Video file

Image

The works relegated to museum storage have much to do with the ways art history has been written, who wrote it, and whom it serves. Those objects left unattended are ripe with stories to be told and opportunities for new ways of making. For Raid the Icebox Now, artists were invited to use the collection as an extension of their practice, to explore ideas they might otherwise not have pursued. Through access to a rich collection, material and financial resources, and a creative staff, new things have happened. The Raid the Icebox Now exhibitions and this digital publication are manifestations of this process.

Sarah Ganz Blythe is the RISD Museum's deputy director of exhibitions, education, and programs. She coordinated Raid the Icebox Now and supported the realization of the Pablo Helguera, Sebastian Ruth, and Triple Canopy projects for Raid the Icebox Now. Ganz Blythe's text explores the predicament of museum storage, the urgency it presents for accountability, and how the process of collaborating with artists allows new modalities to take shape.

Museums hold far more works of art than they are able to show. What is not selected to be on display in galleries lingers in storage. While some objects are made the heroes of art-historical narratives, others are given no role to play, and their stories remain mute. This has much to do with the ways in which the history of art has been written, who has written that history, and for whom it is told. Benjamin Zix’s fictive 1811 portrait of Baron Dominique-Vivant Denon positions the director of the Louvre among the artifacts that were assembled for the first public and encyclopedic museum. Known as the eye of Napoleon, Denon gathered up the spoils of war as the emperor conquered, weaving a story of power and domination. He justified this work in the name of Napoleon, preservation, and surrender: “Taken up at one and the same time with all genres of glory, the hero of our century, during the torment of war, required of our enemies trophies of peace, and he has seen to their conservation.”1 While the quantity and kinds of objects museums house have readily increased, the types of stories that are deemed worthy of telling have varied modestly from then to today. This means that for most institutions, storage abounds with the unseen and untold.

Ordered, labeled, and climate controlled, museum storage invites us to confront questions first posed by critic Edward Said and subsequently called up by Linda Tuhiwa Smith in Decolonizing Methodologies: “Who writes? For whom is the writing being done? In what circumstances? These . . . are the questions whose answers provide us with the ingredients making a politics of interpretation.”2 Through the works denied public view, storage tells us who has been doing the writing and for whom that writing has been done. To get behind the storage door is to intervene in the politics of interpretation. But if museums were conceived to reflect and reaffirm order, how can they begin to allocate value differently?

Image

Image

Benjamin Zix, Allegorical Portrait of Vivant Denon, 1811. Musée du Louvre, Paris.

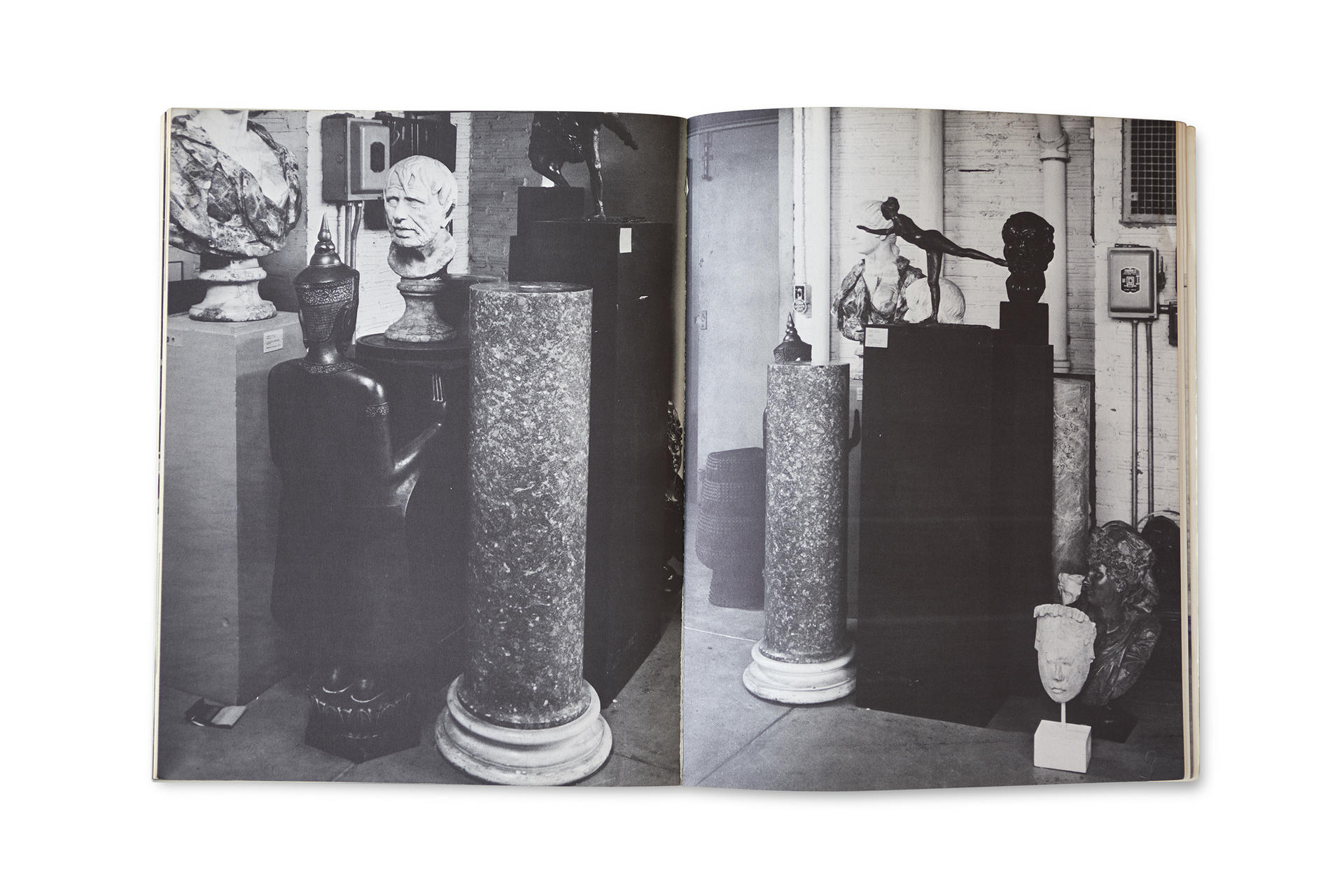

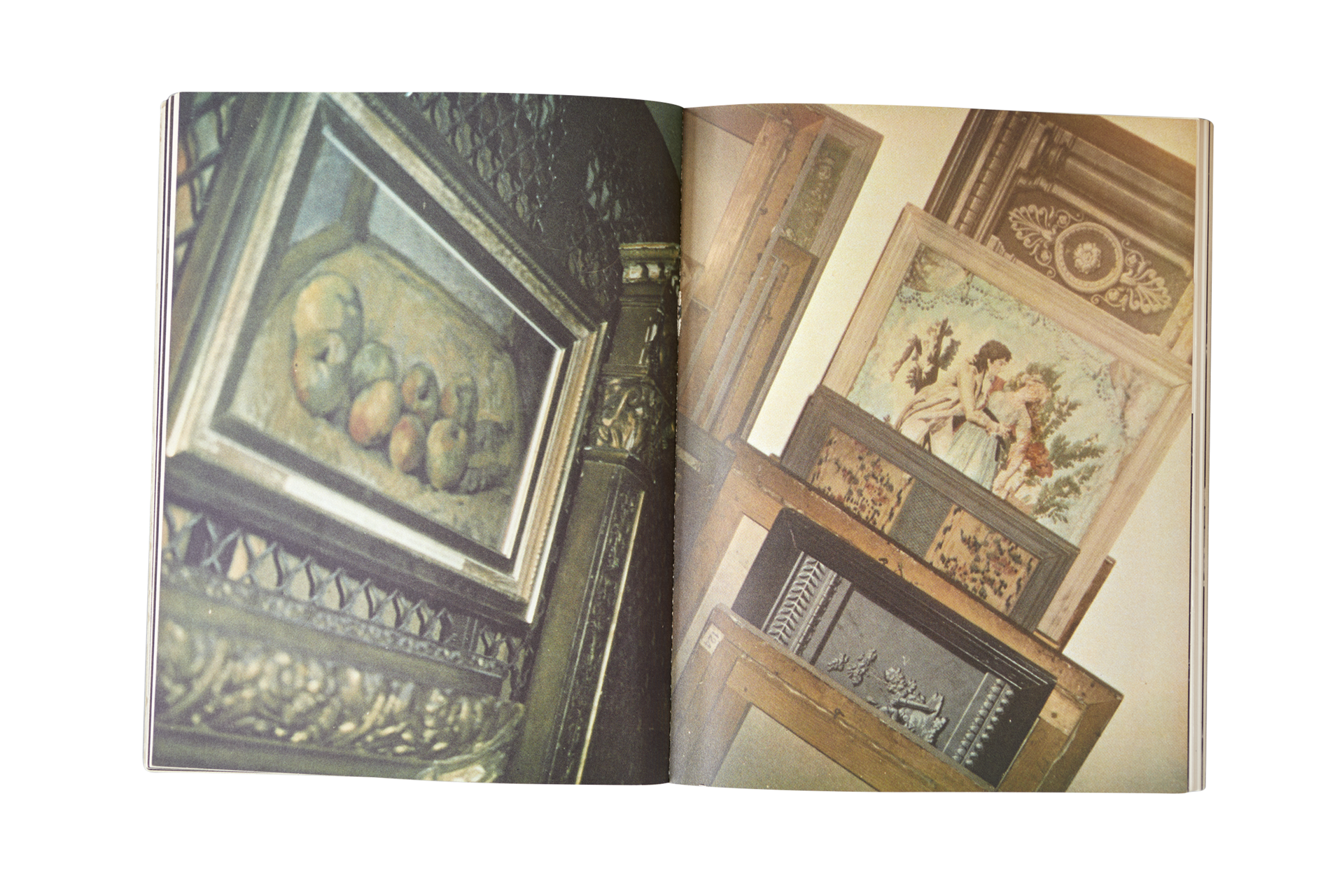

In 1969 Andy Warhol was invited to raid the storage of the RISD Museum. The hope was that he would reveal what was hiding there, attract the attention of disinterested art students, and connect a fairly conservative museum to contemporary-art practices. But Warhol did not create a new narrative that disrupted the canon—instead he laid bare the arbitrary nature of the museum’s collection itself. Victorian umbrellas, hatboxes, Windsor chairs, Navajo blankets, noteworthy and second-rate European paintings as well as the apparatuses of museum work, including storage cabinets, packing crates, and a forklift, sat side by side in the gallery, just as they had in storage. Like Denon working among the loot of the French empire, Warhol presented material in its uninterpreted, unordered state. By breaking from curatorial business as usual and replicating storage in the gallery, Warhol offered his eye through that of the institution. As one review noted, “Though Andy had not a single work of his own in the entire exhibition, the sum of his efforts at selection, placement and installation made up an entirely new creation: a walk-through, see-through, monumental work of Warholia.”3 His authorship was made blatantly evident in the naming of the exhibition, piercing the woefully misleading guise of neutrality that is standard museum practice.

Image

Image

Installation photograph of Raid the Icebox 1 with Andy Warhol, RISD Museum, 1970. Courtesy of RISD Archives.

Image

Installation photograph of Raid the Icebox 1 with Andy Warhol, RISD Museum, 1970. Courtesy of RISD Archives.

Image

Installation photograph of Raid the Icebox 1 with Andy Warhol, RISD Museum, 1970. Courtesy of RISD Archives.

Image

But the museum’s ambitions for this relatively radical gesture did not play out as intended. The opening featured a convergence of Providence elite, Warhol’s New York entourage, and protesting RISD students chanting “Sell the Exhibition” and “People Not Porcelain” while holding out cans to solicit donations for financial aid. Despite casting off typical museum decorum, the exhibition came off as tone deaf to the social and cultural movements that characterized the Vietnam War era, which included Black Power, Chicano rights, women’s liberation, and gay rights. Indeed, Warhol’s institutionally sanctioned, albeit unexpected, gestures pale in critical force next to the protests, intervisions, and petitions concurrently waged by artists against the ways that politics, money, racism, and sexism manifested in museums.4

Image

Video file

Student-produced newspaper-style flyer, calling attention to the paucity of financial aid for lower-income students and the fact that very few minority students were enrolled at RISD, April 1970. The flyer was distributed at the press conference for the opening of Raid the Icebox I with Andy Warhol. Courtesy of RISD Archives.

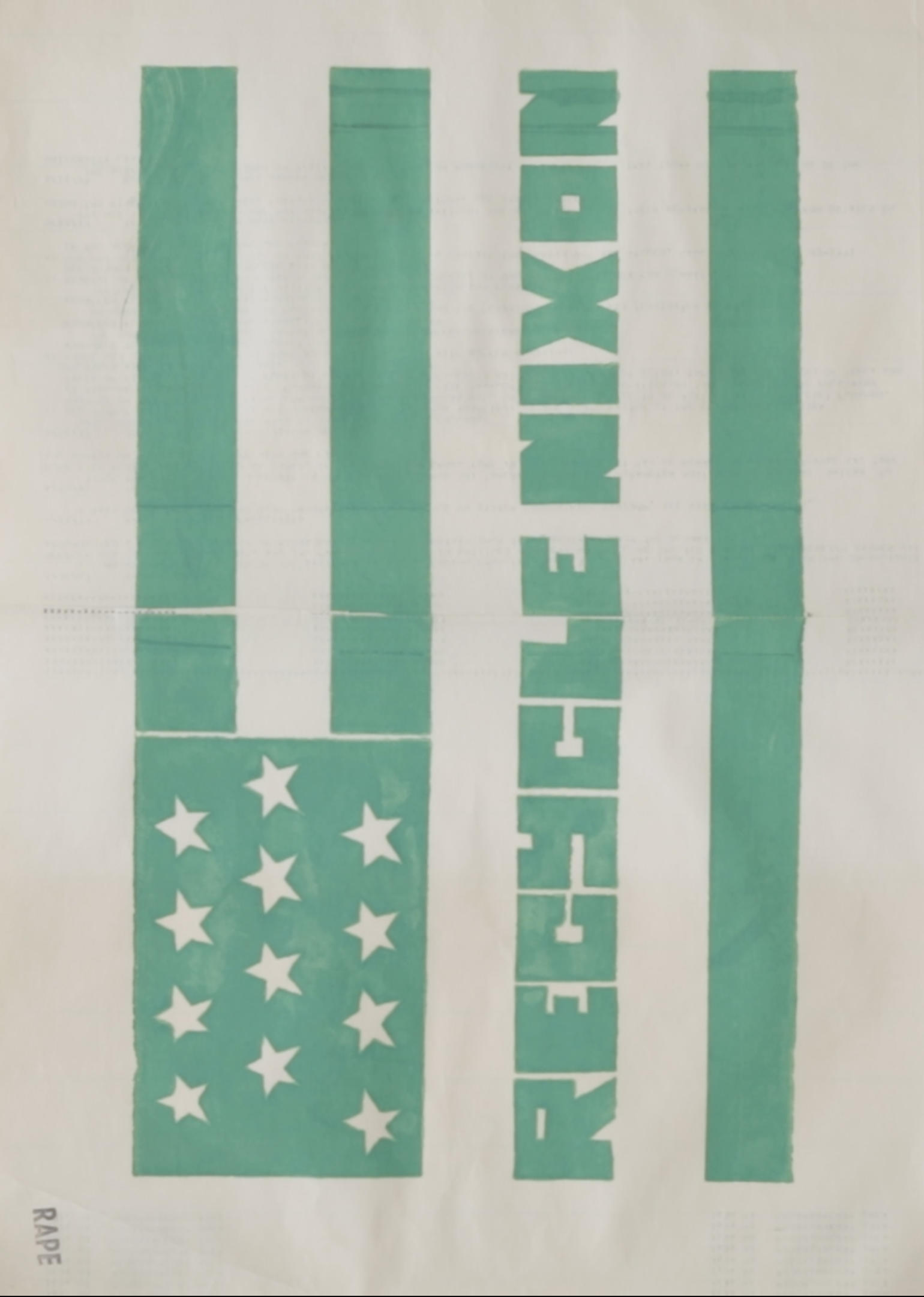

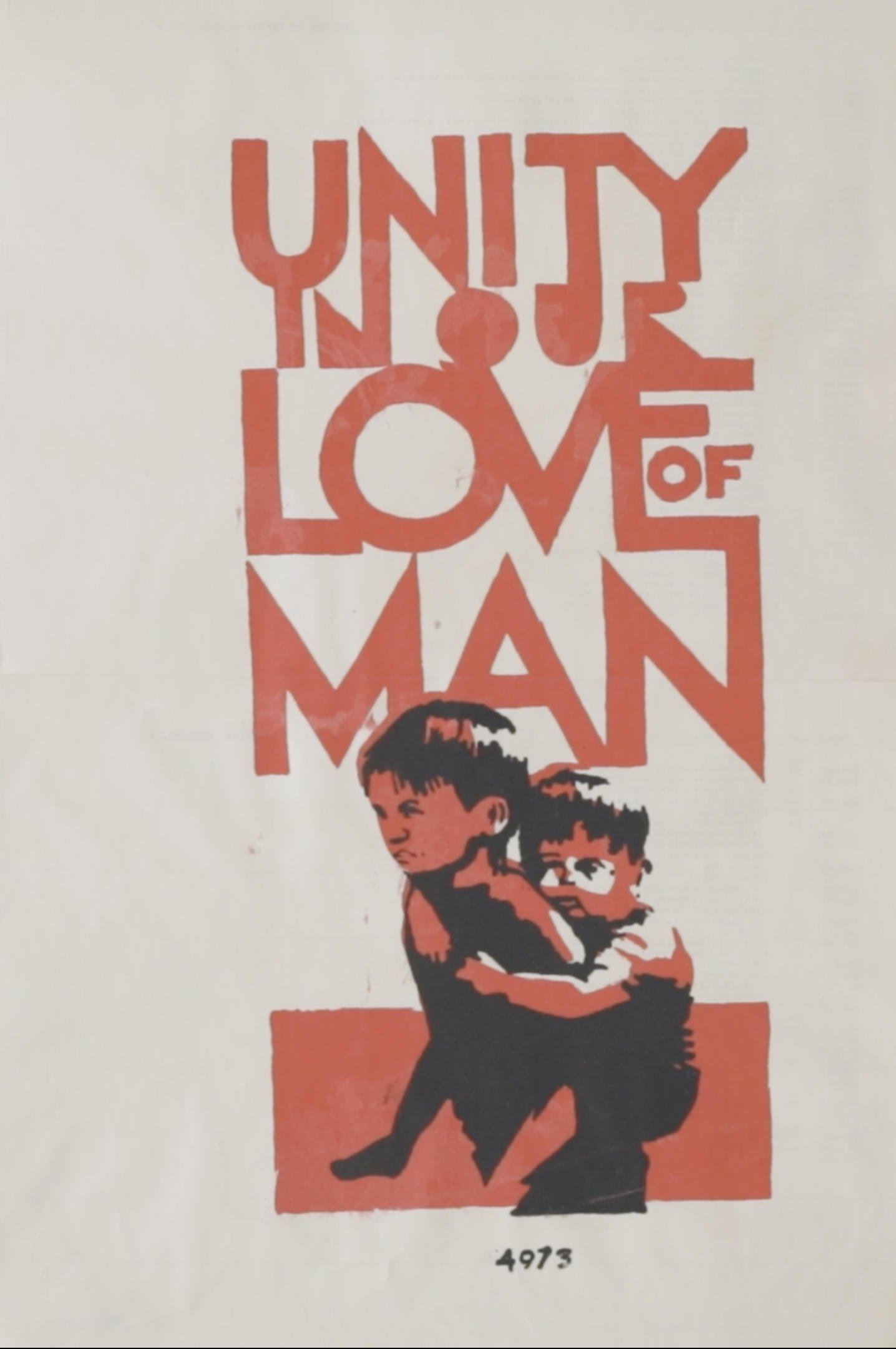

Image

Silk-screened political protest posters designed and printed by RISD students during the suspension of classes and the nationwide strike following the U.S. expansion of the Vietnam War into Cambodia and the Kent State University deaths at the hands of the Ohio National Guard on May 4, 1970. Courtesy of RISD Archives.

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Yet the invitation made by the RISD Museum, and Warhol’s unexpected approach, has been written into art history as an early manifestation of institutional critique. Black and white photos of Raid the Icebox are now ubiquitous in curatorial literature. Umbrellas hanging bat-like from the ceiling, Windsor chairs scaling the gallery wall, and sandbags holding up paintings suggest a moment of rupture.5 Reflecting on the legacy of the exhibition at a convening held in advance of this project, scholar and curator Ingrid Schaffner described it as an “expression of institutional freedom as well for artists, for curators, for museums. . . . As a curator, there’s always a couple exhibitions you’d like to go back [to], little loopholes in time, and have experienced. And this has always been one of mine.”6 Perhaps the ticket to this institutional freedom is individual authorship, which is more often afforded to artists than to curators obliged to speak with and for the institution.

The accompanying catalogue, now out of print, has become a prized object in itself. Hastily assembled to Warhol’s specifications, it includes the Polaroids Warhol shot at oblique angles during his visits, printed “big, grainy, informal.”7 A checklist of the exhibition organized by type of object—Baskets, Paintings, Sculpture, Parasols and Umbrellas—is accompanied by captions transcribed directly from card-catalogue entries, including secondary, sometimes incorrect information contained there that was not first offered up for curatorial review.

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Image

Video file

Image

Anniversaries are opportunities for celebration, but also for reflection and new considerations of accountability. Fifty years after Raid the Icebox 1 with Andy Warhol, RISD Museum storage remains full of the unseen and untold. And while collaborations with artists have been a mainstay, not unlike the gambit of the artist-as-curator, the impact of these collaborations has been intense but not transformative. As Fred Wilson observed reflecting on Mining the Museum at the Maryland Historical Society in 1994, “Museums present culture and can present bias at the same time. . . . If the galleries are the face of the museum, the offices are the brain, and the storage is the unconscious. The manner-controlled and aestheticized public galleries belie the haphazard, chaotic, and sometimes ugly private spaces hidden from view.”8

Just as Denon collected and organized looted artifacts in support of Napoleon’s empire, the presentation of culture is always the presentation of bias, which is more often than not white and privileged, economically and otherwise. The fiftieth anniversary of Raid the Icebox has been an opportunity for the RISD Museum staff to push against this state of affairs by trying new approaches. Collaborating artists were selected for the ways in which working with the museum’s collection and staff might allow for mutual growth. In keeping with RISD’s mission as a museum and an art school, these artists were invited to interact with the collection as an extension of their studio and practice and to use this space to do work and explore ideas they otherwise would not have the time or opportunity to pursue. While exhibition-making is a significant manifestation of Raid the Icebox Now, the multiyear engagement with and commitment to research processes, relationships, and experimentation was of equal if not greater value. Giving these artists access to a rich collection, material and financial resources, and a creative staff has allowed new things to happen. What these things fully mean, and how they will continue to change our ways of working, we still don’t know.

This publication has been built in response to involving the artists in a collaborative process that has allowed the form to be guided by the content. While each project followed a different path, each was initially guided by a shared prompt to the artists: what would you like to make that you haven’t made before? What would you like to do that you wouldn’t do otherwise? As we considered these questions as an institution and a staff, it allowed us to work into the idea of the museum not as an inevitable, but rather as a temporary and malleable framework for new narratives, areas of knowledge, and relationships to grow.

Image

- Baron Dominique-Vivant Denon, quoted by Peter Brooks, “Napoleon’s Eye,” New York Review of Books, November 19, 2019, https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2009/11/19/napoleons-eye/.

- Linda Tuhiwa Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (New York: Zed Books, 2012), 86.

- Trevor Wyatt Moree, “The Midnight Snack of Andy Warhol,” The Christian Century, April 1, 1970: 396–97.

- See Hans Haacke’s project in MoMA’s Information show; the Art Workers’ Coalition (AWC), founded in New York in 1969; and the New York Art Strike Against Racism, War, and Repression, founded in 1970.

- See Deborah Bright, “Shopping the Leftovers: Warhol’s Collecting Strategies in Raid the Icebox I,” Art History 24, no. 2 (April 2001): 281. See also Anthony Huberman, “Andy Warhol, Raid the Icebox I with Andy Warhol, 1969,” The Artist As Curator 7, Mousse 48 (2014): 1–20.

- Ingrid Schaffner, Raid the Icebox Now Convening, held at the RISD Museum June 20, 2018. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1hCtkepw0KddGtVqD0lD6qmFY8vDCFFmWZc9….

- Letter from Stephen Ostrow to David Bourdon, July 30, 1969, Raid the Icebox with Andy Warhol, Box 1 of 2, RISD Archives.

- Fred Wilson, Raid the Icebox Now Convening, RISD Museum, June 20, 2018. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1hCtkepw0KddGtVqD0lD6qmFY8vDCFFmWZc9…

Cite this article as

Chicago Style

MLA Style

Shareable Link

Copy this page's URL to your clipboard.

This chapter was created under the direction of Sarah Ganz Blythe and accompanies the exhibition Raid the Icebox Now, on view at the RISD Museum September 13, 2019–September 6, 2020. Authored by Sarah Ganz Blythe. Creative direction by Carolyn Gennari. Design by Brendan Campbell. Additional production support by Carson Evans, Arielle Eisen, Erik Gould, and Jeremy Radtke.

Our understanding of Andy Warhol's project and RISD at that time was made possible through the rich holdings of RISD Archives and the support of Andrew Martinez and Douglas Doe.