Circus

Introduction

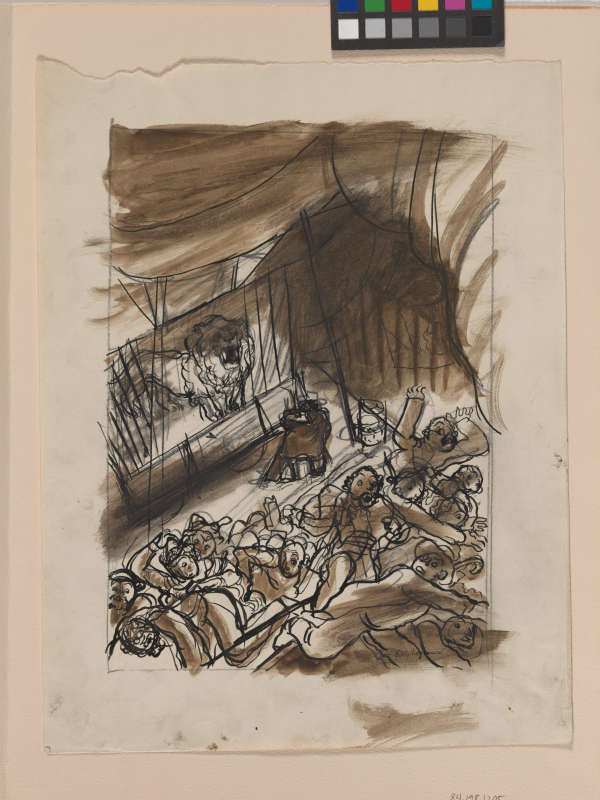

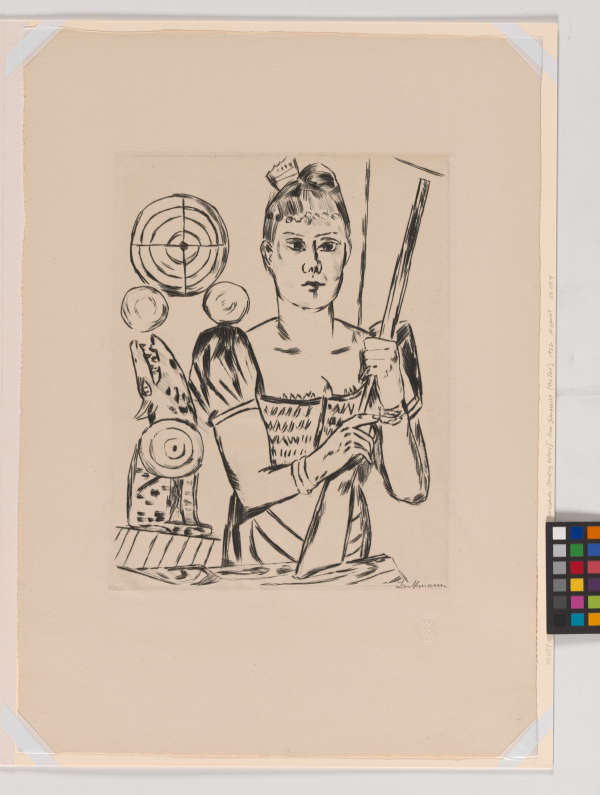

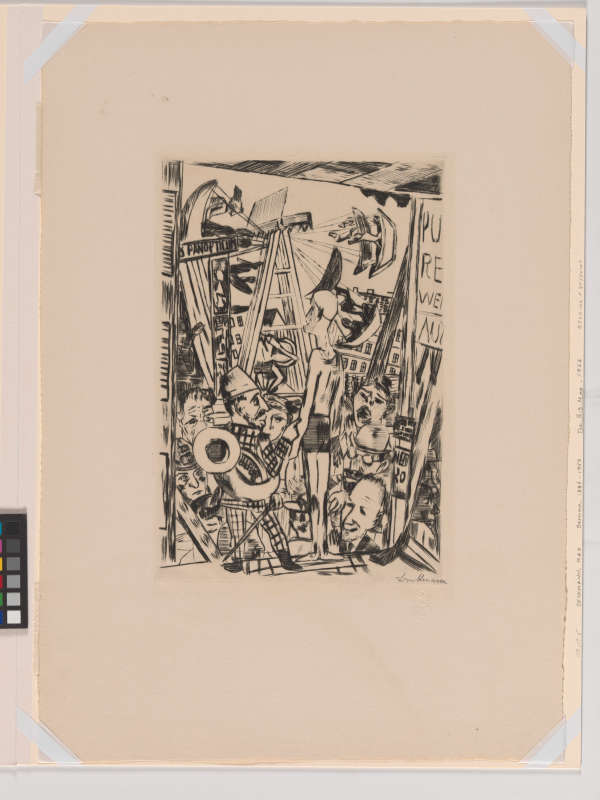

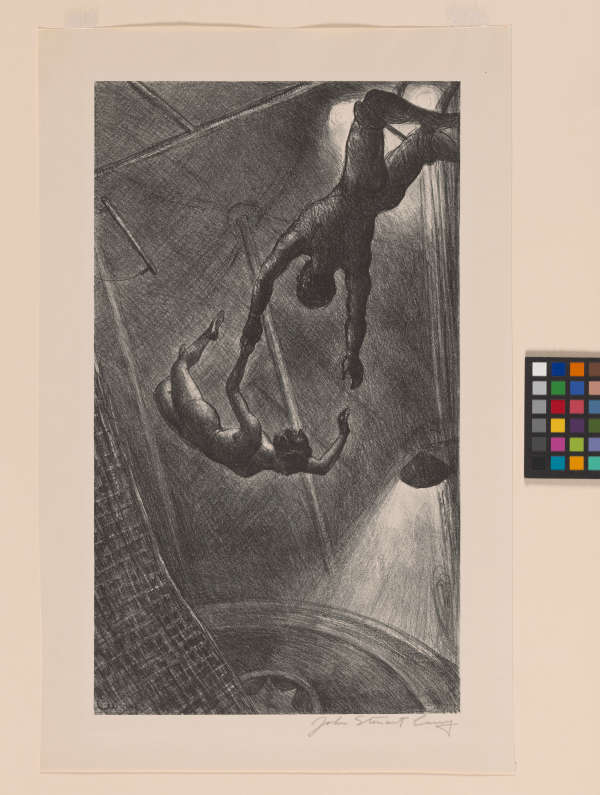

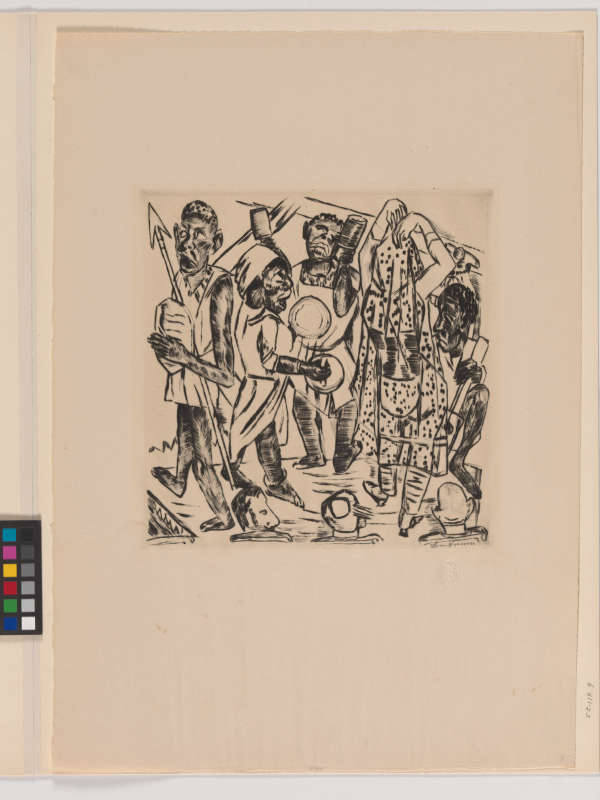

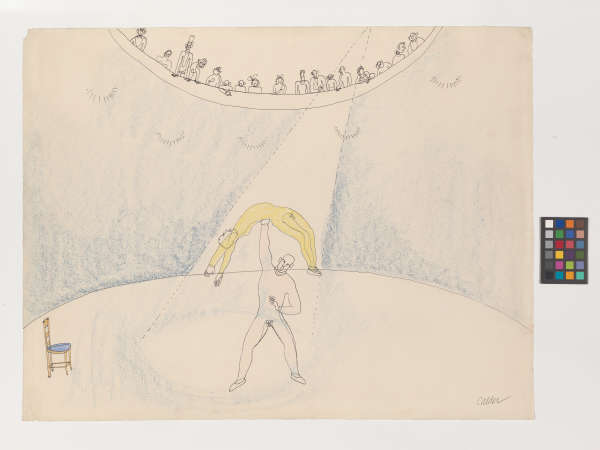

The circus presents human and animal bodies in their extremes, juxtaposing grace, strength, and elegance with the wonderous and grotesque. These characteristics extend to the visual culture of the circus, from ephemeral advertisements designed by now-unknown artists to monumental canvases executed by critically acclaimed painters. The artists whose works are featured in this exhibition delve into both the imagery of the circus and its wider cultural connections, exploring popular entertainment as subject matter and a times using it as a tool for cultural critique.

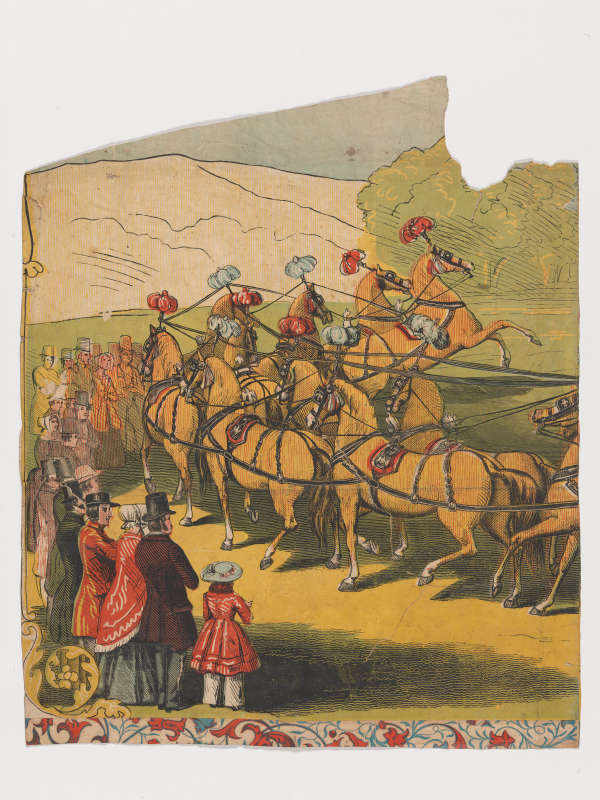

The first modern circus was performed in London in 1768 at Philip Astley’s equestrian school, with the first American incarnation debuting in 1774 in Newport, Rhode Island, with Christopher H. Gardner’s performance of equestrian acts. Between 1850 and 1950, the circus grew to include animal acts, acrobats, and the sideshow, giving rise in the U.S. to Barnum & Bailey’s “Greatest Show on Earth” and the Ringling Brothers Circus, Zirkus Sarrasani and Zirkus Hagenbeck in Germany, the Cirque Fernando (later Medrano) and the Cirque d’Hiver in Paris, and dozens of smaller troupes throughout Europe and the United States.

The rise of the circus was closely tied to the industrialization of the United States and Europe. An increasingly pervasive railroad system enabled touring to small towns as well as large urban centers. The manufacture of circus posters-typically made with woodcut until the 1870s-changed dramatically as widespread use of the technology of lithography enabled poster designers to make more complex and graphically dynamic images in greater quantities. For its audiences, the circus served as both entertainment and education, providing many circus-goers with their first exposure to cultures from around the world, shaping knowledge while simultaneously reinforcing Western rule of, and cultural dominance over, colonized lands.

Alison Chang