Bodies of Evidence

Introduction

This exhibition grew out of a desire to highlight work by women of color from The RISD Museum’s collection and to display the many recent acquisitions in this area. After surveying the holdings, it was determined that the most cohesive presentation could be assembled from art created since 1960 and focused thematically on the body. The exhibition’s title also refers to the show as a testimony to the creative vitality of women of color, a group whose work has increasingly been recognized internationally as an invigorating presence.

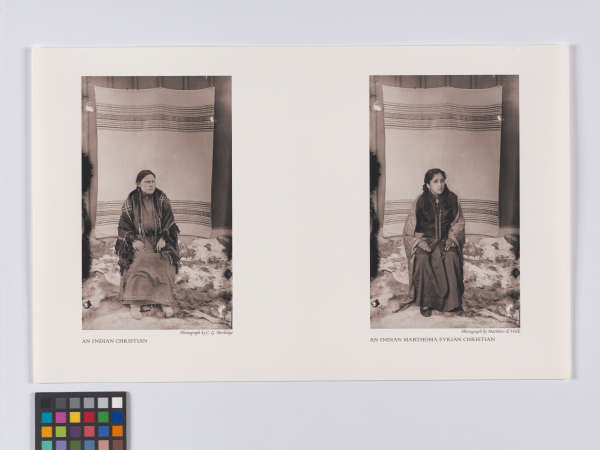

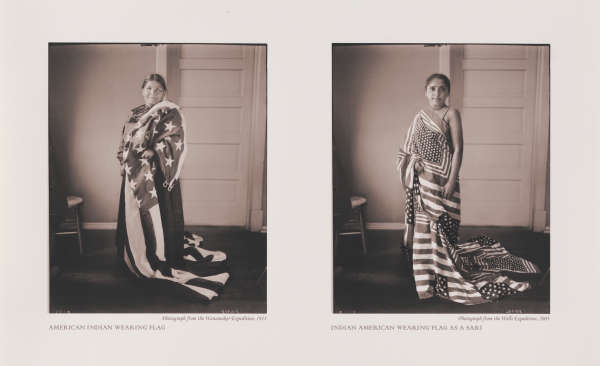

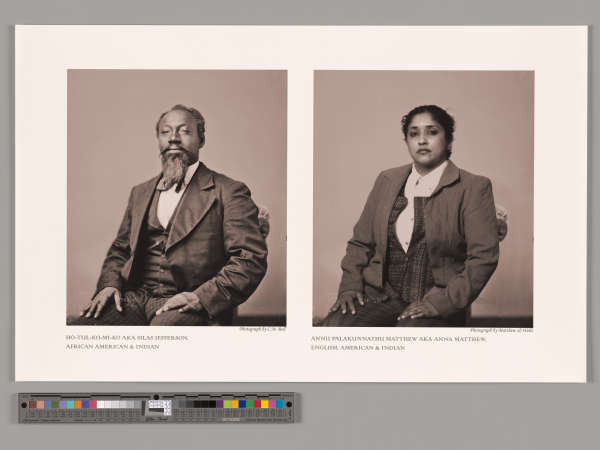

In many examples the artists use their own bodies as poignant agents of expression. Marta María Pérez Bravo photographs herself in staged ritualistic performances referencing Cuban Santería and Palo Monte religions. Renée Stout alludes to the Haitian voodoo deity Erzulie as she poses in a photographic narrative of unrequited love. Annu Palakunnathu Matthew mimics the stance of Native Americans portrayed in late-19th and early 20th-century photographs to expose constructions of “otherness” and compares these historical portrayals to those of her East Indian cultural birthright. Conceptual artist and philosopher Adrian Piper documents her existence over the course of a summer in response to a metaphysical text that led her to question her own physical embodiment. Her nearly impenetrable photographs are analogous to the challenges of understanding people simply by looking at their exteriors. In many images she is naked, metaphorically stripped to her core being, and by so presenting herself in both her intellectual and physical essence, she confronts innumerable gender issues as well. In her video, performance artist Patty Chang presents the unpleasant and intimate act of consuming an onion, which is passed back and forth between her mouth and the most unexpected partners in a stark portrayal of the physical and emotional bonds of family.

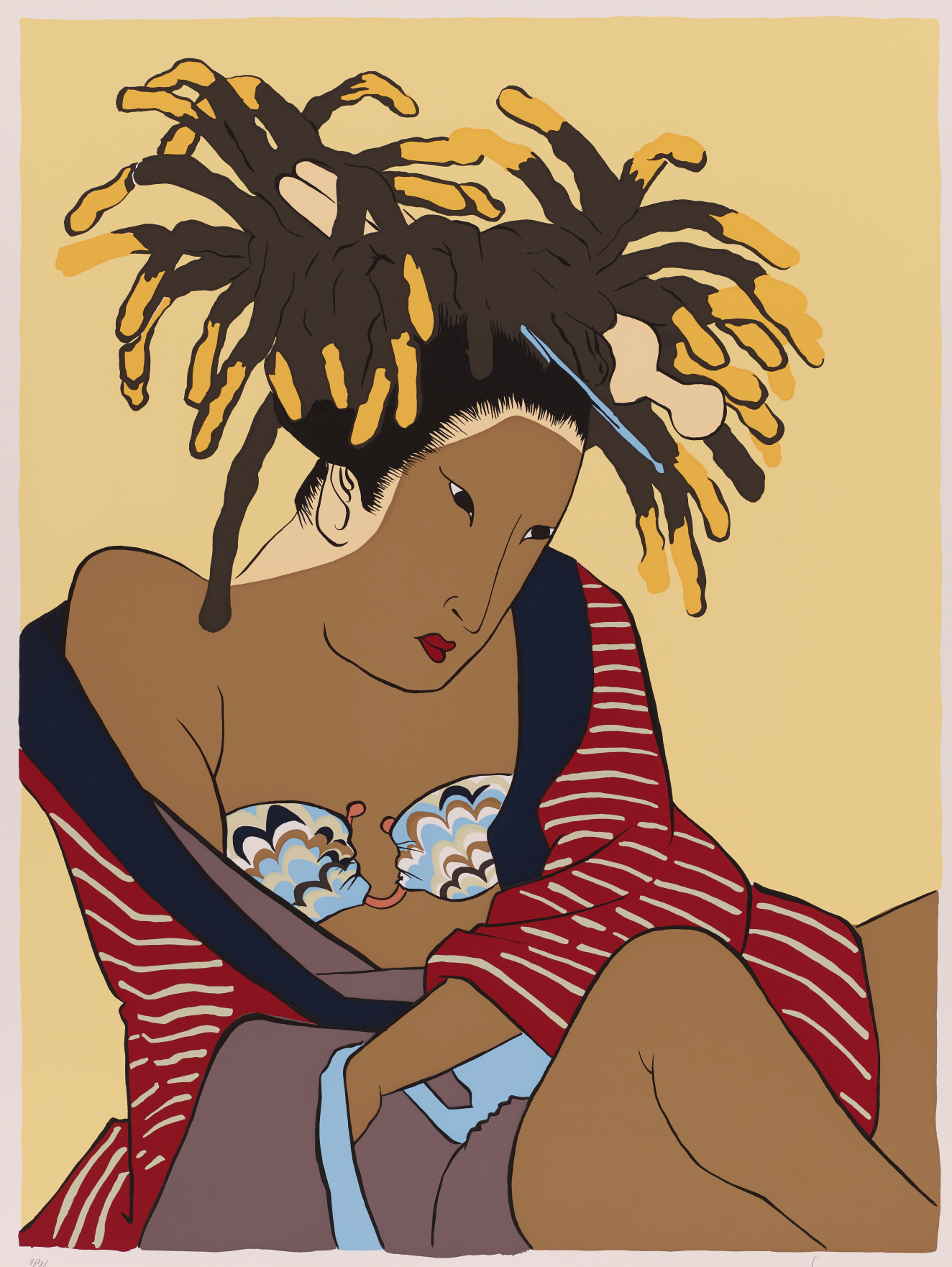

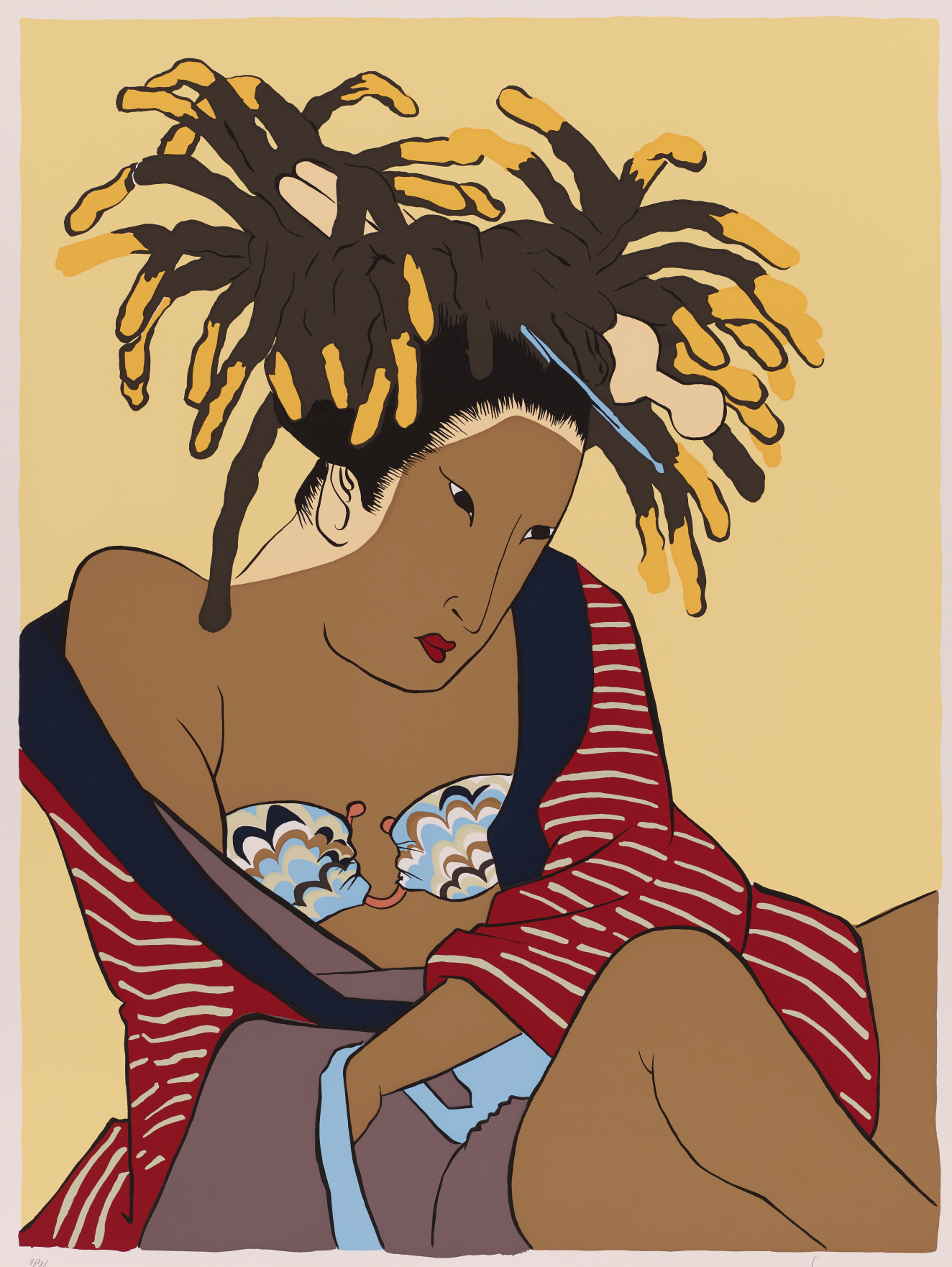

Iona Rozeal Brown and Kara Walker use stylized representations of the figure to comment on social issues. Brown draws upon the tradition of late-18th-century Japanese woodblock prints to portray the contemporary phenomenon of ganguro - Japanese youths who mimic hip-hop audio artists by darkening their skin and coiling their hair into dreadlocks. Like Brown, Walker appropriates an historical genre to depict her characters. Using the familiar 19th-century silhouette, she relates explosive visual narratives that reveal unspoken truths of racial and sexual taboos. By embedding charged imagery within the polite tradition of the silhouette, she greatly enhances the potent and seductive power of her art.

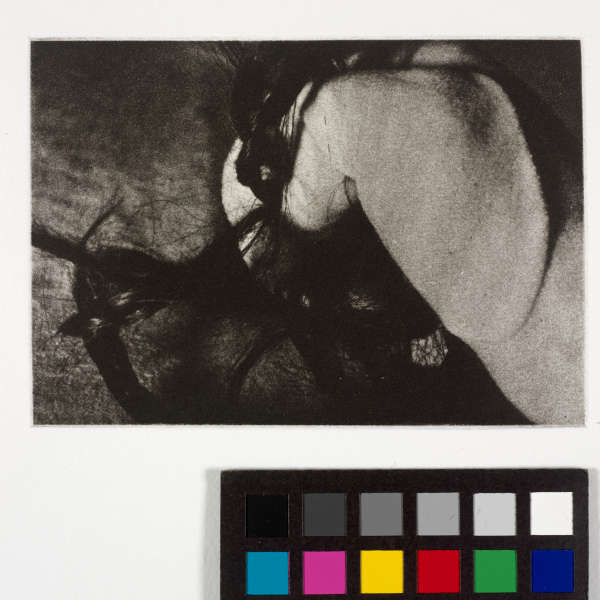

Alison Saar, Lorna Simpson, Joyce Scott, and Ana Mendieta work with generalized representations to speak to historical and cultural concerns. Saar’s striking woodcut Ulysses appropriates a classic Greek myth to transpose the theme of resistance and perseverance into an African-American context. Her powerful clothed male figure, hanging from his feet, conjures images of lynching and defenselessness, yet his calm composure defies his situation and his oppressors. Lorna Simpson’s photographic print Counting gives the viewer quite limited information - a Black woman seen from behind, a smoke house and slave quarter, and a coil of braids along with numerical references to time and counting - that nonetheless conjures the plight of African Americans past and present. Critics have noted that Simpson’s coded visual language is consistent with the tradition of African-American musical forms, among them spirituals and blues. Joyce Scott’s dazzling and mysterious beaded sculpture Spirit Siamese Twins mixes references to many cultures as she literally threads symbolic imagery into her female figure. The twins in the piece are Mexican wooden skeletons used in Day of the Dead celebrations, but the reference garners rich meaning from contexts for double births embedded within all cultures. The skeleton, a common image in her work, appears again the monoprint, wherein she addresses the vulnerability of children. Ana Mendieta, too, borrows freely from many cultures. An influential performance and earthwork artist, she created Furrows in 1984 during an artist residency at RISD. Formerly installed in the space where the Museum’s Farago Wing now stands, Furrows outlined the shape of an earth goddess in one ton of sod. Drawing inspiration from ancient cultures that she believed to possess knowledge of and respect for nature, her work points to the association of the female gender with the fecund earth.

Milagros de la Torre and Raquel Paiewonsky use objects as stand-ins for human bodies. De la Torre presents feminine accoutrements - a dress, stockings, a hanger and shoes - in a series of photogravures printed in the negative on delicate paper. Her treatment suggests that these are the ghostly remnants of a fragile life. Paiewonsky’s “dress,” entitled Parida (Birthed), is made up of small plastic and rubber baby dolls, a far larger number of which are white- rather than brown-skinned, reflecting the variety of dolls available for purchase in Santo Domingo. The piece comments on deep-seated prejudices within Dominican culture.

Carrie Mae Weems and Howardena Pindell reference the body in more abstract ways. Weems’s A Place for Him, A Place for Her was inspired by observing male and female references in the architecture of Djenne, Mali, on her first trip to West Africa. In this work she pairs stunning photographs of the Islamic-influenced architecture with her own text, an intermingling of creation myths with her interpretations of the male/female dynamic. Pindell’s drawing of circles and ellipses connected by lines on graph paper, suggests some kind of scientific or measured notation consistent with the work of her minimalist and conceptualist peers. The circle is also associated with a profound childhood memory. While traveling to visit her grandmother in Hamilton, Ohio, her family stopped at a local eatery, where Pindell was served root beer in large glass mug with a prominent red dot on the bottom. Her father explained to her that the dot indicated dishware reserved for serving African-Americans.

In several of the works, memory helps to portray individuals. Donna Bruton (current RISD Faculty), in homage to her father, paints a psychological landscape filled with remembrances of comfort and stability in Me and My Dad. Yamamoto’s Eyes, Dark presents a series of fifteen details of romantic longing in a photographic composition that evokes erotic memories of a girlhood friendship. Milhazes’s artist’s book explodes like a kaleidoscope of forms and colors. The book is a celebration of her relationship with her home, Rio de Janeiro, and in it she responds to the lyrics of twelve traditional and contemporary Brazilian songs that left their mark on her.

Bodies of Evidence: Contemporary Perspectives does not include all women of color represented in the Museum’s collection. The show is a snapshot of RISD’s collection at this moment and highlights its strengths and weaknesses in order to provide direction for continued acquisitions in this area. It is also hoped that the exhibition succeeds in bringing many important artists to the attention of the Southeastern New England community.

Fo Wilson

RISD Graduate Student, Furniture Design, 2005

The exhibition was conceived by James Montford, the Museum’s Coordinator of Community Programs; and co-curated by Fo Wilson and Jan Howard, Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs. We are grateful for the suggestions of our advisory group and those community members who have contributed “Footnote” responses to the works in the exhibition.

Judith Tannenbaum