Courtesans of the Floating World

Introduction

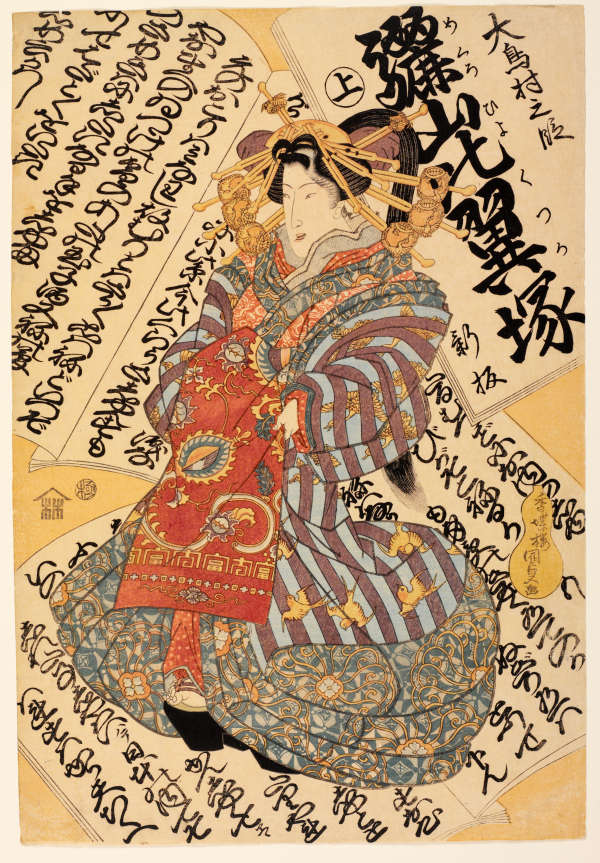

The art of Japan produced during the Edo period (1600-1868) consisted largely of ukiyo-e or "pictures of the fleeting, floating world." These prints, which were intially intended for those too poor to buy paintings, were ultimately admired and collected by people of all classes. Japan's policy of seclusion (sakoku) instituted by the Tokugawa shogunate around 1640 provided the ideal climate for the burgeoning popularity of ukiyo-e. As both war and foreign trade were at once eliminatead, the middle and upper classes susddenly found themselves with both more wealth and more leisure time to dispose of. The populace wanted works of art which celebrated their everyday interests, their heroes and heroines. There were no military escapades and no travel; the males in this society were forced to look to other sources for adventure. The kabuki theatre and the Yoshiwara or Gay Quarters became the predominant amusements. Not surprisingly, nearly two thirds of the prints produced during the 17th and 18th centuries are devoted to these subjects and almsot the whole corpus of portrait pictures depict the famed high class courtesans (oiran) of the pleasure districts.

The pleasure district, which existed in every major city, was an enclosed area with one main thoroughfare and and five or seven intersecting streets. The Yoshiwara was open to all social classes and men wandered the streets socializing with one another or chatting to teh courtesans through the bars of the greenhouses or teahouses. The government licensed Japanese courtesan was a breed apart; condoned utterly by society, she could consider herself "the pride of Edo (Tokyo)." Highly educated, talented, and attractive, she was, in many ways, treated as a princess and thought of as the ideal of Japanese womanhood.

The intellectural equals of the men who visited them, courtesans were expert in a variety of skills including singing and dancing, writing poetry, perfoming the tea ceremony, and flower arrangement. She was a rarefied creature whose opulent coiffure was arranged on a metal frame and held there by long metal or wood pins; her kimonos and obis were made in the latest and most sumptuous silk prints and were far more elaborate than those of other women. SHe spoke in an archaic language and her refinement exceeded that of any other group of women, most of whom were purposely kept uneducated and inactive.

The prints in this exhibition, made by such artists as Utamaro, Harunobu, and Shuncho, depict the gorgeously attired courtesan engaged in some of her numerous daily activities including making up, promenading with her kamuro (attendant), and picnicking beneath the flowering plum trees. Her world seems filled with the most delightful pastimes, completely free from teh worries and restraints whihc plagued the rest of the population. This romantic, carefree image was just the one that the Tokugawa shogunate and the Japanese themselves wished to foster:

...living only for the moment, turning our full attention to the pleasures of the moon, the snow, the cherry blossoms and the maple leaves; singing songs, drinking wine, diverting ourselves in jsut floating, floating; caring not a whit for the pauperism staring us in the face, refusing to be disheartened like a gourd floating along with the river current: this is what we call the floating world... -- Ryoi, Ukiyo monogatari (Tales of the Floating World, ca. 1661).