The sculpture Christ in the House of Simon the Pharisee (ca. 1500), which comes from Saint Michael’s Cathedral in Lendersdorf, Germany, depicts its characters’ emotions in immense detail. Simon’s wife, for example, looks either intensely bored or, alternatively, self-righteous—perhaps both at once. Of all the figures, though, none portrays as much emotion and character as Simon the Pharisee. Unlike the rest of the characters in the scene, who are, to an extent absorbed with the goings on beneath the table, Simon sits in his finery either eating with or, probably picking his teeth with what appears to be a bone. Though we may naively view Simon’s tooth-picking as typical for contemporary table manners, manuals from this time actually specified that picking the teeth at a meal was vulgar and should be avoided.1 This gesture, then, creates a sense of Simon as an explicitly negative and almost grotesque character. Though it is possible to argue that Simon, with his beautifully cut clothing, is portrayed in this sculpture as any irreligious wealthy German man, due to the state of contemporary Christian-Jewish relations it is most likely that Simon the Pharisee would have been considered a Jewish character.

Christ in the House of Simon the Pharisee was once part of the complexly decorated main altarpiece now reconstructed at Saint Michael’s Cathedral (above). The sculpture, in the top right-hand corner, occupied a small crevice of the altarpiece, which is centered round Christ’s admission of good and evil souls into heaven and hell. On the lower lefthand side of the image is a facsimile of the sculpture of Joachim and Anna (now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art) meeting at the Golden Gate after Joachim has been informed that they will finally have a child, and that this child will be the mother of God. The altarpiece, then, seems to emphasize the role of prayer, good deeds, forgiveness and judgment by combining scenes of deep emotion from the Christian tradition alongside one of the final judgment in the afterlife. As the work was a composite altarpiece and not originally intended as separate works, there is no record of each individual sculpture having a title, and the RISD title, Christ in the House of Simon the Pharisee, is retrospective. It is only retrospective, however, insofar as the title was not given by the artist in the way that we associate today with the title of a work. The title of the story in the gospel of Luke, however, was already entitled as such and it is therefore likely that the sculpture would have been referred to by the name Christ in the House of Simon the Pharisee long before it was officially christened so.

In the Biblical tale of this feast, Mary Magdalene enters Simon’s house while he is dining with Christ. Simon fails to recognize her spiritual status because of his prejudices. In response to this, Jesus shames him, pointing out how he has lacked kindness while hosting Christ. Simon had forgotten to offer Christ water with which to wash his feet, which is the very act that Mary Magdalene is performing here, almost in compensation for Simon’s mistreatment of Christ. This sculpture takes Christ’s criticism of Simon further, though, creating a caricature from which the viewer is meant to recoil and judge. Simon looks away with an expression that clearly communicates to the viewer that he does not regard Christ’s presence at his side as any special occurrence.

During the medieval period in Europe, the Pharisees of the New Testament were becoming increasingly synonymous with the Jewish people. In the time of Jesus there were several different groups of Jews. The primary group were the Pharisees, who made up the Sanhedrin or High Court of Jewish law.2 They were not the only Jewish group, though. The Sadducees, another denomination of Jews, worked at the Temple in Jerusalem as priests and held ritual, rather than judicial, power. They placed less stress on the strict law than the Pharisees and, when they did engage in discussions of the law, usually interpreted it differently. In his writings, Josephus also describes another, more ascetical group—the Essenes—though far less is known about them.3 In the fourth century, the Christian commentator and theologian Jerome was the first thinker to simplify this tripartite Judaism. In his commentary on the New Testament, Jerome argued that the official, accepted, mainstream Jewish people were the Pharisees while the other two groups held a sort of unofficial sectarian status.4 By the eleventh century, St. Anselm, directly inspired by Jerome, wrote that the term “Pharisee” was merely another name for the Jews and that the Biblical Pharisees were the direct ancestors of contemporary European Jewry.5 The theology of fifteenth-century Germany therefore encouraged contemporary viewers of this altarpiece to recognize Simon the Pharisee as Simon the Jew.

Notably, Simon dons a hat to go with his clothing. In contrast, Jesus’s head is uncovered, as is that of the unidentified third male figure in the composition, who leans forward towards the viewer, emphasizing his lack of head covering. Images of Jewish men had begun to include hats as a symbol of their Jewishness from the eleventh century, though there is little evidence to suggest this was based in any kind of real contemporary Jewish practice at first.6 By around 1150, the Jewish hat had become a recognizable and easily decipherable symbol of Jewishness in illuminated manuscripts.7 By the second half of the thirteenth century this idea spread from the artistic realm to that of German law, and Jews in Germany were required to wear a hat whenever they were leaving synagogue or taking an oath.8

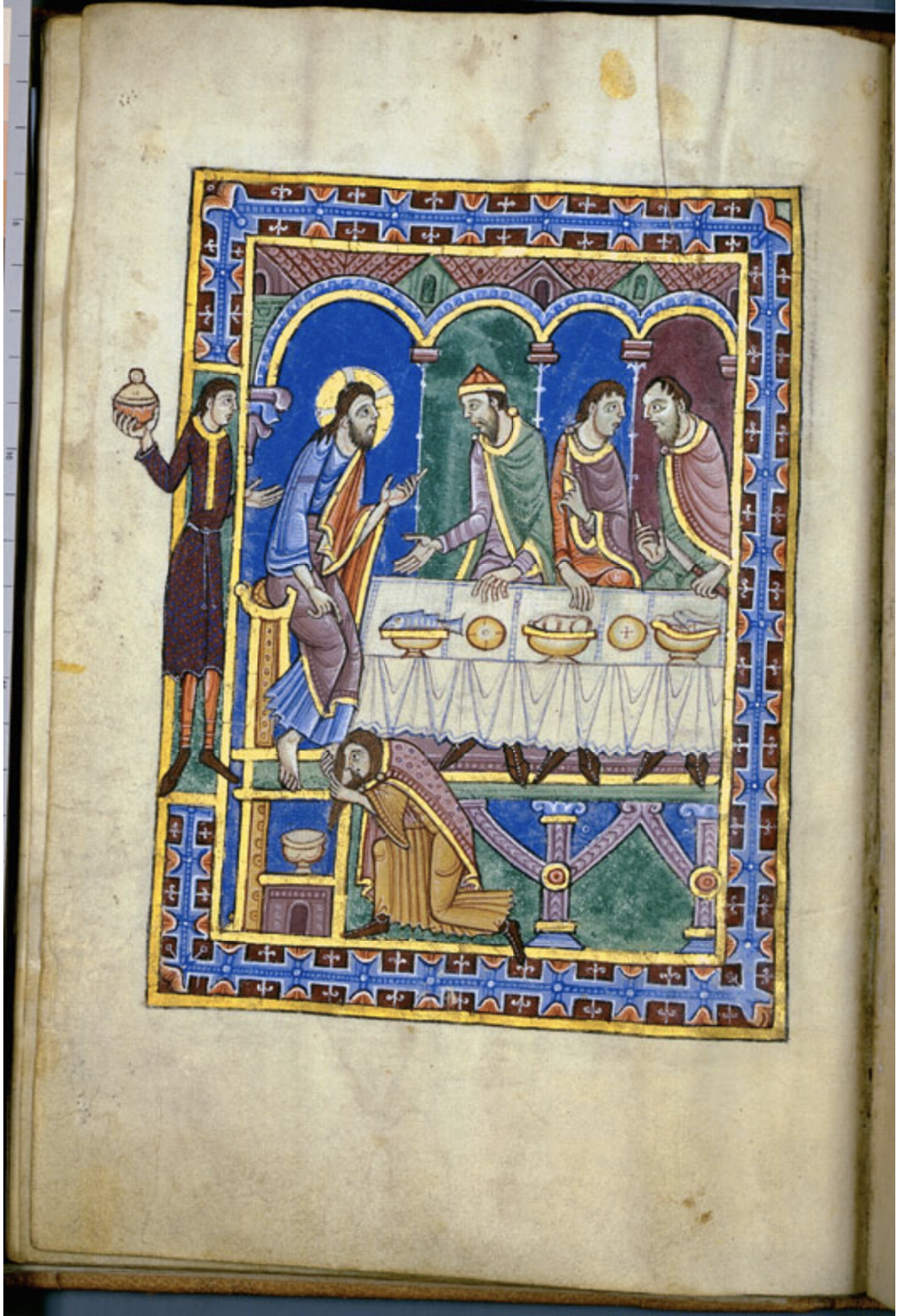

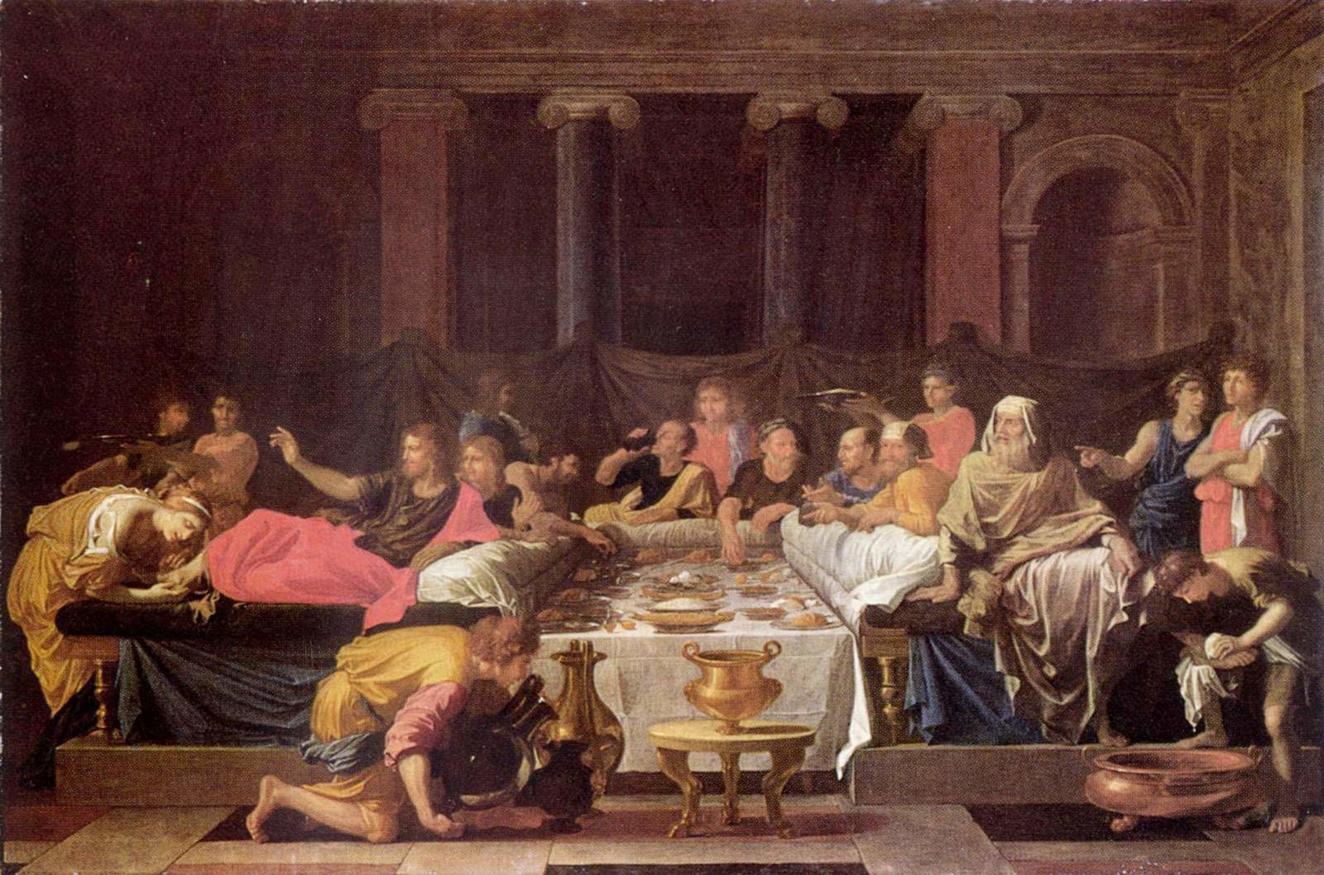

Prior depictions of Simon the Pharisee from elsewhere in Europe suggest that he had been thought of as a typically Jewish figure for several centuries before the RISD sculpture was created. In the twelfth century St. Albans Psalter, Simon’s hat stands as a clear marker of the Pharisee as a Jew (above). Like in the RISD sculpture, Simon is the only character wearing a hat indoors, confirming this as more than a fashionable accident. This tradition carries on all the way through to the seventeenth century, when Poussin showed Simon as a turban wearer in his painting Penance (below, Simon is the figure in the middle, next to Jesus). Therefore, while we have no direct testimony regarding contemporary responses and understanding of the figure of Simon in the sculpture, there is a strong case to be made that he would have been read, by default, as a Jew.

Michal Goldschmidt is a first-year PhD student in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture at Brown University. Her research interests include nineteenth- and twentieth-century Modernism and British art and empire.

- 1S. Gordon, Culinary Comedy in Medieval French Literature (West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 2007), 41.

- 2Jonathan Elukin, "Judaism: From Heresy to Pharisee in Early Medieval Christian Literature," Traditio 57 (2002): 49–50.

- 3Ibid., 51.

- 4Ibid., 56–57.

- 5Ibid., 64.

- 6S. Lipton, Dark Mirror: The Medieval Origins of Anti-Jewish Iconography (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2014), 16–24.

- 7Ibid.

- 8Ibid.