Dubbed a travel coat by artist and designer Christina Kim, this is a garment made for journeys long and far, both real and imagined, for traversing territories in the mind as much as in the physical world. Writer Elizabeth Spelman has provocatively and insightfully described repair as “the creative destruction of brokenness.”1 Here design itself is an act of repair. Kim’s Los Angeles–based label dosa and this coat in particular offer a flexible, empowering space for recognizing and appreciating ruptures and chasms in the fast-fashion system. Here a garment and the global narrative of its making act as a binding unit, connecting its wearer with the labor of distant artisans and suturing the link between consumers and makers. It also turns consumers into makers as they inhabit and care for a garment that morphs and develops with them over time.

This coat is brand new. It is crisp and unworn, yet creased and cracked and somehow visibly evincing many layers of lived histories in its making, so much so that it has the aura of an old soul despite the fact that it arrived at the museum in mint condition. Handling the coat’s waferthin body effects a multisensory experience. The rustle and crackle of the lightweight, papery cotton give rise to the disarming sensation that it might blow away, while the lustrous glazed surface contains color so rich and blue—so dense and fathomless and emitting scents of earth and animal—that one is tempted to think of it more as carapace than coat, climbing into its warm and protective body.

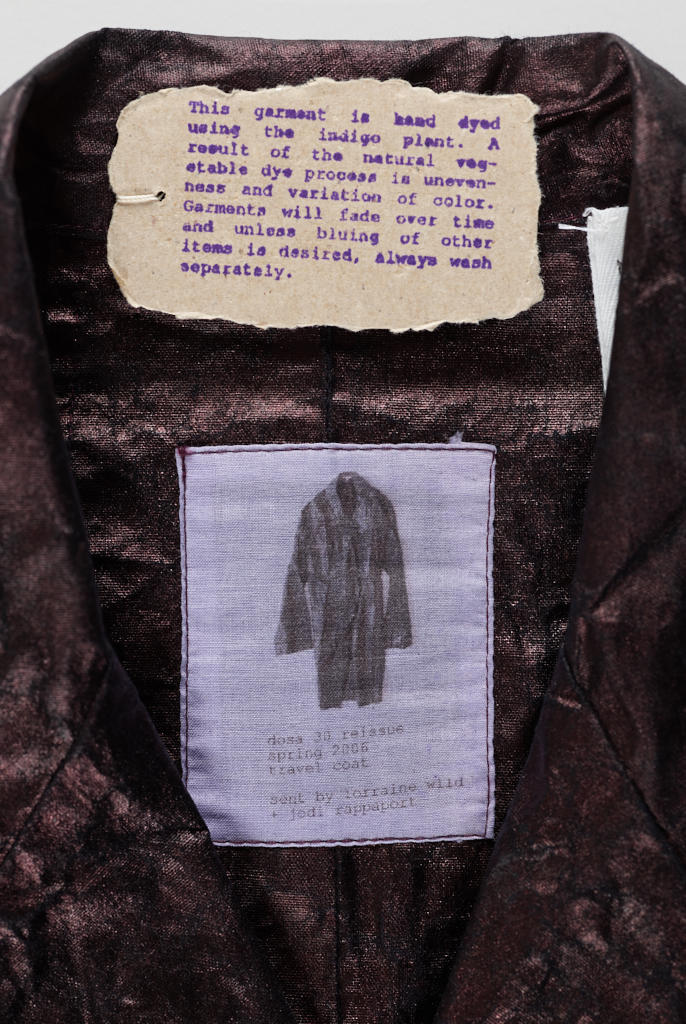

Such is a firsthand impression of the coat’s exterior. Unbuttoning the envelope of the fabric and moving to the interior reveals a cloth label printed with the ghost image of a strikingly similar garment that appears aged and tantalizingly softened with years of wear and subsequent care (Fig. 2). Typed text below the hazy illustration presents some of the coat’s secrets: “dosa 30 reissue / spring 2006 / travel coat / sent by Lorraine Wild / + Jodi Rappaport.” Another label, this one of raw-edged handmade paper, tells us that the garment was “hand dyed using the indigo plant” and alerts us to a probable future of color shifts and variations, of eventual fading with use and potential “blueing” of adjacent items as the hue travels with the coat, rubbing off, reflecting habitual movements, and thus recording the wearer’s journeys.

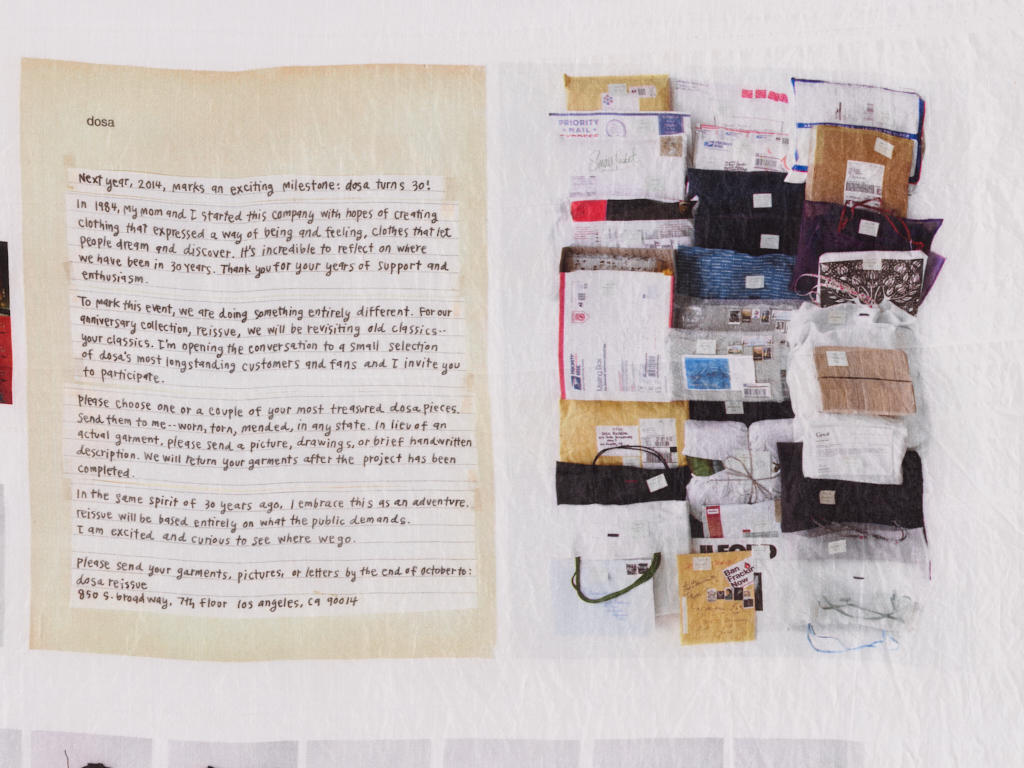

The recognition of a garment’s power to serve as a talisman as its wearer navigates life’s vicissitudes lies at the core of dosa’s 2014 Traveler “reissue” collection. To mark the milestone of dosa’s thirtieth anniversary, Christina Kim sent a personal letter to 150 customers and friends who have supported the label’s ethos over the course of its own threedecade-long journey. She wrote: “In 1984, my mom and I started this company with hopes of creating clothing that expressed a way of being and feeling, clothes that let people dream and discover.” She went on to explain that the anniversary collection will revisit “old classics—your classics” and, for inspiration, asked for a favor: “Please choose one or a couple of your most treasured dosa pieces. Send them to me—worn, torn, mended, in any state.” A scarf issued as part of the collection illustrates the letter, as well as the responses it elicited (Fig.3). Beloved dosa garments folded into mailing boxes and hand-delivered tucked into the company's signature scrap-fabric bags arrived by the dozens, including two well-worn versions of the indigo-dyed-travel coat from dosa’s Traveler 2006 collection, individually sent by creative producer Jodi Rappaport and graphic designer Lorraine Wild (Fig. 4).

After the 2014 collection was produced, Kim described her design intention as wanting to “capture a sense of returning home. For weeks, I reviewed and studied thirty years of archives—mesmerizing color palettes and textiles chronicling all the places I traveled and artisans I met. With every piece of dosa clothing, there is an imprint of me that is passed along, becoming a part of someone else’s story.”2 Over the decades, Kim has collaborated with and worked alongside highly skilled practitioners of traditional crafts from around the world, including artisans connected with sewa (Self-Employed Women’s Association), the largest single union in India; paper makers in a cooperative in Oaxaca, Mexico; knitters in a Bolivian fair-trade studio; a saddlery business in west Texas; and indigo cultivators and dyers in southwestern China. Kim’s express purpose in engaging with makers employing time-honored skills and traditions is lodged in the fact that the materials they produce will last long, transforming and, as such, melding with the wearer to add many more layers to an already rich history of making and creativity. According to Lorraine Wild, whose timeworn coat was one of the inspirations for the version in the RISD Museum collection, “Christina always had that line she called ‘Traveler,’ and I think that this coat exemplifies all that is implied in that word: the invention of something coming out of the astute observation and curation of things encountered by a (particularly talented) global design-citizen.”3

To enrich the experience of handling and wearing the otherworldly deep-blue textiles used in select garments from the Traveler 2006 Mood Indigo and 2014 Reissue collections, new owners of these garments received as a gift from Kim a richly illustrated book, Imprints on Cloth: 18 Years of Field Research among the Miao People of Guizhou, China by Sadae Torimaru and Tomoko Torimaru.4 In the early 2000s Kim traveled to remote villages in China’s Guizhou province with scholar Sadae Torimaru and textile artist, researcher, and curator Yoshiko Wada to observe firsthand the complex process of indigo production and dyeing practiced by people of the Miao ethnic group. The textiles used in her ensuing collections— of a color palette described by Lorraine Wild as “that undefinable or mutable maroon/blue-black/rusty/metallic color that seems ‘alive’”5 —were produced by makers with whom Kim fostered close relationships during her travels.

In the Miao households observed by Sadae Torimaru and her daughter Tomoko, who is also an independent textile scholar, the preparation of the indigo vat is a complex routine carefully orchestrated around the belief that the dye is indeed alive and the color awakened through constant attention and ceremonial offerings. The multistage, time-intensive process starts with cultivating indigo plants and ends with their metamorphosis into a paste yielding a deep dark-blue tint: indigo leaves are soaked and soaked again with lime for days and stirred, left to rest, and stirred again until a blue foam develops at the top of the vat and then disappears, leaving at the bottom a rich and muddy blue paste. The indigo pigment then undergoes yet another odyssey lasting at least two weeks, which instigates its transformation into a fully active indigo dye that transforms textiles into a marvel of azure color that deepens with each dip into the vat.6

The cotton plain-woven textile of RISD’s dosa travel coat was dyed in this way, and then further subjected to several more steps that transformed it into the lacquered, crackled indigo sheath of its present state: it was first beaten with a wooden mallet; immersed again and again in plant extracts to add the subtle reddish tint; soaked in an extract made from water-buffalo skin; and then beaten once more to give it its distinctive glossy finish.7

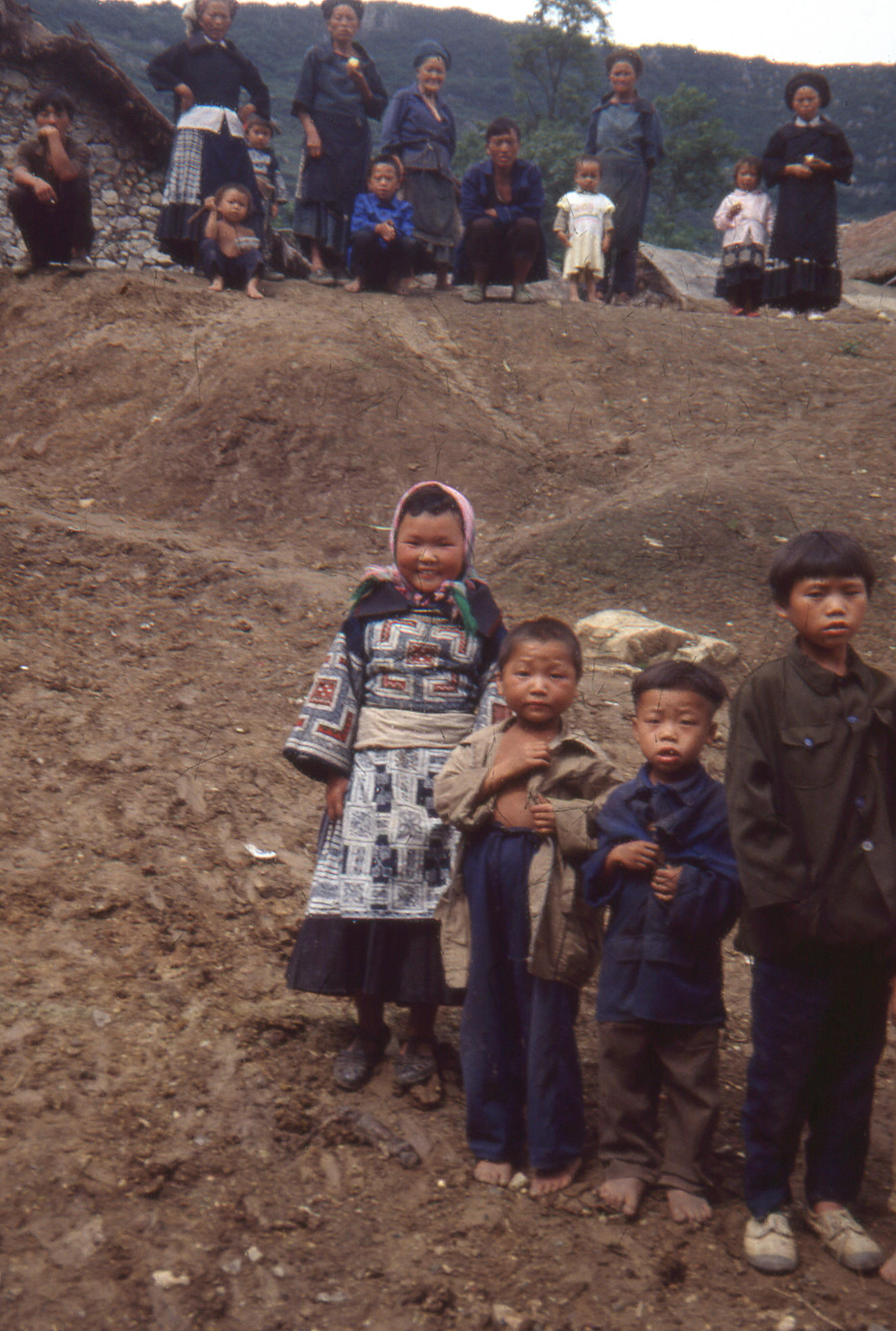

The finished textile’s journey from the skilled hands of the Miao artisans in China to those of the sewers in dosa’s Los Angeles studio contributes to the wrinkles in its surface. These cracks are exacerbated by the push and pull of the sewing machine as the sewer reckons with the textile’s narrow width and unyielding lustrous surface to shape the pieces into a silhouette that, according to Kim, was both inspired by the Western-style Communist-issued jackets worn by Miao boys (Fig. 5) and a German military coat in her personal collection.

Lorraine Wild notes that she bought her travel coat because it felt “tough”: “The coat, with its safari-style pockets and straight cut seems unisex . . . and very ‘urban’—a piece of streetwear, a bit of armor.”8 There began Wild’s coat’s next phase of transformation, shaped by her own contexts and perspective. Without a wearer like Wild, the RISD Museum’s coat will become a piece apart while also remaining open to multiple interpretations and narratives in the minds of the museum audience—a challenge to singular notions of authorship and ownership. Like the other indigo-dyed garments made by Miao artisans, RISD’s dosa Reissue travel coat looked weathered and fractured in appearance from the start, freed from expectations of perfection and thus open and accessible from its inception. Here the reference to armor does not imply imperviousness, but rather suggests how the coat might impart comfort while allowing for permeability and openness to one’s surroundings and to alternative histories.

In her book My Life with Things: The Consumer Diaries, anthropologist Elizabeth Chin writes about the power of the things we buy and use to prompt unexpected engagement with others: “Connectedness is also about relations between people, and I am interested as well in the ways that consumption and commodities serve as bridges between people in ways that may not be scary.”9 I have noticed that RISD students who have studied the coat at close range often seem to find that the raw materiality and fissures in its surface invite engagement on a personal level. This prompts me to wonder if the coat could also provoke the same care and attention within the civic and collective arenas. Might it inspire us as viewers to consider weathering as a starting place for recognizing the labor of making, care, and ultimately repair, while taking into account the value of the visible imprint of history and its scars?

Dosa’s travel coat serves as a reminder that worn garments are in a constant process of becoming, and are imbued with living histories that, if given the chance, may continue well beyond our time. The coat rejects mass production and limitless consumption; validates undervalued and repressed labor; and prompts a reimagined relationship to quality. It also provides a way of entering into and understanding objects as material and practice. In this way it offers alternative forms of social exchange, and thus, on many levels, serves as a creative act of repair.

- 1Elizabeth V. Spelman, Repair: The Impulse to Restore in a Fragile World (Boston: Beacon Press, 2003), 134.

- 2 Christina Kim, “Traveler 2014” on dosa’s website, https://dosainc.com/traveler-2014 (accessed April 29, 2018).

- 3Lorraine Wild, email message to the author, May 21, 2018.

- 4Sadae Torimaru and Tomoko Torimaru, Imprints on Cloth: Eighteen Years of Field Research among the Miao People of Guizhou, China (Fukuoka City, Japan: Akishige Tada Nishinippon Newspaper Co., 2005).

- 5Wild, email message, May 21, 2018.

- 6Torimaru and Torimaru, Imprints on Cloth, 20–22.

- 7Ibid., 30–31.

- 8Wild, email message, May 21, 2018.

- 9 Elizabeth Chin, My Life with Things: The Consumer Diaries (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016).