett, Anthony. Agrippina. Florence, US: Routledge, 2002. ProQuest ebrary. Web. 15 May 2016. Borromeo, Gina. “Looking an Empress in the Eye,” RISD Museum Manual. Web. May 2016 Clark, A. M., “An Agrippina,” Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design, Museum Notes 44 (May 1958) 3–5, 10. Ridgway, Brunilde S., Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Classical Sculpture (Providence, 1972) 86–87, 201–204. Trentinella, Rosemarie. “Roman Portrait Sculpture: The Stylistic Cycle.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. www.metmuseum.org/toah/ hd/ropo2/hd_ropo2.htm (October 2003) Wood, Susan E., “Diva Drusilla Panthea and the Sisters of Caligula,” American Journal of Archaeology 99 (1995): 457–82. Wood, Susan E., Imperial Women: A Study in Public Images, 40 BC–AD 68 (Boston, 1999), with earlier references. ', 'en') (Line: 118) Drupal\filter\Element\ProcessedText::preRenderText(Array) call_user_func_array(Array, Array) (Line: 111) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doTrustedCallback(Array, Array, 'Render #pre_render callbacks must be methods of a class that implements \Drupal\Core\Security\TrustedCallbackInterface or be an anonymous function. The callback was %s. See https://www.drupal.org/node/2966725', 'exception', 'Drupal\Core\Render\Element\RenderCallbackInterface') (Line: 797) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doCallback('#pre_render', Array, Array) (Line: 386) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 106) __TwigTemplate_4039b6d648e4a30fc59604b38849a688->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 46) __TwigTemplate_d1494d795b4bd5366283e85f3e7729dc->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 43) __TwigTemplate_253b62141ad73ee07345b0067cf59829->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/contrib/classy/templates/field/field--text-with-summary.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('field', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 231) __TwigTemplate_d0a4e06ec4cdc862487a9e59e7ee55e6->block_node_content(Array, Array) (Line: 171) Twig\Template->displayBlock('node_content', Array, Array) (Line: 91) __TwigTemplate_fb45c12c057c90d6dad87acc3f8af627->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 51) __TwigTemplate_d0a4e06ec4cdc862487a9e59e7ee55e6->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/content/node--teaser.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('node', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 60) __TwigTemplate_b5820ae2fc9ac809d8bb920432eaa798->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/contrib/classy/templates/views/views-view-unformatted.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('views_view_unformatted', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 110) __TwigTemplate_fc3dc095246a9d6d2c8632ac77f62c14->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/contrib/classy/templates/views/views-view.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('views_view', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 74) __TwigTemplate_c81e6485dadaf75052a00079fc772d9e->block_content(Array, Array) (Line: 171) Twig\Template->displayBlock('content', Array, Array) (Line: 62) __TwigTemplate_c81e6485dadaf75052a00079fc772d9e->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/block/block--views-block--articles--main-articles-page.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('block', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 117) __TwigTemplate_b3fe52432436677338dad3d61809f538->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/layout/page.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('page', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 86) __TwigTemplate_8fe1b8668882dc7655cca60ecfc7b958->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/layout/html.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('html', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 158) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\{closure}() (Line: 592) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->executeInRenderContext(Object, Object) (Line: 159) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->renderResponse(Array, Object, Object) (Line: 90) Drupal\Core\EventSubscriber\MainContentViewSubscriber->onViewRenderArray(Object, 'kernel.view', Object) call_user_func(Array, Object, 'kernel.view', Object) (Line: 111) Drupal\Component\EventDispatcher\ContainerAwareEventDispatcher->dispatch(Object, 'kernel.view') (Line: 186) Symfony\Component\HttpKernel\HttpKernel->handleRaw(Object, 1) (Line: 76) Symfony\Component\HttpKernel\HttpKernel->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 58) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\Session->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 48) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\KernelPreHandle->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 191) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->fetch(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 128) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->lookup(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 82) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 270) Drupal\shield\ShieldMiddleware->bypass(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 137) Drupal\shield\ShieldMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 48) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\ReverseProxyMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 51) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\NegotiationMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 51) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\StackedHttpKernel->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 704) Drupal\Core\DrupalKernel->handle(Object) (Line: 19) - Warning: Undefined array key 0 in Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances() (line 389 of modules/contrib/footnotes/src/Plugin/Filter/FootnotesFilter.php).

Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances('Agrippina the Younger watches as men of the emperor move nearer and nearer to her. They carry weapons. Having survived one attempt on her life, she knows that she will not survive another. One man knocks her over the head with a club and another raises his sword. With her last breath, she implores her killers to strike through her womb— the womb that birthed Nero, her matricidal son. <em>The Remorse of Nero After Killing his Mother</em> by John William Waterhouse Public domain, source: http://www.wikiart.org/en/john-william-waterhouse/the-remorse-of-nero-after-the- murder-of-his-mother-1878, in which Nero realizes that maybe killing his mother 1 wasn’t a nice thing to do. Image courtesy of The Victorian Web This account of Agrippina’s death, corroborated by several ancient historians but likelyC.f., Tacitus 14; Dio 12.12-14. embellished, previews the difficulties we will face in exploring Agrippina in the historical record. Why does Agrippina asked to be stabbed through the womb? Yes, she birthed Nero, but could her last plea also represent a Lady Macbeth-esque desire to unsex herself—a metonymic exhortation to destroy that which made her a woman? Is this question of any import to her portrait at the RISD Museum? Turning first to how contemporary revisionist historians have begun to view earlier historians of Agrippina, I will then look at the role of Agrippina’s portrait as a living cultural artifact inextricably linked with certain changes in the historical reception of Agrippina. Agrippina the Younger (15–59 CE) was closely connected to the first five Roman emperors: she was great-granddaughter of Augustus, great-niece and adoptive granddaughter of Tiberius, sister of Caligula, niece and fourth wife of Claudius, and mother of Nero. Beyond her noble status, Agrippina demanded “real and official power” and not mere “influence.” That Agrippina faces a hostile historical record isImperial Women 259. beyond debate and related to her demands for this sort of power. Since Suetonius andIbid; I, Claudia 62. Tacitus, she has been characterized as bloodthirsty, overly ambitious, sexually flagrant, and unfeminine; and accused of crimes from murder to incest.Imperial Women, 1. Susan Wood, who has written much on Agrippina the Younger and other Roman women, traces this hostile historical record, above all else, to Agrippina’s encroachment on traditionally male privileges, and colorfully points to prejudices and inaccuracies in many of the accusations against her. I would like to focus first on Wood’s assertionImperial Women 259. that the frequency that powerful and intelligent woman faced nearly identical accusations renders them suspect. Such depictions of these women, which still abound in AmericanImperial Women 262 politics today, stem from actual misogyny or a desire to use a stereotype as an easy rhetorical shortcut. Second, Wood holds that the structure of Roman society encouraged its women to act indirectly. Direct avenues of holding power were closed off to women and thus, if they wanted to exercise power, they were forced to pursue “devious and manipulative forms of behavior.” While not exonerating Agrippina from all blame— even the most revisionist of historians agree that she was still guilty of many crimes— we should look critically on accusations against her, in particular those that follow a predictable pattern. Understanding Agrippina’s legacy in the contemporary historical debate prepares us to more fully appreciate the RISD Museum's portrait of Agrippina, its role (or roles) in this muddled historical record, and what it means to the viewer today. Since the move away from more realistic representations under Augustus, Roman portraiture began to be used as a tool for communicating ideologies.www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ropo2/hd_ropo2.htm What sort of ideology does Agrippina’s portrait communicate? First of all, we must ask who commissioned the statue, and thus who was doing the communicating. We can’t be sure that Agrippina commissioned the statue, or when in her life it would have been commissioned. Museum records date the piece to circa 40 CE. If dated before Caligula’s death, it could have been commissioned by Caligula himself. In this case, the statue would have acted as part of Caligula’s plan to elevate Agrippina, Drusilla, and his other sisters.. Through this Cult of Drusilla, Caligula sought to set up his sisters as objects of veneration in order to cement his own rule and power.Barrett 225; “Diva Drusilla Panthea and the Sisters of Caligula”. They were invoked with Caligula in public oaths and, together with Antonia the Younger, were the first to be granted privileges normally accorded to the Vestal Virgins.Behen 62 We can see an example of such a depiction on the backside of the coin belowBarret 225; Source of image: http://www.wildwinds.com/coins/sear5/s1800.html: <a href="https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Caligula_sestertius_RIC_33_680999.jpg">Sestertius from rule of Caligula. Front: Germanicus; Back: Agrippina the Younger and her sisters.</a> However, if we suppose that the statue was commissioned by Agrippina, the function is altered and Agrippina is the one in control of manipulating her own image. This portrait and other commissioned by Agrippina can as Curator of Ancient Art Gina Borromeo writes, “give us an idea of how she wished to be portrayed.”Borromeo, “Looking an Empress in the Eye.” Given that Agrippina’ autobiography was destroyed,Borromeo, “Looking an Empress in the Eye.” this piece might be able to grant us invaluable insight into understanding a figure so prejudiced by the historical record, as she herself wished to be perceived. In any case, one should be no less critical here than with the rest of the historical record, and we can only suggest this as one possible interpretation. Presuming that Agrippina commissioned the portrait, it seems unlikely that it was when Agrippina’s power was most threatened. From late 39 to January 41, she was exiled by her brother Caligula. It might be the case that this statue was a part of an effort by Agrippina to reconsolidate her power upon returning from exile. It is interesting to entertain the idea that this might be from a year as late as 49 — after she married Claudius and become empress but that seems unlikely, as other statues we have from that period display evidence of an imperial diadem.Behen 63. The idea that Agrippina commissioned the portrait can be supported with close inspection. The portrait seems to depart from the faceless, unassuming Vestal Virgin of the sestertius minted under Caligula. She does not ask us to idealize her as some feminine standard of beauty; rather, she presents herself as “rather jowly” with “heavy features” and a “large nose,”Barrett 225. and there is a “certain asymmetry in her features” and especially the nose.Ridgway 201. This could be a response to gossip that circulated against her, as a woman and of which she might have had some awareness. As contemporary biographer Anthony A. Barrett observes, her attractiveness is not a “trivial issue” when historians such as Tacitus claimed that she was a “beautiful woman” who used her “physical charms to ensnare a defenseless Claudius, among others.”Barrett 225. Agrippina looks determined, fearless, and perhaps even disdainful. The severe eyebrows extend horizontally to the hairline and dislocate the forehead, and elevate the corner of the brows in a way that lend force to this expression.Ridgway 201. Running parallel from a center part, the tresses of hair becomes tighter as it moves towards the ears.Ibid. This style possibly evokes, as it does in other portraits of her,Behen 63. that of Agrippina’s mother who was also politically powerful and suffered exile. The allusion to her mother’s hairstyle would have presumably been more apparent to those who lived in Rome who grew up around representations of Agrippina the Elder. In drawing comparison to her mother, Agrippina the Younger insists on her noble lineage and right to wield authority, even as a woman; she anticipates the future power that she would one day hold and had pretensions of holding and legitimizes her right to that power by invocation. Similarly her protruding upper lip and small chin recall depictions of her brother Caligula, Behen 62. and these resemblances seek to further highlight her dynastic right to rule. The bust of the statue—including the taupe tunic, green mantle, and socle (or simple pedestal)—is not ancient but likely from the 18th century and parallels other portraits we have from this era.Borromeo, “Looking an Empress in the Eye.” In addition to this theory, this article also contains a more detailed treatment of the 18th century additions. What does the addition say about 18th century tastes and perceptions of this portrait, and the larger question of how historical forces can shape perceptions of an object? To begin to answer these questions, one must first understand 18th century restoration practices. Often broken statutes were mended with new creations (for another example, the RISD Museum’s <em>Figure in the Guise of Hermes</em>; both the ancient body and removed leg of 18th century origin can be viewed in the Ancient Art Gallery). The addition of the bust in the case of the Agrippina perhaps was responding to a need to more easily display the piece and a perceived lack of color. The RISD Museum acquired the piece from a Marchioness of Linlithgow and before that it was probably proudly exhibited by many other wealthy individuals. Here these individuals used this piece in a similar manner to how we guessed Agrippina might have—to highlight nobility and power. These perceived deficiencies unawarely hit on the part that the portrait played in antiquity. As Borromeo elucidates, ancient statues of white marble were typically painted in vivid colors, thus this 18th century addition incidentally gives the contemporary museumgoer some indication of the effect that color would have added.Borromeo, “Looking an Empress in the Eye.” While this proves to be an interesting historical coincidence, one would err to imagine that this negates the history of this object and reverts it to some earlier form; rather, these additions present a visual manifestation of how viewers of different periods can bring something of their own age to a work, so as to inscribe new meaning and shed light on aspects that have long laid dormant. As the literary critic and theorist Stephen Greenblatt states, “Cultural artifacts do not stay still, . . . they exist in time, and . . . they are bound up with personal and institutional conflicts, negotiations, and appropriations.” One would be remiss to see Agrippina’s portrait at the RISD Museum and assume its significance was locked up in Imperial Rome. Commenting on the legacy of Agrippina, Barrett questions whether she was ever able to escape a “devastating ‘image’ problem.”Barrett 225. Like Wood, he views her manipulation as necessary—although not excusable—in the misogynistic culture that she faced. Successful manipulation was not only a matter of publicity but also of life and death. She excelled in this manipulation as the wife of Claudius but “tragically failed” as the life of Nero, leading to the death described at the beginning of this essay. In her own time, Barrett concludes, “She did not change the hardened attitude of her contemporaries, but she did define what Romans were willing to tolerate.” In a similar way, her portrait measures what the people of various ages are willing to tolerate, and mirrors and even influences social and cultural processes. The recent revisionist work of historians such as Wood and Barrett opens up to us new hermeneutic possibilities that reflect larger developments and processes of our times. On the other hand, we should avoid presenting our own age as superior. As media coverage of the 2016 American presidential election reminds us, it is all too easy to let misleading tropes color perception. Although it cannot be said that, when it comes to attitudes about women, American society is fully beyond the hardened attitudes of Imperial Rome, examining how other ages received Agrippina and her portrait can alert us to systemic flaws in our own thought processes. Bibliography Behen, Michael J., in Diana Kleiner and Susan Matheson, eds. I Claudia: Women in Ancient Rome (New Haven, 1996), 62-63. Barrett, Anthony. Agrippina. Florence, US: Routledge, 2002. ProQuest ebrary. Web. 15 May 2016. Borromeo, Gina. “Looking an Empress in the Eye,” RISD Museum Manual. Web. May 2016 Clark, A. M., “An Agrippina,” Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design, Museum Notes 44 (May 1958) 3–5, 10. Ridgway, Brunilde S., Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Classical Sculpture (Providence, 1972) 86–87, 201–204. Trentinella, Rosemarie. “Roman Portrait Sculpture: The Stylistic Cycle.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. www.metmuseum.org/toah/ hd/ropo2/hd_ropo2.htm (October 2003) Wood, Susan E., “Diva Drusilla Panthea and the Sisters of Caligula,” American Journal of Archaeology 99 (1995): 457–82. Wood, Susan E., Imperial Women: A Study in Public Images, 40 BC–AD 68 (Boston, 1999), with earlier references. ') (Line: 116) Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->process('Agrippina the Younger watches as men of the emperor move nearer and nearer to her. They carry weapons. Having survived one attempt on her life, she knows that she will not survive another. One man knocks her over the head with a club and another raises his sword. With her last breath, she implores her killers to strike through her womb— the womb that birthed Nero, her matricidal son. <em>The Remorse of Nero After Killing his Mother</em> by John William Waterhouse Public domain, source: http://www.wikiart.org/en/john-william-waterhouse/the-remorse-of-nero-after-the- murder-of-his-mother-1878, in which Nero realizes that maybe killing his mother 1 wasn’t a nice thing to do. Image courtesy of The Victorian Web This account of Agrippina’s death, corroborated by several ancient historians but likelyC.f., Tacitus 14; Dio 12.12-14. embellished, previews the difficulties we will face in exploring Agrippina in the historical record. Why does Agrippina asked to be stabbed through the womb? Yes, she birthed Nero, but could her last plea also represent a Lady Macbeth-esque desire to unsex herself—a metonymic exhortation to destroy that which made her a woman? Is this question of any import to her portrait at the RISD Museum? Turning first to how contemporary revisionist historians have begun to view earlier historians of Agrippina, I will then look at the role of Agrippina’s portrait as a living cultural artifact inextricably linked with certain changes in the historical reception of Agrippina. Agrippina the Younger (15–59 CE) was closely connected to the first five Roman emperors: she was great-granddaughter of Augustus, great-niece and adoptive granddaughter of Tiberius, sister of Caligula, niece and fourth wife of Claudius, and mother of Nero. Beyond her noble status, Agrippina demanded “real and official power” and not mere “influence.” That Agrippina faces a hostile historical record isImperial Women 259. beyond debate and related to her demands for this sort of power. Since Suetonius andIbid; I, Claudia 62. Tacitus, she has been characterized as bloodthirsty, overly ambitious, sexually flagrant, and unfeminine; and accused of crimes from murder to incest.Imperial Women, 1. Susan Wood, who has written much on Agrippina the Younger and other Roman women, traces this hostile historical record, above all else, to Agrippina’s encroachment on traditionally male privileges, and colorfully points to prejudices and inaccuracies in many of the accusations against her. I would like to focus first on Wood’s assertionImperial Women 259. that the frequency that powerful and intelligent woman faced nearly identical accusations renders them suspect. Such depictions of these women, which still abound in AmericanImperial Women 262 politics today, stem from actual misogyny or a desire to use a stereotype as an easy rhetorical shortcut. Second, Wood holds that the structure of Roman society encouraged its women to act indirectly. Direct avenues of holding power were closed off to women and thus, if they wanted to exercise power, they were forced to pursue “devious and manipulative forms of behavior.” While not exonerating Agrippina from all blame— even the most revisionist of historians agree that she was still guilty of many crimes— we should look critically on accusations against her, in particular those that follow a predictable pattern. Understanding Agrippina’s legacy in the contemporary historical debate prepares us to more fully appreciate the RISD Museum's portrait of Agrippina, its role (or roles) in this muddled historical record, and what it means to the viewer today. Since the move away from more realistic representations under Augustus, Roman portraiture began to be used as a tool for communicating ideologies.www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ropo2/hd_ropo2.htm What sort of ideology does Agrippina’s portrait communicate? First of all, we must ask who commissioned the statue, and thus who was doing the communicating. We can’t be sure that Agrippina commissioned the statue, or when in her life it would have been commissioned. Museum records date the piece to circa 40 CE. If dated before Caligula’s death, it could have been commissioned by Caligula himself. In this case, the statue would have acted as part of Caligula’s plan to elevate Agrippina, Drusilla, and his other sisters.. Through this Cult of Drusilla, Caligula sought to set up his sisters as objects of veneration in order to cement his own rule and power.Barrett 225; “Diva Drusilla Panthea and the Sisters of Caligula”. They were invoked with Caligula in public oaths and, together with Antonia the Younger, were the first to be granted privileges normally accorded to the Vestal Virgins.Behen 62 We can see an example of such a depiction on the backside of the coin belowBarret 225; Source of image: http://www.wildwinds.com/coins/sear5/s1800.html: <a href="https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Caligula_sestertius_RIC_33_680999.jpg">Sestertius from rule of Caligula. Front: Germanicus; Back: Agrippina the Younger and her sisters.</a> However, if we suppose that the statue was commissioned by Agrippina, the function is altered and Agrippina is the one in control of manipulating her own image. This portrait and other commissioned by Agrippina can as Curator of Ancient Art Gina Borromeo writes, “give us an idea of how she wished to be portrayed.”Borromeo, “Looking an Empress in the Eye.” Given that Agrippina’ autobiography was destroyed,Borromeo, “Looking an Empress in the Eye.” this piece might be able to grant us invaluable insight into understanding a figure so prejudiced by the historical record, as she herself wished to be perceived. In any case, one should be no less critical here than with the rest of the historical record, and we can only suggest this as one possible interpretation. Presuming that Agrippina commissioned the portrait, it seems unlikely that it was when Agrippina’s power was most threatened. From late 39 to January 41, she was exiled by her brother Caligula. It might be the case that this statue was a part of an effort by Agrippina to reconsolidate her power upon returning from exile. It is interesting to entertain the idea that this might be from a year as late as 49 — after she married Claudius and become empress but that seems unlikely, as other statues we have from that period display evidence of an imperial diadem.Behen 63. The idea that Agrippina commissioned the portrait can be supported with close inspection. The portrait seems to depart from the faceless, unassuming Vestal Virgin of the sestertius minted under Caligula. She does not ask us to idealize her as some feminine standard of beauty; rather, she presents herself as “rather jowly” with “heavy features” and a “large nose,”Barrett 225. and there is a “certain asymmetry in her features” and especially the nose.Ridgway 201. This could be a response to gossip that circulated against her, as a woman and of which she might have had some awareness. As contemporary biographer Anthony A. Barrett observes, her attractiveness is not a “trivial issue” when historians such as Tacitus claimed that she was a “beautiful woman” who used her “physical charms to ensnare a defenseless Claudius, among others.”Barrett 225. Agrippina looks determined, fearless, and perhaps even disdainful. The severe eyebrows extend horizontally to the hairline and dislocate the forehead, and elevate the corner of the brows in a way that lend force to this expression.Ridgway 201. Running parallel from a center part, the tresses of hair becomes tighter as it moves towards the ears.Ibid. This style possibly evokes, as it does in other portraits of her,Behen 63. that of Agrippina’s mother who was also politically powerful and suffered exile. The allusion to her mother’s hairstyle would have presumably been more apparent to those who lived in Rome who grew up around representations of Agrippina the Elder. In drawing comparison to her mother, Agrippina the Younger insists on her noble lineage and right to wield authority, even as a woman; she anticipates the future power that she would one day hold and had pretensions of holding and legitimizes her right to that power by invocation. Similarly her protruding upper lip and small chin recall depictions of her brother Caligula, Behen 62. and these resemblances seek to further highlight her dynastic right to rule. The bust of the statue—including the taupe tunic, green mantle, and socle (or simple pedestal)—is not ancient but likely from the 18th century and parallels other portraits we have from this era.Borromeo, “Looking an Empress in the Eye.” In addition to this theory, this article also contains a more detailed treatment of the 18th century additions. What does the addition say about 18th century tastes and perceptions of this portrait, and the larger question of how historical forces can shape perceptions of an object? To begin to answer these questions, one must first understand 18th century restoration practices. Often broken statutes were mended with new creations (for another example, the RISD Museum’s <em>Figure in the Guise of Hermes</em>; both the ancient body and removed leg of 18th century origin can be viewed in the Ancient Art Gallery). The addition of the bust in the case of the Agrippina perhaps was responding to a need to more easily display the piece and a perceived lack of color. The RISD Museum acquired the piece from a Marchioness of Linlithgow and before that it was probably proudly exhibited by many other wealthy individuals. Here these individuals used this piece in a similar manner to how we guessed Agrippina might have—to highlight nobility and power. These perceived deficiencies unawarely hit on the part that the portrait played in antiquity. As Borromeo elucidates, ancient statues of white marble were typically painted in vivid colors, thus this 18th century addition incidentally gives the contemporary museumgoer some indication of the effect that color would have added.Borromeo, “Looking an Empress in the Eye.” While this proves to be an interesting historical coincidence, one would err to imagine that this negates the history of this object and reverts it to some earlier form; rather, these additions present a visual manifestation of how viewers of different periods can bring something of their own age to a work, so as to inscribe new meaning and shed light on aspects that have long laid dormant. As the literary critic and theorist Stephen Greenblatt states, “Cultural artifacts do not stay still, . . . they exist in time, and . . . they are bound up with personal and institutional conflicts, negotiations, and appropriations.” One would be remiss to see Agrippina’s portrait at the RISD Museum and assume its significance was locked up in Imperial Rome. Commenting on the legacy of Agrippina, Barrett questions whether she was ever able to escape a “devastating ‘image’ problem.”Barrett 225. Like Wood, he views her manipulation as necessary—although not excusable—in the misogynistic culture that she faced. Successful manipulation was not only a matter of publicity but also of life and death. She excelled in this manipulation as the wife of Claudius but “tragically failed” as the life of Nero, leading to the death described at the beginning of this essay. In her own time, Barrett concludes, “She did not change the hardened attitude of her contemporaries, but she did define what Romans were willing to tolerate.” In a similar way, her portrait measures what the people of various ages are willing to tolerate, and mirrors and even influences social and cultural processes. The recent revisionist work of historians such as Wood and Barrett opens up to us new hermeneutic possibilities that reflect larger developments and processes of our times. On the other hand, we should avoid presenting our own age as superior. As media coverage of the 2016 American presidential election reminds us, it is all too easy to let misleading tropes color perception. Although it cannot be said that, when it comes to attitudes about women, American society is fully beyond the hardened attitudes of Imperial Rome, examining how other ages received Agrippina and her portrait can alert us to systemic flaws in our own thought processes. Bibliography Behen, Michael J., in Diana Kleiner and Susan Matheson, eds. I Claudia: Women in Ancient Rome (New Haven, 1996), 62-63. Barrett, Anthony. Agrippina. Florence, US: Routledge, 2002. ProQuest ebrary. Web. 15 May 2016. Borromeo, Gina. “Looking an Empress in the Eye,” RISD Museum Manual. Web. May 2016 Clark, A. M., “An Agrippina,” Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design, Museum Notes 44 (May 1958) 3–5, 10. Ridgway, Brunilde S., Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Classical Sculpture (Providence, 1972) 86–87, 201–204. Trentinella, Rosemarie. “Roman Portrait Sculpture: The Stylistic Cycle.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. www.metmuseum.org/toah/ hd/ropo2/hd_ropo2.htm (October 2003) Wood, Susan E., “Diva Drusilla Panthea and the Sisters of Caligula,” American Journal of Archaeology 99 (1995): 457–82. Wood, Susan E., Imperial Women: A Study in Public Images, 40 BC–AD 68 (Boston, 1999), with earlier references. ', 'en') (Line: 118) Drupal\filter\Element\ProcessedText::preRenderText(Array) call_user_func_array(Array, Array) (Line: 111) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doTrustedCallback(Array, Array, 'Render #pre_render callbacks must be methods of a class that implements \Drupal\Core\Security\TrustedCallbackInterface or be an anonymous function. The callback was %s. See https://www.drupal.org/node/2966725', 'exception', 'Drupal\Core\Render\Element\RenderCallbackInterface') (Line: 797) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doCallback('#pre_render', Array, Array) (Line: 386) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 106) __TwigTemplate_4039b6d648e4a30fc59604b38849a688->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 46) __TwigTemplate_d1494d795b4bd5366283e85f3e7729dc->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 43) __TwigTemplate_253b62141ad73ee07345b0067cf59829->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/contrib/classy/templates/field/field--text-with-summary.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('field', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 231) __TwigTemplate_d0a4e06ec4cdc862487a9e59e7ee55e6->block_node_content(Array, Array) (Line: 171) Twig\Template->displayBlock('node_content', Array, Array) (Line: 91) __TwigTemplate_fb45c12c057c90d6dad87acc3f8af627->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 51) __TwigTemplate_d0a4e06ec4cdc862487a9e59e7ee55e6->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/content/node--teaser.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('node', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 60) __TwigTemplate_b5820ae2fc9ac809d8bb920432eaa798->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/contrib/classy/templates/views/views-view-unformatted.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('views_view_unformatted', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 110) __TwigTemplate_fc3dc095246a9d6d2c8632ac77f62c14->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/contrib/classy/templates/views/views-view.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('views_view', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 74) __TwigTemplate_c81e6485dadaf75052a00079fc772d9e->block_content(Array, Array) (Line: 171) Twig\Template->displayBlock('content', Array, Array) (Line: 62) __TwigTemplate_c81e6485dadaf75052a00079fc772d9e->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/block/block--views-block--articles--main-articles-page.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('block', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 117) __TwigTemplate_b3fe52432436677338dad3d61809f538->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/layout/page.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('page', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 86) __TwigTemplate_8fe1b8668882dc7655cca60ecfc7b958->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/layout/html.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('html', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 158) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\{closure}() (Line: 592) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->executeInRenderContext(Object, Object) (Line: 159) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->renderResponse(Array, Object, Object) (Line: 90) Drupal\Core\EventSubscriber\MainContentViewSubscriber->onViewRenderArray(Object, 'kernel.view', Object) call_user_func(Array, Object, 'kernel.view', Object) (Line: 111) Drupal\Component\EventDispatcher\ContainerAwareEventDispatcher->dispatch(Object, 'kernel.view') (Line: 186) Symfony\Component\HttpKernel\HttpKernel->handleRaw(Object, 1) (Line: 76) Symfony\Component\HttpKernel\HttpKernel->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 58) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\Session->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 48) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\KernelPreHandle->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 191) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->fetch(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 128) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->lookup(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 82) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 270) Drupal\shield\ShieldMiddleware->bypass(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 137) Drupal\shield\ShieldMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 48) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\ReverseProxyMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 51) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\NegotiationMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 51) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\StackedHttpKernel->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 704) Drupal\Core\DrupalKernel->handle(Object) (Line: 19) - Warning: Undefined array key 0 in Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances() (line 388 of modules/contrib/footnotes/src/Plugin/Filter/FootnotesFilter.php).