One of the extraordinary virtues of exhibiting contemporary art in the context of a comprehensive museum collection is the opportunity it inherently presents for one to see how the art of the present extends styles, sensibilities, and concerns of works from throughout art history. Martin Boyce’s mid-career survey exhibition, When Now is Night, allows us to see how the artist’s own work has evolved over the course of 20 years, while also shining an intriguing new light on works in the RISD Museum’s collection by artists and designers of the past.

Perhaps the most direct relationship between Boyce’s work and objects in the RISD Museum collection (aside from three works owned by the museum: Ventilation Grills (Punching Through the Clouds) [2004], We Are Still Here (Think About Why We Are Still Here) [2005], and the wall painting House Blessing (from the White Album by Joan Didion 1979)[1999]) is found in several sculptures in the exhibition which feature variously altered leg splints created in 1942 by famed designers Charles and Ray Eames for the United States Navy. An original Eames splint is currently on view (alongside another iconic Eames production, the 1948 DCW chair) in the Granoff Modern and Contemporary Galleries. Though fundamentally designed to provide functional support for the legs of American servicemen injured in World War II, the splint’s elegantly sculptural form encourages a more purely aesthetic appreciation, a condition reinforced by Ray Eames’s own transformation of the mass-produced molded plywood object into a discrete work that she considered a sculpture in 1943.

Boyce has incorporated Eames splints in sculptures throughout his career, and a number of the works presented in his exhibition feature the object portioned into abstract or mask-like forms. Discussing his incorporation of design objects by Eames and other midcentury modernist designers, Boyce has stated that they “definitely engaged … a particular dialogue, not a critique of the objects as such but a critique of their accumulated ethos which … had changed under the cultural and economic pressures applied upon them.”1 This initial exploration of how Eames-designed splints and storage units started as more universally accessible mass-produced objects only to become hyper-fetishized luxury design items (due equally to the quality of their design and their relative scarcity in the marketplace, a status confirmed by their presence here and in other museums around the world) has expanded into a less specific and more expansive use and interpretation of these materials. As Boyce’s practice has developed, the leg splint has continued to appear in various sculptures. It is painted black and refashioned to mimic Ray Eames’s sculptural transformation in the mobile Fear Meets the Soul [2008], and fragmented into a smaller portion and painted black to suggest a non-Western ritual mask form in Night Tulip [2009].

In both instances, the splint forms prompt an interrogation of their relatively recent role as precious “art” objects, but also begin to transcend that intentionality and speak to other considerations—most significantly, their evocation of the body and other organic phenomena. While the allusion to the body is maintained in Fear Meets the Soul, with the splint becoming an unsettling and almost macabre representation of a severed human leg, its evocation of an object meant both to cover, if not necessarily represent, a person’s face is somewhat more oblique in Night Tulip. In the latter instance, one might consider how masks, while directly connected to the human body, often take on non-human characteristics or, indeed, make the wearer more inhuman—a quality shared by every masked horror-film antagonist.

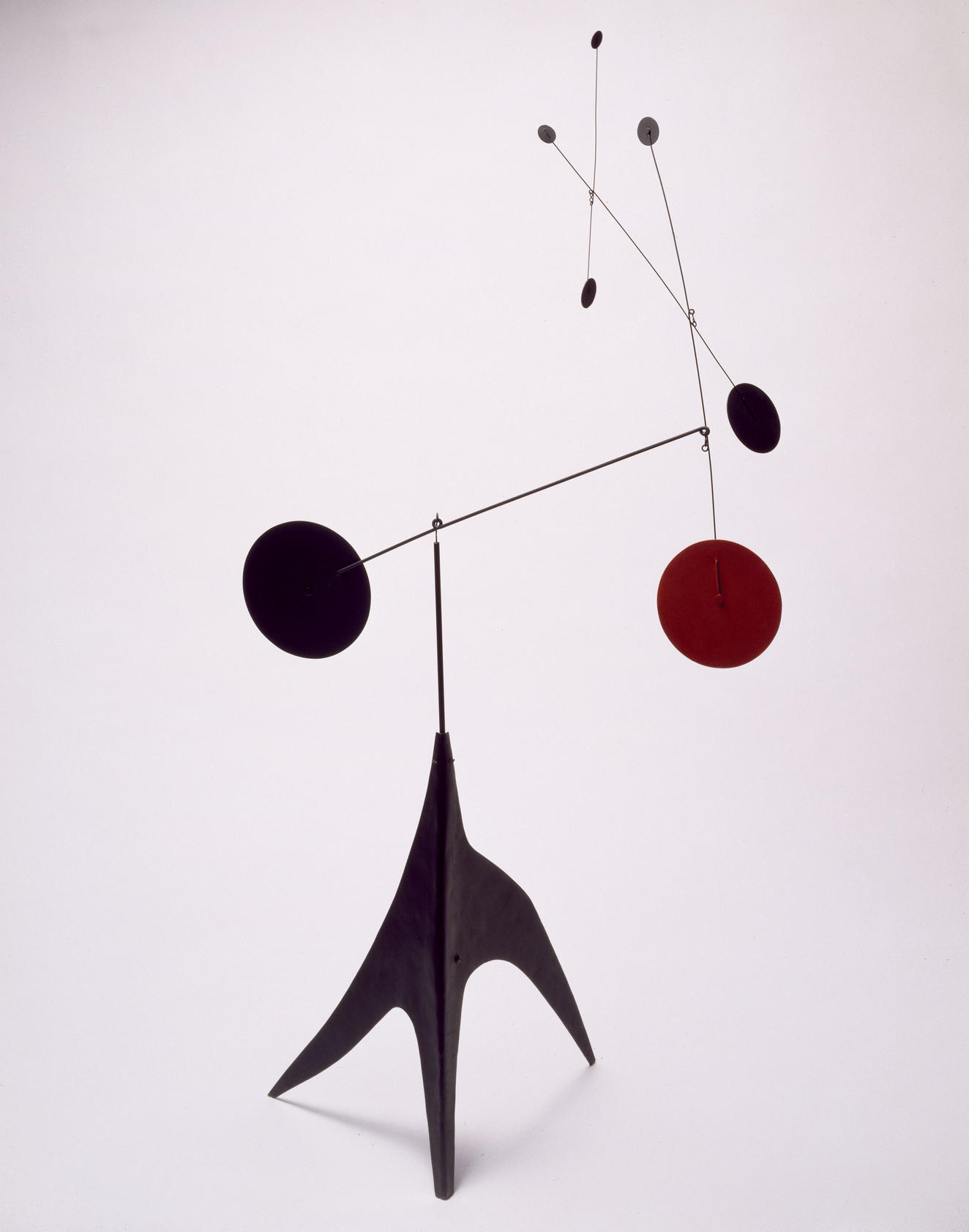

The Eames splint in the RISD Museum is currently placed in front of a 1957 work by another artist of critical importance to Boyce’s practice—Alexander Calder. While the “stabile” format represented in Calder’s Untitled is featured in some of Boyce’s works, it is Calder’s “mobile” sculptures that inform numerous works in Boyce’s show. The RISD collection also boasts the mobile-stabile synthesis A Mobile With a Stabile Tail [1947], in which the usually suspended mobile structure is “grounded” by a stabile base. Calder’s mobile forms combine a sense of structure and order in the armature supporting abstract forms at their ends, with a “liberated” aspect of motion with the various parts able to assemble themselves into multiple configurations based on the ambient conditions of the space in which they are presented, from a breeze passing through, for example, or from the movement of people in the room. Boyce’s works such as Anatomy (for Saul Bass) and We Pass But We Never Touch [both 2003] (and the aforementioned Fear Meets the Soul) tap into Calder’s dialectic of freedom and constraint while replacing the geometric forms at the ends of a typical mobile’s framework with portions of Arne Jacobsen Series 7 chairs. This gesture “corrupts” the otherwise elegant and graceful nature of Calder’s original concept by incorporating objects that are not only the opposite of aerodynamic but also introduce a macabre corporeality in their either direct or implied relationship to the human body.

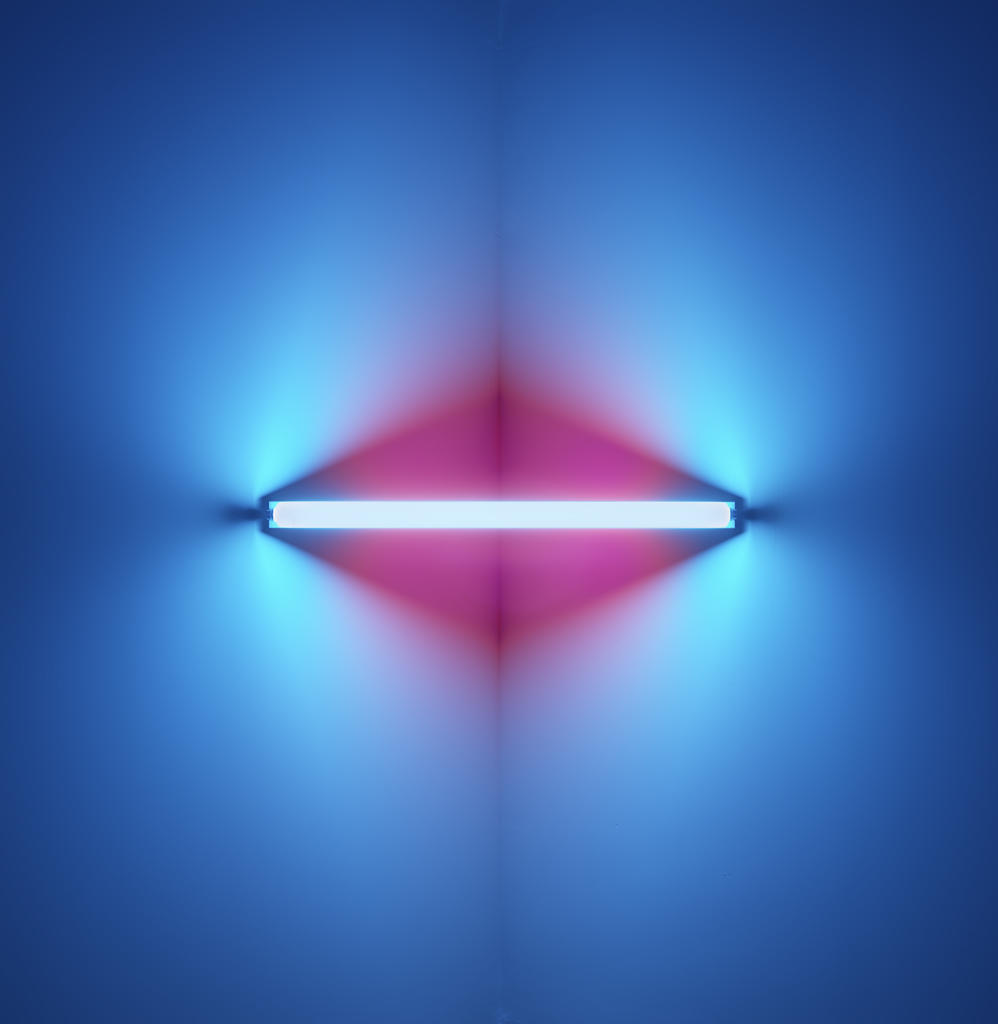

One of the two parts of Boyce’s major installation When Now is Night[2002] is a network of fluorescent lights that forms a giant spiderweb that is suspended above the viewer. One cannot contemplate the use of the fluorescent light fixture in contemporary art without considering the precedent set by the iconic American minimalist sculptor Dan Flavin. The RISD Museum's *Untitled* work from 1970 by Flavin provides a compelling comparison with Boyce’s more recent installation. While Flavin’s engagement of the fluorescent light often involved a more extensive use of multiple bulbs that occupied a broader amount of space, this particular work is remarkable for its simplicity in occupying the corner of a room and the surrounding space with a haunting bluish-purple light—the result of the placement of a red bulb and a blue bulb back to back. Flavin’s use of the fluorescent light suggests how it might transcend its mundane institutional functionality through the basic addition of color and strategic placement in a space. Boyce’s presentation takes the same object to a different degree of sublimity while maintaining its association with quotidian functionality. The lights in When Now is Night are suspended from the ceiling in a manner befitting their installation in office and institutional spaces, yet their assembly in the form of a spiderweb draws on this associations with human experiences of fear and entrapment. Where Flavin’s simple use of this ordinary material prompts an appreciation of the otherworldly beyond, Boyce’s spectacularly complex arrangement conversely grounds us in the very real and unsettling concerns of everyday life.

Martin Boyce: When Now is Night is on view from October 2, 2015 until January 31, 2016.

Dominic Molon

Richard Brown Baker Curator of Contemporary Art

- 1Martin Boyce, “A Conversation Between Martin Boyce and Christian Ganzenberg,” in Martin Boyce, Renate Wiehager and Christian Ganzenberg, eds. (Cologne: Snoeck Verlagsgesellschaft and Daimler Art Collection, Berlin, 2012), 51.