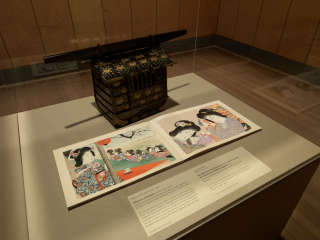

Kunisada's Twelve Month Series

Introduction

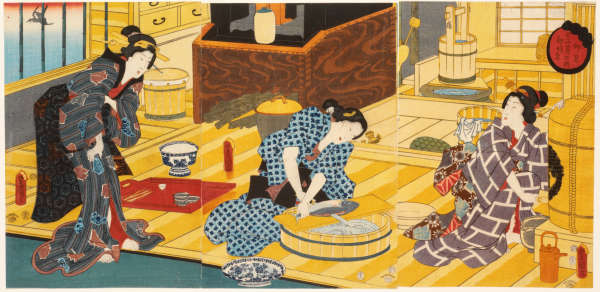

“Twelve Months,” this beautiful set of triptychs by the 19th-century Japanese printmaker Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1865), depicts genre scenes, or scenes of everyday life, in the Edo period (1603-1867). The Edo period (named for the town that is now modern Tokyo) was ushered in by the consolidation of the Tokugawa shogun’s power, which introduced a prolonged period of peace. With the patronage and support of a new class of well-to-do town dwellers (called chonin in Japanese), commerce, the arts, crafts, kabuki theater, and entertainment offered by the teahouses and courtesans of the licensed pleasure quarters flourished, contributing to the development of a distinctive new urban culture.

Japanese prints illustrating genre subjects evolved, at least in part, from an earlier tradition of painting festival and city scenes. Screen paintings of festivals, associated with the seasons, seasonal activities, and specific monthly celebrations, are reminders of time’s passing and of the annual cycle of the calendar. In the 16th century, screen paintings of panoramic city views became popular, their details showing scenes of daily activities. Kunisada’s prints draw their inspiration from these early genre depictions.

Seasonal activities, most performed by women, are Kunisada’s primary subjects. He alternates between mundane pursuits, such as the airing of clothes (The Sixth Month), with the preparation of rice cakes (mochi) for the New Year’s holiday (The Twelfth Month), contrasting the cycle of daily life (ke) with the extraordinary (hare) quality of religious festival days (harebi), and highlighting the passage of time.

The subject of the twelve months was first introduced into the Japanese print repertory in the 18th century by Okumura Masanobu (1686-1764), a highly innovative Japanese printmaker. In contrast to mainstream depictions of kabuki actors and courtesans boldly framed against a simple ground, this new type of work encompassed scenery as well. A century later, Kunisada carried on the seasonal theme, but expanded the traditional triptych format, which featured one figure per panel, by adding additional figures to some panels and by overlapping foreground and background details between panels. Whether set within elaborate domestic interiors or a landscape environment, Kunisada’s monumental compositions are often more unified and dynamic than those of his predecessors.

Note: Until 1873 the Japanese used a lunar calendar, in which the rotation of the seasons began with spring. The New Year, which marked the first day of spring, usually occurred in late January or early to mid-February in our solar Gregorian calendar.

Deborah Del Gais