Japanese Buddhist Priest Robes

Asian Textiles RA616 (old gallery), Costume and Textiles

Introduction

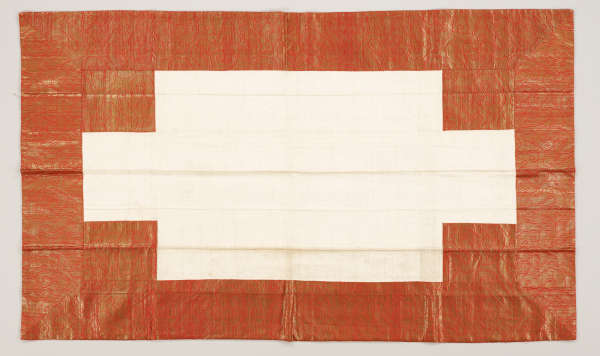

The kesa is a rectangular robe or cape worn draped over the left shoulder by Japanese Buddhist priests and fastened on the right shoulder. A smaller companion piece, known as the ohi, is passed over the free right arm and across the chest under the kesa. Although the form of the kesa is relatively simple, its manner of construction and the symbolism connected with its various parts provide an intriguing insight into the changing philosophical and aesthetic mores of priestly Japanese Buddhist culture. The central field of the kesa is built up from five, seven, or nine vertical strips of frabic in a patchwork construction that ensures subtle gradations of tone, color, and depth that are further enhanced when the robe is in use and subjected to changing patterns of lighting. Small patches of contrasting fabric in each of its corners represent the guardian deities of the four directions (shitenno), while two larger patches near the center of one side represent the two temple guardians or attendants of teh Buddha (nio). In two of the robes on display here, these deities are represented figurally on the relevant contrasting squares (35.283 and 55.410). Frequently holy relics, such as a saint's fingernail or lock of hair, were concealed under these sacred parts of the kesa.

The curious construction of the kesa can be traced back to the original Buddhist vows of poverty; to a time when monks would stitch together their robes from scraps of cast-off material found as they went about their daily rounds. Nine kesa robes from the time of the Emperor Shomu (r. 724 - 756) that have been preserved in the Shoso-in treasury at Horyu-ji temple near Nara, for example, most faithfully imitate this austere prototype. Intended from the start to appear frail and unpretentious, th ey are designed with subtle, cloud-like patterns in mottled shades of gray and brown. The RISD kesas, however, were all made during the Tokugawa or Edo period (1603-1867), by which time the Buddhist priests had developed a less austere aesthetic that contrasts sharply with that of the early Buddhist tradition.

Instead of reusing coarse scraps of cast-off fabric, kesas from this period are frequently made from the sumptuous brocades produced by the silk looms that had been set up in the Nishijin sector of Kyoto by the Shogun Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536-1598). There, many new techniques brought to Japan by weavers fleeing the chaos that surrounded the sinking fortunes of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) in China were incorporated, such as the method of making gold-paper thread. Though these later kesas utilize extremely expensive fabrics, they sitll preserve the original patchwork effect. Morever, they also reflect the persistent belief in the efficacy of adaptive reuse of fabrics in a spiritual context. Sources for this silk brocade included Noh theater costumes, ceremonial court robes, and kimonos donatead or bequeathed to temples by devout women in search of religious merit. Thus beneath the highly luxurious surfaces of these RISD kesas lies a complex layer of symbolism reflecting an attitude towards the pious use of fabric that can ultimately be traced back to the original Buddhist distaste for the trappings of the material world. Here, sumptuous brocade carries a message of poverty with a heavy sense of irony.