Early Exposures

Introduction

Photographic images are ubiquitous in today’s world, but in the 19th century, photography was not only new but awe-inspiring, even magical.

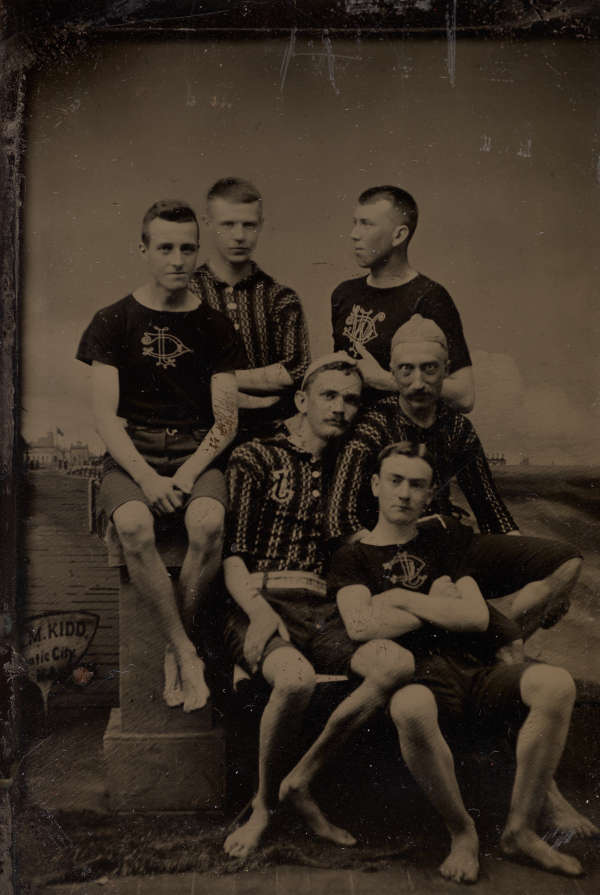

In the early 1800s, several entrepreneurs simultaneously began to test formulas for the best way to create and fix an enduring image on a sensitized surface through the action of light. The daguerreotype, developed by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre in association with Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, was announced to the public in 1839. The daguerreotype process created unique images, capturing human likenesses-its primary use-with astonishing clarity and precision. The calotype followed, introduced to the public in 1841 by its inventor, William Henry Fox Talbot. The calotype process created characteristically soft images with an uneven tonal quality on paper. Talbot discovered he could develop the latent image after exposure, printing it to make a positive. The potential to create multiples generated even more interest around the medium. For the rest of the century, competition-technological, commercial, and artistic-as well as the demands of public taste transformed photography from a costly and cumbersome novelty into a seductive, ubiquitous medium for documentation and artistic expression.

Recalling debates dating to the Renaissance about the purpose of representation, a divide quickly sprang up between those who valued photography for its hard, linear perfection and those who appreciated its possibility for soft-even manipulated-visual effects. For many, photography’s virtue was its faithful witness, recording the faces of loves ones, faraway places, and events as they unfolded. Others valued photography’s potential for investigations that were as poetic and expressive as painting. The highlights of 19th-century photography on view in this gallery represent the broad array of technical processes and approaches to the medium before 1900.

Emily Peters