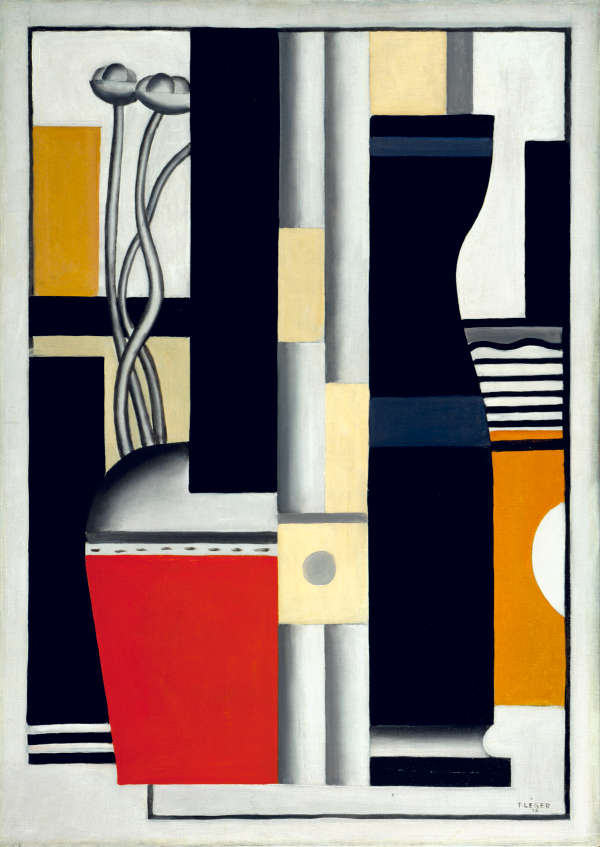

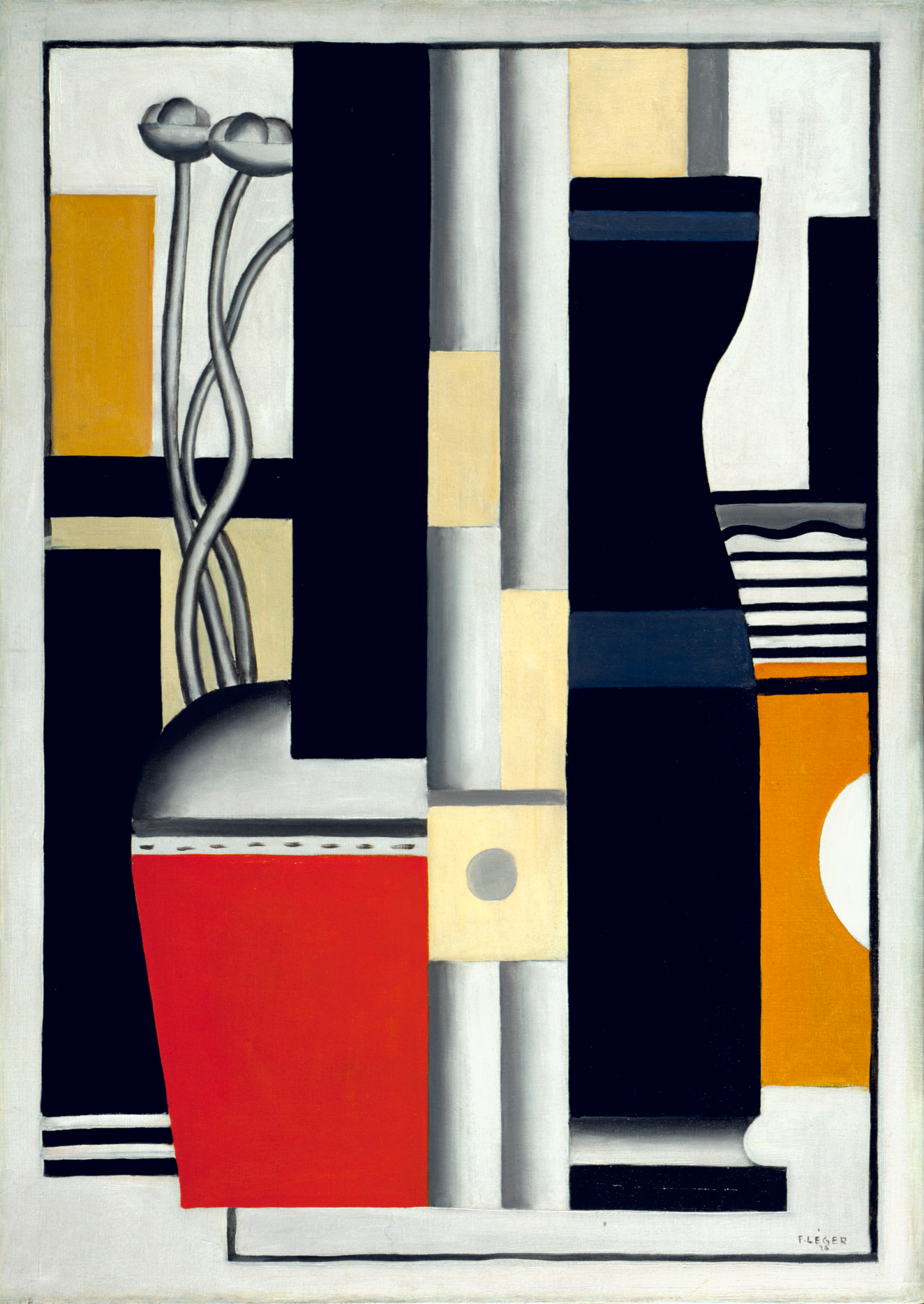

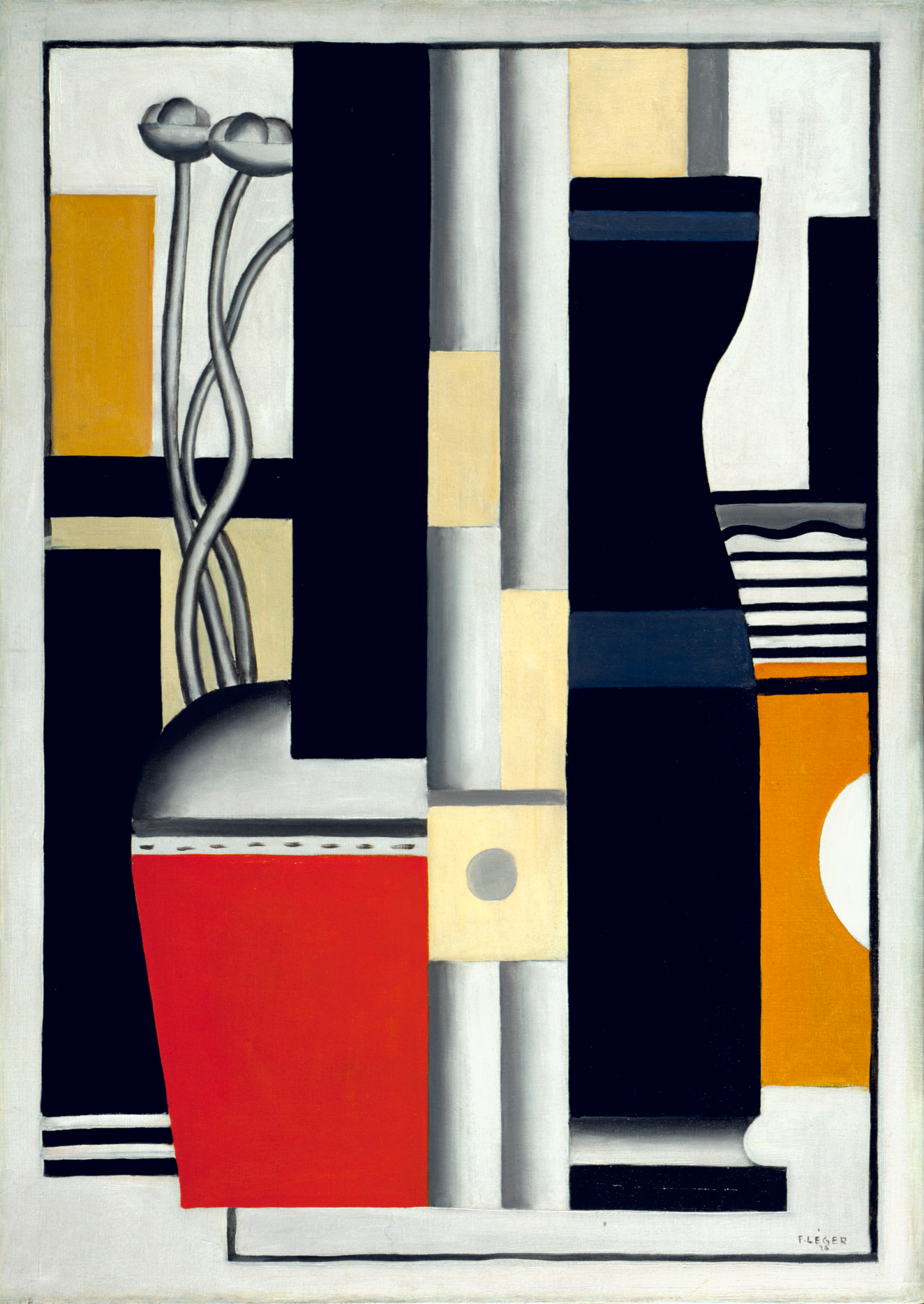

Better Still

Introduction

The “still life” has a long tradition in the history of art. Images of sumptuous containers filled with flowers, fruits, and vegetables reached a high point in the Netherlands in the 17th century, but their origins date back to the wall paintings of ancient Greece and Rome. The types of familiar domestic objects usually presented have changed little over time, permitting a continuity of appreciation over many generations. The viewer feels an immediate connection to basic household interiors, the necessities of eating and drinking, and the artifacts that surround the daily routines of kitchen, dining room, table, and market.

Still-life painting was long considered the lowest category of picture-making, distanced from the momentous events and moral implications of history painting or formal portraiture. Even so, patrons have always enjoyed its ability to convey wealth and social status. Rare tulip blooms, decorative objects, and small exotic animals have been represented with great skill over the years, as have the fur and feathers of the hunt’s bounty. From a salute to class privilege, humbler visions emerged: a simple breakfast of bread and eggs that might grace the rough table of a country home; a coffee cup and newspaper, representing life in an urban apartment. Compositions also may include references to the passage of time and to nature’s cycles of life, death, decay, and transformation.

In the artist’s studio, the usefulness and appeal of the still-life composition has never diminished. In the 20th century its possibilities expanded to include modernist collage, surrealist constructions, and room-size installations. Artists continue to find willing models in the inanimate objects around them. Their configurations suggest domestic dramas, moments of clarity, and memories of the past that provoke and delight.

Maureen O'Brien