Samurai, Soldiers, and Idealized Militarism in Japanese Prints

Introduction

Woodblock prints produced during the Edo Period (1603-1867) portray the samurai in idealized designs of battle and travail. Images made in the subsequent Meiji period (1868-1912) depict moments during Japan's wars with China (1894-95) and Russia (1904-5). The samurai code of military and personal ethics was transformed into a modernized military culture with the rise of nationalism in the late 19th century.

The Edo Period witnessed efforts to formalize the distinctions between different social classes and to codify their ideal "way" or "path" (do). Edo legislation was based on a four-tier system with the samurai warrior at the top followed by peasant, farmer, artisan and merchant. The bushido or warrior's way was the code of the samurai class at a time when, in reality, they were more active in peacetime administration than active military duty. This situation engendered idealized and fantastic woodblock prints of historical moments and figures in samurai history for popular consumption.

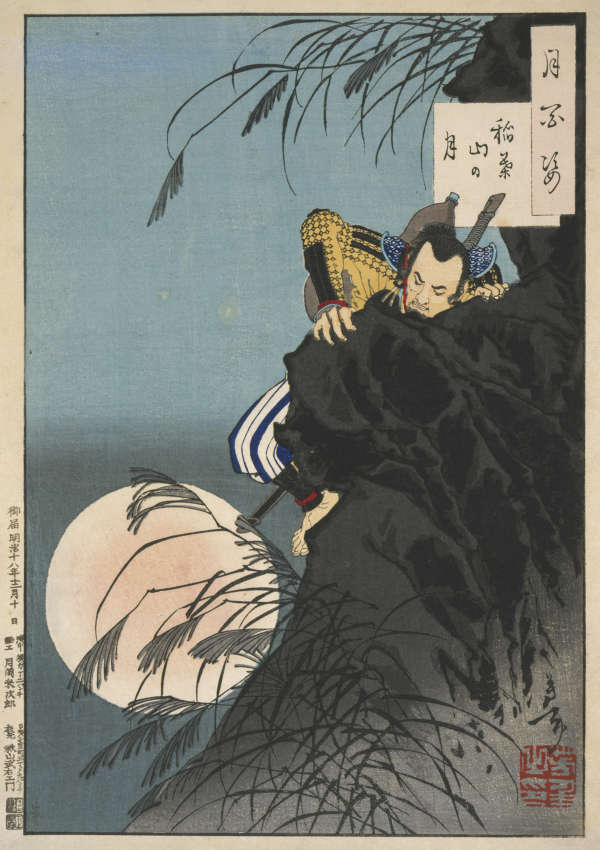

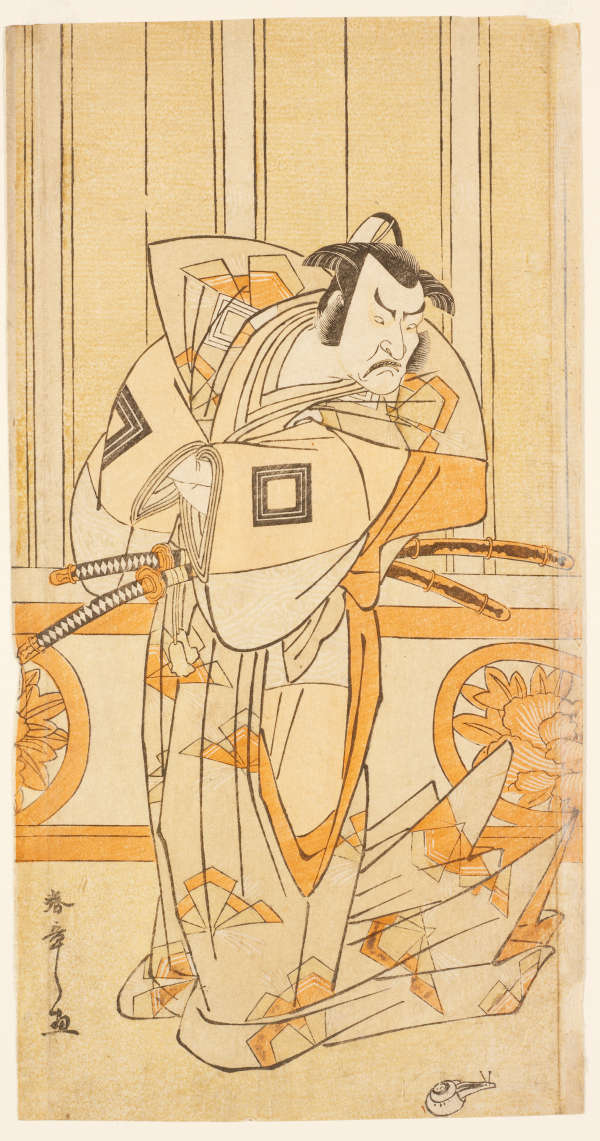

Samurai and battles were a favorite theme in the Kabuki plays of the Edo period. Shown immediately to the left are several images of warriors, including one in the elegant long pantaloons for those of courtier rank. As upholders of bushido, with its aim of displaying the highest possible ethical standards in both victory and defeat, samurai were a favorite subject in Japanese literature, drama, and oral tradition as well as in prints. Kuniyoshi, always a dramatic designer of prints, shows his skill in several elaborate triptychs of samurai in battle. In The Brave Death of the Kusonoki Clan in Their Fight at Shijonowate Against the Ashikaga Shogunate, the artist focuses on the heightened terror and bloody violence of men that participated in a famous historical battle. In other Kuniyoshi images, such as A Japanese Daimyo Vessel Off the Coast of Kyushu During a Storm at Sea, the warrior theme seems subservient to the intense drama of the stormy ocean. Two prints by an artist active into the rapidly westernizing Meiji period, Utagawa Yoshitoshi, show a more atmospheric and romantic approach to the warrior theme. An Armored Samurai Climbing the Cliff in the Moonlight is a memorable example of this style, one which emphasizes the individual spiritual and physical fortitude of the samurai more than earlier images.

The legacy of the samurai, particularly high-ranking warriors, is not only one of militarism. Upper-class warriors had close connections with the Zen Buddhist establishment. For example, some high-ranking warrior families patronized Zen temples in their home provinces or financed the founding of sub-temples. Warrior families would also send their sons to Zen monasteries for an education. Their patronage of Zen naturally led some cultured men to become accomplished poets and authors. Throughout Japan, the second half of the sixteenth century was marked by a great surge of construction, as warriors built fortified castles. Although few survive today, we know from records that these castles were elaborately decorated inside. Paintings were commissioned to decorate the doors and walls, both austere sumi ink paintings and bold polychrome landscapes and animals befitting the most ostentatious of patrons.

In the seventeenth century, when the relatively peaceful Tokugawa shogunate was established, the warrior class continued to serve as custodians, practitioners, and patrons of the arts and Buddhism. The triptych print by Hiroshige and Kuniyoshi of Warriors by the Temple of Daibutsu at Kamakura shows a battle, but undoubtedly these men worshipped here, too. The tea ceremony, the ceramic bowls and other utensils for which are shown in the adjacent gallery, was perhaps the most refined of the later arts the warriors patronized.