The Needle's Excellence

Introduction

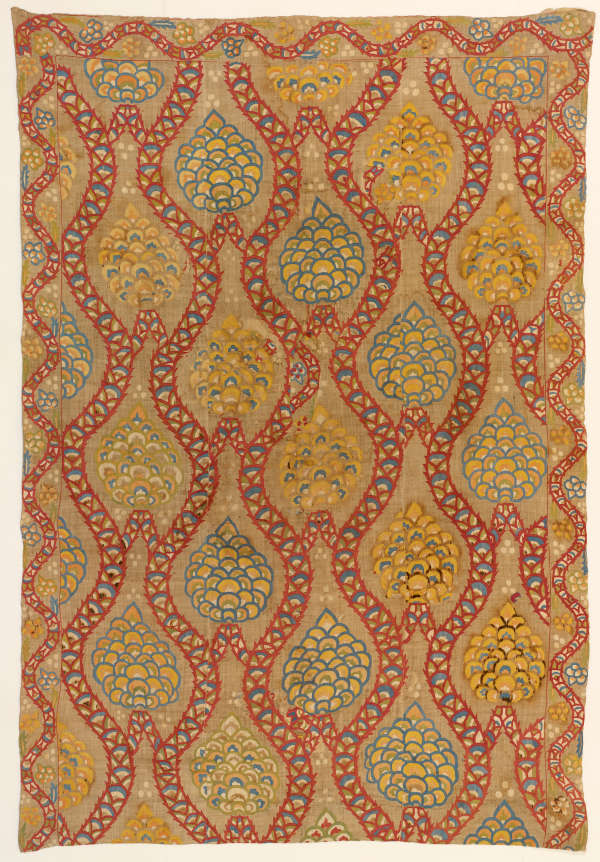

The textile arts in Ottoman Turkey encompassed luxurious woven silks, woolen pile carpets, professional embroideries in silk and metallic yarns on velvets and plain silks, and domestic embroideries in silk and metallic yarns, on linen or cotton grounds. Of these types of textiles, the domestic embroideries have, until recently, been the least studied.

Embroideries in silk yarns on a linen ground tended to be for domestic use: decorative, but retaining a functional element. Textiles large and small, for apparel, utility, or household furnishing, were all decorated with needlework. Design elements were generally disposed to follow the function of the cloth. Long rectangles with plain centers and embroidery confined to the ends were meant to be used as sashes, napkins or towels, depending on the width of the cloth. Large scale floral designs in which all the flowers “grow” in the same direction were probably used as wall hanging or bed covers. Square cloths with centr5al designs and borders oriented toward the corners may have been scarves or wrapping cloths.

Design elements follow those from other textile forms and other Ottoman decorative arts, such as the ceramics displayed in the case in the center of the gallery. From the late 18th century onward, European influence can be seen in the use of architectural elements, shading within motifs, and lighter colors.

The textiles displayed in this gallery were probably all worked by women, but not necessarily for personal use. Skilled needlewomen were often commissioned by others to make special pieces. Most women embroiderers worked in their homes, but around the mid-19th century, women (especially non-Muslims) started working in factory-like workshops. In materials, function, and design, this type of embroidery is urban art.

Madelyn Shaw