One Voice, Many Visions

Introduction

The history of American art has been enriched by contributions from African American artists in all mediums. The artists in this exhibition share a cultural identity, but their paintings, sculptures, prints, and photographs also reveal individual artistic visions that are as diverse as their subjects and styles. The exhibition presents a small selection of works produced by African American artists over the past one hundred and twenty-five years. They have been chosen from the Museum's permanent collection and range from late nineteenth-century landscapes by Rhode Island artist Edward Mitchell Bannister and early twentiethcentury sculptures by Nancy Elizabeth Prophet to a 1997 book by Kara Walker. In One Voice, Many Visions, individual interests and personal histories emerge, connect, and contrast in works that enhance the range and perspective of American art.

In 1913, through a major bequest from Providence collector Isaac C. Bates, RISD became one of the first museums to acquire the work of Edward Mitchell Bannister, an African American artist whose landscapes reflect the scale, technique, and subject matter of the French painters of the Barbizon School.

Bannister's painterly New England views represent the enduring appeal of intimate local landscapes to American artists and collectors. In contrast to Bannister's secular spirituality, religious sentiment is more overt in the art of Henry Ossawa Tanner, a successful academic painter who studied with Thomas Eakins and settled in Paris in the late nineteenth century.

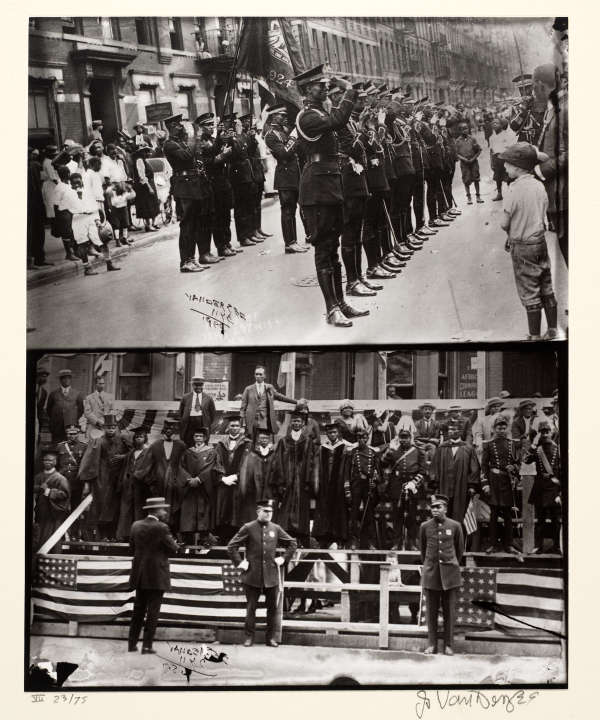

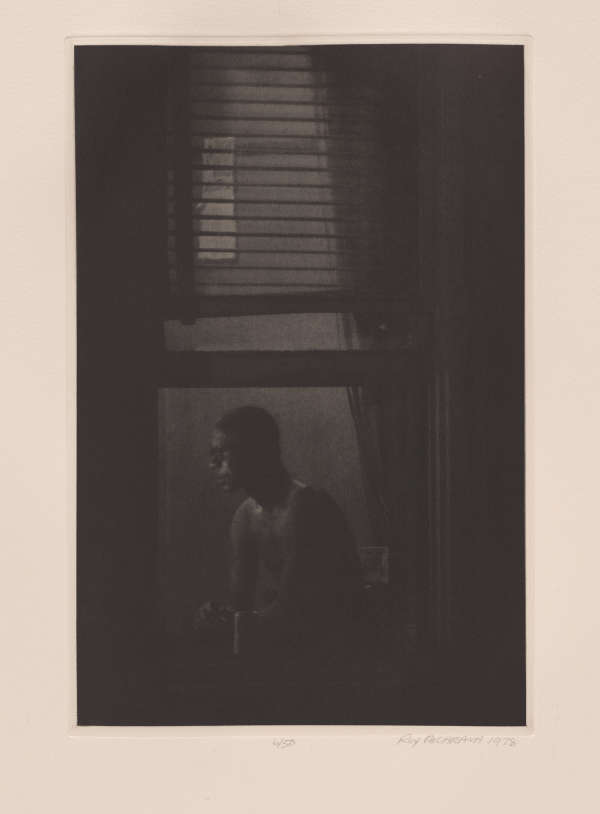

Around the tum of the century, American artists began to explore a strong realist aesthetic that supplanted both landscape and academic figural imagery with scenes of urban work and culture. In the 1920s, James VanDerZee photographed bourgeois interiors and African American families in fine attire during Harlem's renaissance of culture and prosperity. Jacob Lawrence's brilliantly colored gouaches explore social problems and opportunities after the Second World War, while Roy DeCarava 's black-and-white images and Vincent Smith's etchings reveal both the vitality and social challenges of the 1950s and 1960s.

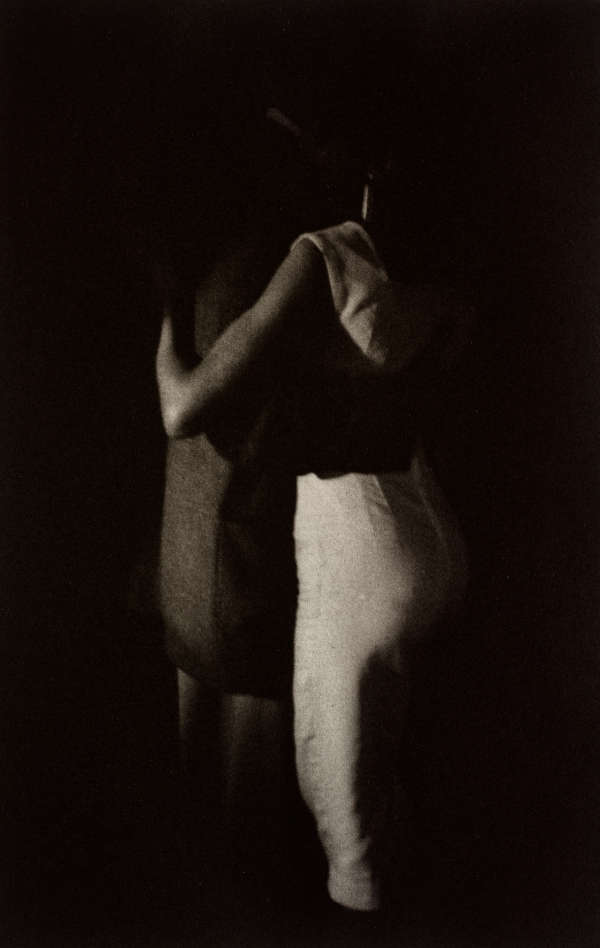

The narrative tradition of the first half of the twentieth century became a touchstone for many of the artists who followed. One Voice, Many Visions indicates the strong figural direction that emerges in the work of younger artists such as Joseph Norman and Alison Saar, whose prints interweave social and mythological themes. In the photographic images of Loma Simpson and Carrie Mae Weems, poetry is partnered with images that reflect deep connections with African and African American culture and invite private contemplation. In contrast, Kara Walker's compelling silhouettes are both delicate and unflinching, rich in movement and detail and provocative in meaning.

One Voice, Many Visions also includes the work of artists whose interests lie in painterly surfaces and personal marks. Donnamaria Bruton's painting Me and My Dad presents biography through metaphors defined by drawing and collage of interior spaces and features. Nanette Carter's sweeping gestures and Mahler Ryder's complex constructions suggest movement and music in visions that reject both words and images. This intimate cross-section of work by African American artists resonates with individual styles that have flowed with and influenced the direction of American art for more than a century.