Of Peonies and Dragon's Toes

Introduction

When Manchu armies from the north swept across the Great Wall of China in 1644, they found the native Han society used to strong tradition and clans organized in postions of importance from top to bottom. To the Chinese, a man's place in his family was, and still is, of great importance, and everything he did was designed to bring honor and sucess to his family, to future generations through the male heirs he would provide, and to his ancestors. According to law, his clothing and that of his family had to reflect his position in his clan.

Taking advantage of this, the conquerors set up a Chinese-style bureaucracy that descended from the Manchu emperor in strict hierachical order. The Manchu also insisted on imposing their own style of dress on everyone in government service. At one stroke, this established both a means of control and a way of distinguishing the Manchu from the Han, since the Manchu held all the high-ranking postions in the government.

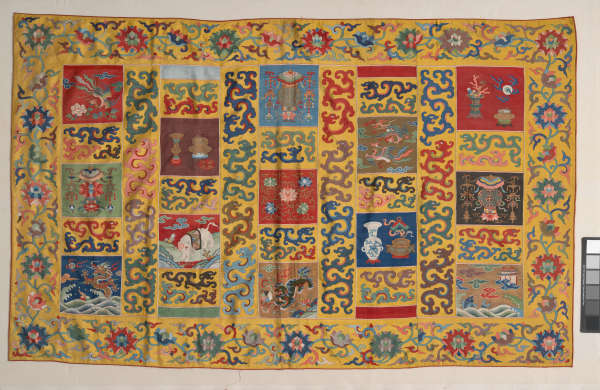

Between 1644 and 1911, when the Manchu Empire fell, strict laws prescribed that Chinese officials wear a single braid of hair down the back of the head (the queue) and long robes decorated with the dragons that stood for the power of the emperor. High officials were distinguished from lower officials by the colors and other symbols on their robes and by badges of rank. The emperor wore yellow or blue robes with five-clawed dragons as his rank badge, while lesser officials wore blue, brown, or beige robes with either five or four-clawed dragons, depending on their rank. In addition they wore rank badges ranging from the crane of a first rank official to the ninth-rank paradise flycatcher. Scattered throughout the decoration of the robes were symbols for Chinese values: peonies for riches, cranes for long life, the pomegranate of fertility, bats for happiness. The wives of these officials wore similar clothing, complete with rank badges, on formal occasions.

By the 19th century, when most of these robes were made, strict tradition had softened somewhat. Most officials now wore fiveclawed dragons, and many symbols had become merely decorative elements, but official robes still reflected the Confucian world with waves at bottom, the land mountain protruding from the waves, a cloudy sky, and dragons to represent the Emperor, the center of the universe.