Glimpses of Grandeur

Introduction

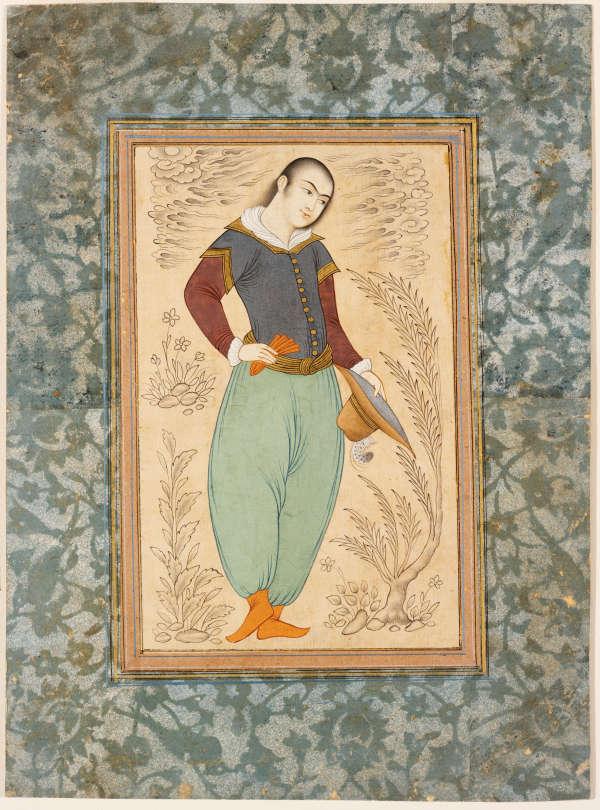

Lavish textiles played an important role in the palace life and the court ceremonies of the Islamic world. Palace interiors were filled with shimmering silks, colorfully embroidered cottons, and intricately patterned weavings. In Mughal India, the most spectacular fabrics were reserved for the emperor's coats (jamas) and sashes (patkas). Mughal emperors took special care to coordinate their ensembles, as is evidenced in miniature paintings that depict the emperor resplendent in his harmoniously colored garments and jewels. This type of arrangement may be appreciated in the Portrait of Emperor Jahangir (acc. no 81.230), an early seventeenth-century representation of the emperor dressed for court, but few actual garments or textiles survive from this time period. The coats and sashes in the Museum's collection give an idea of the opulence that characterized the Mughal courts of India, although they postdate the peak of Mughal political power.

Islamic textiles also played an important role in court disdplay and in royal exchange. Silk was the preeminent luxury fabric, prized for its sheen. Silk costumes, like the Mughal robes displayed in this gallery, announced an individual's identity and social rank. The Safavid helmet and Mughal dagger on display in this gallery served a similar social role in the court context in addition to their practical function in combat.

Commerce in silk was an important component in the long-distance luxury trade of the Islamic world. But silk was not the only item of trade and exchange. Ceramics, rugs, and other objects were also eagerly sought. This gallery features a sampling of these items. The Ottomans and Safavids, in particular, acquired Chinese porcelains (acc. nos. 35.665, 35.666) and emulated the technique in their own vessels. Islamic silks, velvets, and rugs were sought by Westerners, who in turn copied their styles. Some of these derivative textiles, such as Italian velvets made in the Turkish style, become desirable commodities at the Ottoman court and were themselves copied. Jade, a rare and expensive Central Asian commodity, was prized at the early seventeenth-century court of the Mughal emperor Jahangir, who jadelike wine cup is also on display at the center of this gallery. These objects emphasize the lively economic and cultural exchange that occurred between the later Islamic empires and the Far East and Europe beginning in the sixteenth century.