Needlework

Introduction

The Deerfield Society of Blue and White Needlework, 1896-1926, was formed in order to revive American colonial crewelwork through organized village industry. The eclectic, and many felt regretful, state of the art of needlework in the late nineteenth century prompted the Society's founders, Margaret Whiting and Ellen Miller, to look for inspiration in the vigor and charm of colonial crewelwork. Sharing the results of their study of early American embroidery with other Deerfield women, Miller and Whiting created a thriving business which achieved national recognition for Blue and White doilies, tablecloths, bedcoverings, etc. The drawings in this exhibit range from sketches of the Society's colonial source material to finished presentation drawings designed to be shown to a client.

The Society prided itself on high standards of craftsmanship and its fidelity to authentic designs and techniques. Their use of the traditional indigo dye depended on by colonial women for its vivid, fast color gave their work its distinctive character and name. The Society's trademark, a D enclosed with a flax wheel, was teh last bit of embroidery to go on a work, insuring that the peice aws up to the Society's perfectionist standards.

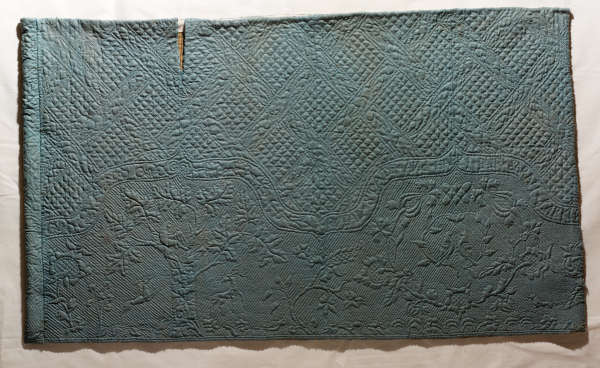

Colonial embroidery is characterized by the use of a minimum of solidly filled forms in order to save the needlewoman precious time and thread. However, what the work loses in detail and intricacy is often gained in strength and inventiveness. Though colonial and European embroidery differ in this respect, both share the eigtheenth century's love of floral and acanthus leaf motifs distributed along meandering, curved lines. The relationship of the embroidered design to the piece itself varied. Some women concentrated on borders which followed and emphasized the perimeters of their work, while others like Elizabeth Reed, used an overall distribution of pattern on a coverlet reminiscent of tapestries or chintz. Because most coverlets were woven in two breadths, then sewn together, and alternative approach which acknowledges the center seam can be found in both Sarah Packard Snell's and Rebekah Dickinson's bisymmetrical designs.

Though the formal artistic training of Margaret Whiting and Emily Miller lent a sophistication to the Society's work not often found in early American pieces, their primary goal was to revive the spirit of colonial needlework. Their attempts to find as much biographical information on thier foremothers as possible demonstrates their concern with the ways in which colonial needlework reflected the quality of its maker's life. Margaret Whiting's belief that needlework "yields to the careful observer many hints of the character of the needlewoman who made them" is as true for us as it was for the members of the Society of Blue and White Needlework.