Hokusai's Mount Fuji

Introduction

Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) was seventy years old when he began his quest to depict Mt. Fuji in all its seasons and aspects. In the next five years, he created forty-six designs (ten more than needed) for the print series, Thirty Six Views of Mt. Fuji (pub. ca. l829-1833), and 102 designs for the printed book, One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji (pub. from 1829-ca. 1847). While we have no direct explanation for this sudden infatuation, his choice of subject was no doubt influenced by contemporary religious, literary, and pictorial trends celebrating the famous peak, and more importantly, his own desire for immortality (see Henry D. Smith III, Hokusai: One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji, NY: George Braziller, Inc., 1988).

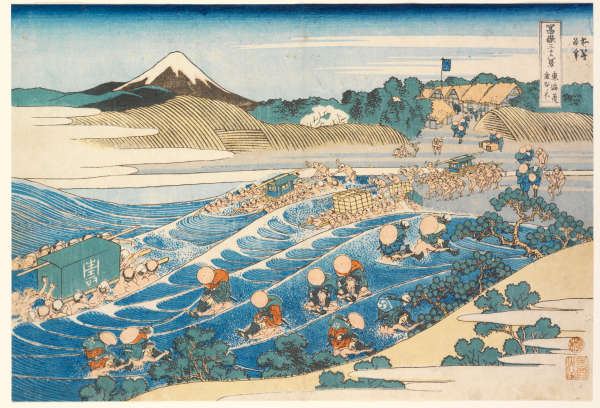

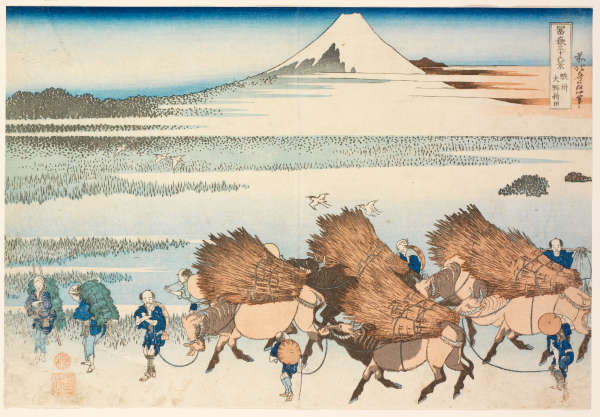

Mt. Fuji has long been cherished in Japanese legends, No drama, and religious worship as the supreme, sacred peak that holds the secret of immortality in its depths. By the nineteenth century, poetic and pictorial genres featuring Mt. Fuji had appeared. New religious worship of Mt. Fuji grew in Edo (Tokyo) that emphasized everyday morality. Miniature Fuji replicas for symbolic pilgrimages dotted the city. Thus, Hokusai's choice to depict Mt. Fuji was not in itself a novel idea. The wonder of this series lies in its innovative compositions, pictorial perspectives, and fresh depiction of working-class commoners, farmers, and rustic life far from the urban world of actors and courtesans.

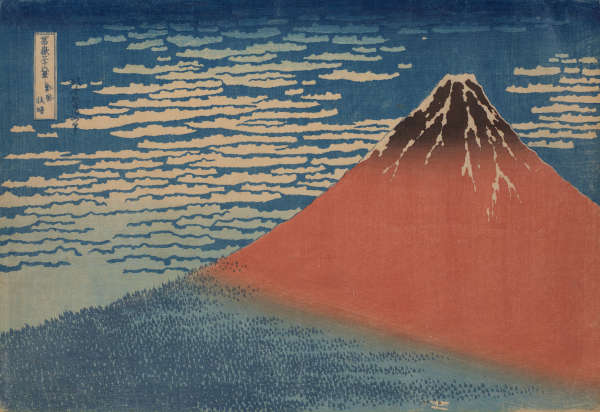

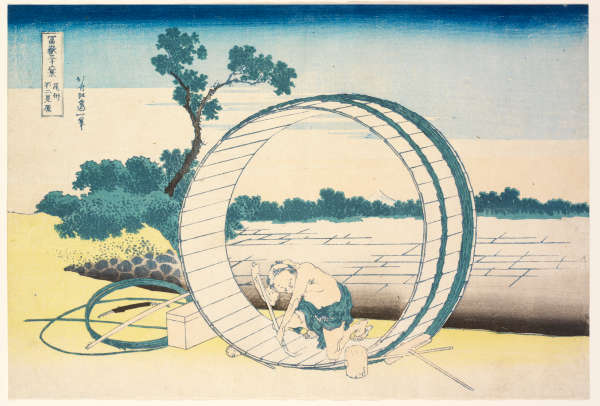

The specific order and dates of these prints are not known, but the geographic or narrative sequence of scenes seems to be of secondary importance compared to the true subject: the constant presence and transcendent nature of the lofty peak in all manner of viewpoints. The prints on display have been grouped into four compositional types: Mt. Fuji framed by the forces of nature, panoramic views of man, Fuji as a background host to travelers moving horizontally across the landscape, and Mt. Fuji as a distant entity peeking behind large foreground images of characters earning a living. At times, the famous peak is hardly recognizable (as in Mt. Fuji Behind Minobu River 18.1184) or not depicted at all (as in Pilgrims at the Summit of Mt. Fuji 20.1187). The peak might be viewed straight on (as in Fine Wind, Clear Evening 20.1185), from high above (as in Mt. Fuji From teh Tea Plantation of Katakura in Suruga Province 20.1181), or from near ground level (and even through a wooden tub, as in Fujimigahara in Owari Province 20.1182). The changes in perspective alter the pitch and volume of the sounds echoing across the landscape. The concern for geometry in compositional design result in subjects depicted with a vivid, fresh clarity. Finally, Hokusai's detailed descriptions of human activity, rarely captured in pictures before, create an impression of a vibrant countryside.

While the scene titles suggest specific locations sketched from direct observation, it is more likely that Hokusai created these images from his pictorial repertoire of human forms and landscape imagery. Also, surviving evidence suggests a correlation between Hokusai's fascination for the unchanging presence of Mt. Fuji and his preoccupation with immortality. In his colophon to Volume One of One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji, Hokusai describes an ambitious dream:

From the age of six I had a penchant for copying the forms of things, and from about fifty, my pictures were frequently published; but until the age of seventy, nothing that I drew was worthy of notice. At seventy-three years, I was somewhat able to fathom the growth of plants and trees, and the structure of birds, animals, insects, and fish. Thus when I reach eighty years, I hope to have made increasing progress, and at ninety to see further into the underlying principles of things, so that at one hundred years I will have achieved a divine state in my art, and at one hundred and ten, every dot and every stroke will be as though alive. Those of you who live long enough, bear witness that these words of mine prove not false. -- Told by Gakyo Rojin Manji (Old Man Mad About Painting)

Although Hokusai was cut short of his hopes at age ninety, it is fitting that after a prolific lifetime of print designing, he should have achieved, with this famous series, his long-sought immortality after all.