Design and Description

Introduction

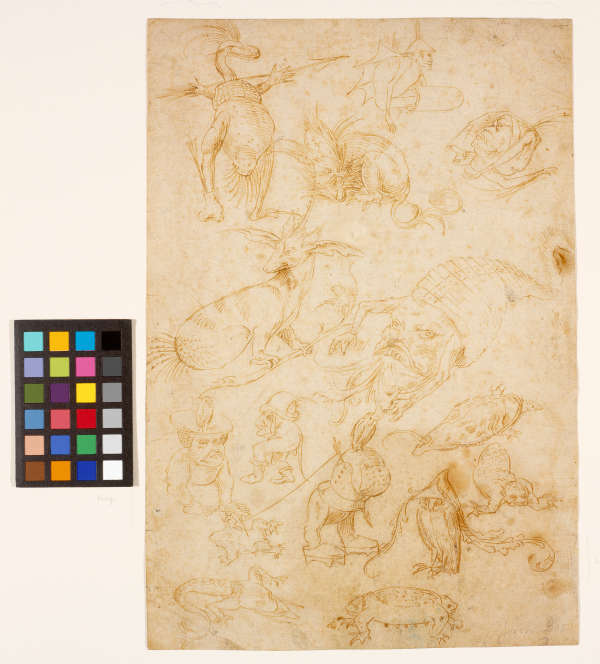

Beginning in the early Renaissance (ca. 1400), artists and their patrons sought new ways to make art and its subject matter correspond more directly to the world of their viewers. In the pursuit of increasingly naturalistic art, drawing became a regular part of artistic practice.

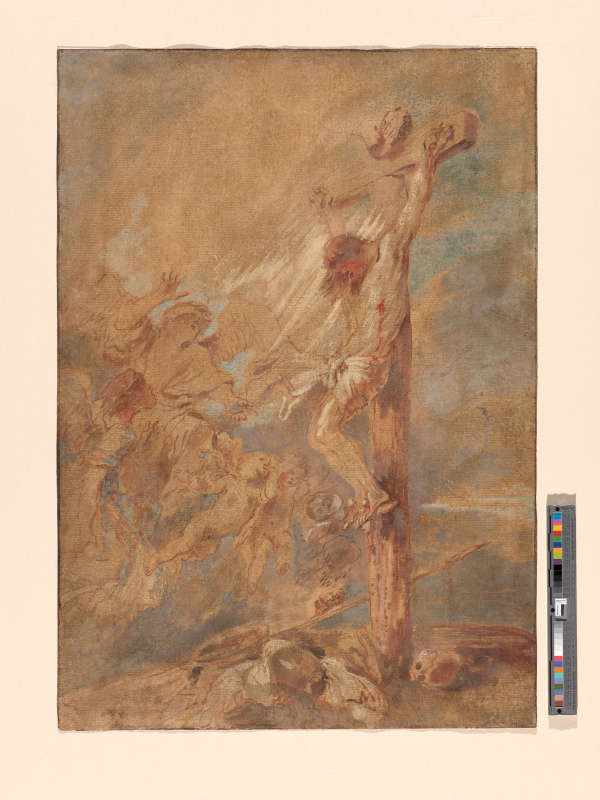

The Italian word for drawing, disegno, also may be translated as “design.” In artists’ workshops and emerging art academies in Renaissance Italy, young apprentices were taught to follow clearly defined steps in the design of frescos, panel paintings, sculpture, and prints. Artists began with free-form sketches that explored compositional ideas and also with studies from life or antique sculpture. These were followed with drawings that explored the effects of light, shadow, and spatial illusion. Lastly, artists created fully realized drawings to integrate all of these design elements into models (called modelli) for the final works.

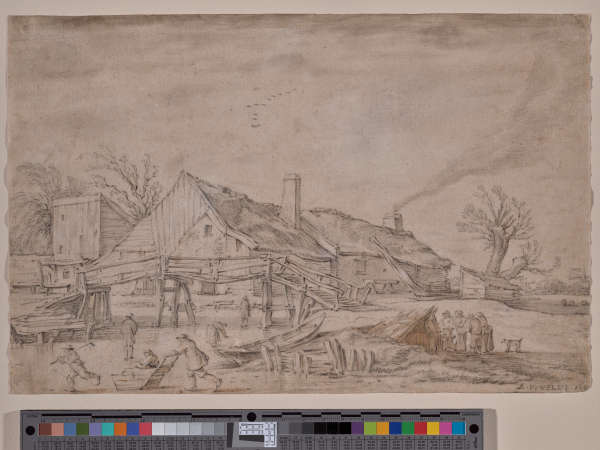

In Germany and the Netherlands, preparatory drawings became common only in the 1550s. Instead, drawings were presented to patrons as finished works or as contractual agreements. They were also used in instruction: artists often made drawings of completed paintings to use as workshop examples. For these reasons, many early Northern drawings are highly finished, emphasizing the descriptive detail, texture, and reflective effects of light for which Northern painters were known.

By the 17th century (Baroque period), artists from all over Europe traveled to Italy for part of their training. As a result, the Italian tradition of systematic design permeated artistic practice throughout the continent. As well, new genres such as landscape emerged with emphasis upon sketching on site.

The Renaissance and Baroque reliance on drawing carried through to the art academies of later centuries, continuing today at RISD as the foundation upon which students base their artistic training.

Emily Peters