Celebrating the Jewish Contribution to Twentieth-Century American Art

Introduction

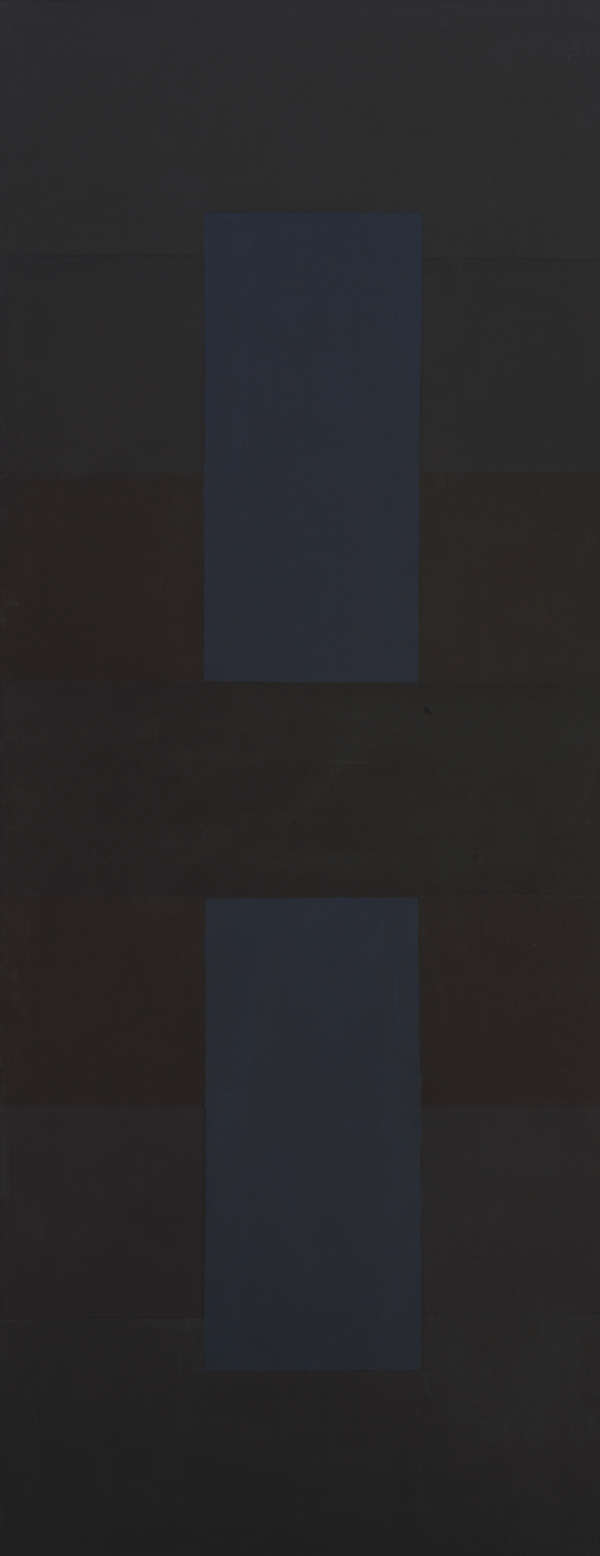

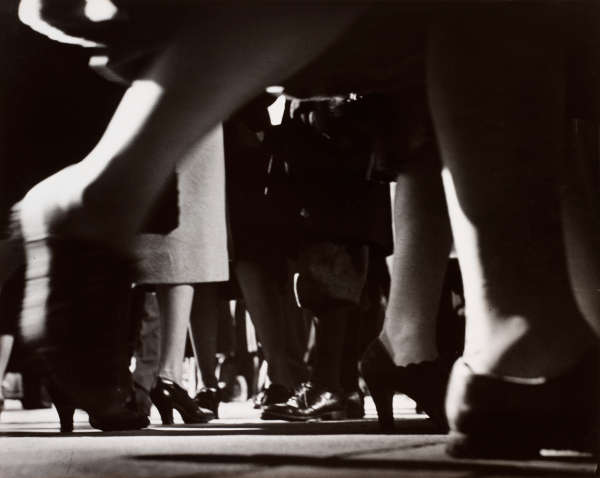

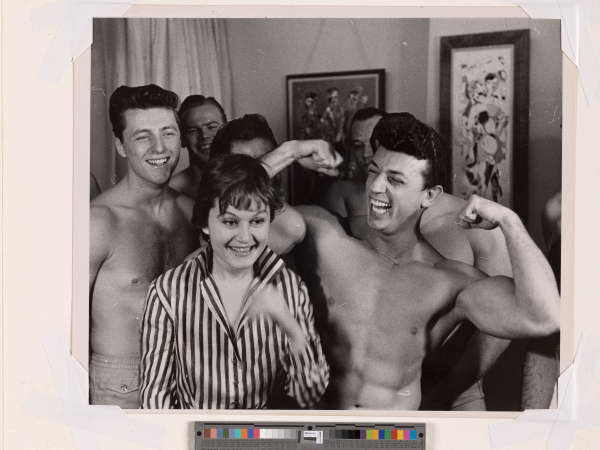

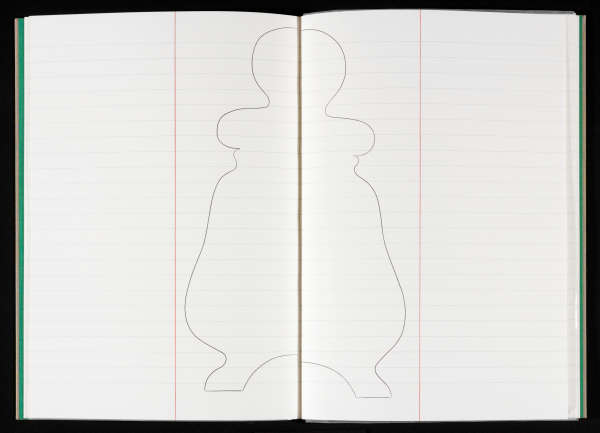

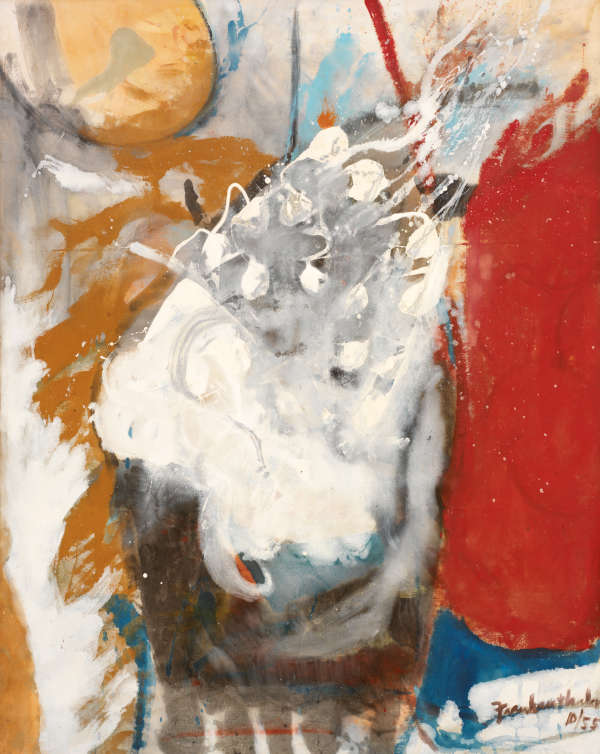

Fifty years ago, The RISD Museum celebrated the 300th anniversary of Jewish life in America. This year we are pleased and proud to recognize the 350th year. The current installation of the permanent collection concentrates on post-1945 American art. This period saw the rise of Abstract Expressionism, a movement that made New York the center of the international art world for the first time. The Museum's holdings are particularly strong for this vital era, which was enriched enormously by the concentration of Jewish artists who participated in the movement's development. Jewish artists also played acentral role in the development of American photography. Many of the photographers represented here are among the most influential of the 20th century.

What circumstances define a "Jewish" artist? Many of the people whose work is on view pointedly refused to define their art as Jewish. Some did not perceive Judaism to be a particularly formative influence; indeed, for artists whose families came to America in the early 20th century, cultural assimilation rather than maintaining a minority identity may well have been a goal. Some felt that their artwork flowed equally from all conditions of their being and experience and that to think of their work as Jewish was limiting. Artists attempting to address the universal human condition may have perceived that a specifically Jewish frame of reference was detrimental to their intent. At various periods, being identified as a member of an ethnic, cultural, or religious minority might also have had a decidedly negative effect on one's career.

At the same time, most of these artists worked and lived within the orbit of the New York art world. Here they had access to an intellectual, socially active, urban Jewish community with leftist leanings, in addition to the larger population of avant-garde artists of other backgrounds who inhabited the city (such as Jackson Pollock, who is included in this exhibition). It is perhaps this situation, more than any religious characteristic of Judaism, that links these artists together in their pursuit of new and often revolutionary modes of expression.

Nathaniel SteinIntern in the Museum's Department of Painting and Sculpture Graduate student in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture, Brown University

Jan Howard