Now one of the preeminent schools of art and design in the world, RISD was a small but ambitious institution when it was established in 1877. Among its many purposes was “the general advancement of public art education by the exhibition of works of art.” The concurrent establishment of the RISD Museum was not incidental; the educational work of the Museum was inherent in the mission of the school from its inception. In 2014, the Museum’s Education Department employs 11 dedicated staff members, assisted by 35 volunteer docents. This year also marks 100 years of the docent program’s invaluable work with K–12 students.

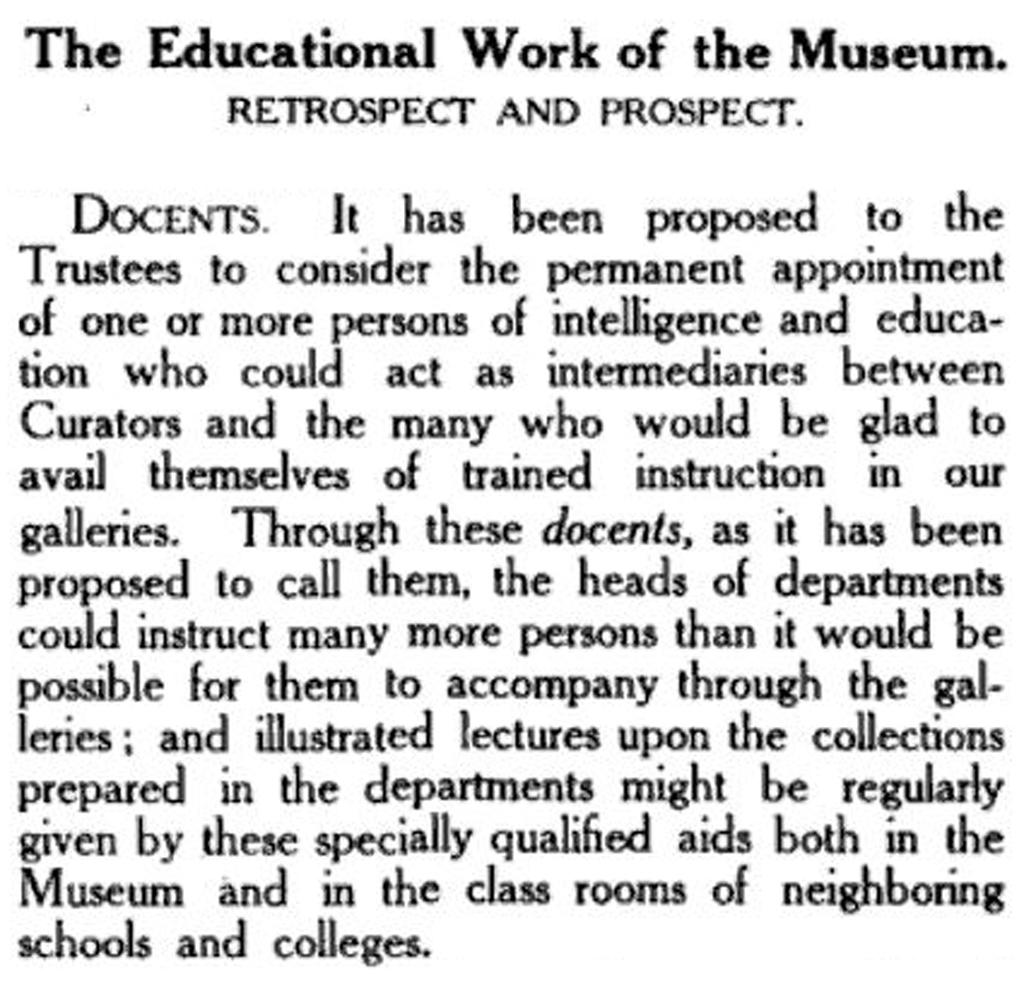

Although the Museum was indispensable to the education of RISD students from its earliest days, its efforts in educating the public were less commendable, and it was far from unique in this regard. It was not until the early 20th century that museum professionals began serious discussions about their responsibility toward the education of the general public. Public programs were infrequent and almost exclusively restricted to curatorial lectures. One of the earliest and most frequently cited public commitments to education was in the June 1906 Bulletin of the MFA Boston, in which that museum coined the term “docent.”

Coincidentally, one of the first docents the MFA employed to provide these public gallery talks was L. Earle Rowe, who would later become president of RISD. Upon his appointment as director of RISD and the Museum in 1912, he initiated a similar program, with the objective of “offer[ing] every inducement to the thinking citizen to bring him to a more complete and helpful conception of the universal application of art to the problems of the present day.” Initially limited to a series of Sunday gallery lectures, docent service at this time was provided by local scholars, artists, and RISD Museum staff. One of the first docent lectures was given by local arts leader Sydney Richmond Burleigh, whose work is now in the Museum’s collection.

The RISD Museum docents’ engagement with the public was expanded in 1914 to encompass work with local schools. The January 1914 edition of the Bulletin describes the coordination of one-hour visits by each elementary school class in the Providence Public School District. The majority of the work was done by one docent, Margery Mackillop. After graduating from Wellesley College in 1912, Mackillop first began work as the museum assistant, and was soon charged with leading all school visits.

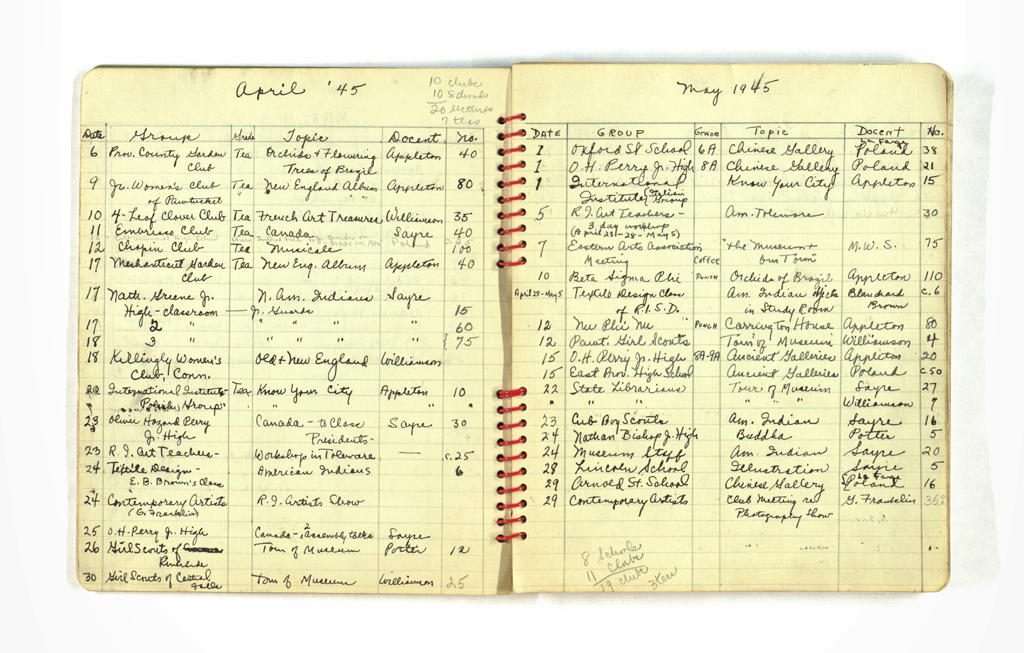

Although the education of the public was included in the Museum’s mission throughout Rowe’s tenure, it was not until Alexander Dorner was appointed director in 1938 that a dedicated Education Department was established. Carolyn MacDonald became the department’s first curator in 1940. In her 1944 thesis at Columbia University’s Teachers College, she described the previous efforts of Museum staff as “haphazard” and lamented the lack of trained docents and the fact that the Providence Public School Department, questioning curricular relevance and dissatisfied with Museum guidance, was considering withdrawing their support of school visits. MacDonald reinvigorated programming and worked with the new superintendent of Providence public schools to develop a systematic program in which two-thirds of junior high students visited the Museum regularly as a part of their social studies curriculum. A student teacher assisted the Museum with educational programming, and MacDonald also put a heavy emphasis on the development of teacher resources, helping educators incorporate the Museum in their classroom teaching. Members of the Junior League of Providence had been volunteering at the Museum in other capacities, and MacDonald offered them a docent training course, creating the first team of docents in the current sense of the word, meaning volunteer gallery educators who work alongside professional museum education staff. MacDonald built a roster of 28 part-time volunteer docents, as well as program assistants, including parents, social workers, and college students. In 1944, Carolyn MacDonald wrote, “Two men—factory workers—hearing what we were doing, volunteered to help on Sundays partly out of interest for the educational possibilities for underprivileged children (“if only there had been something like this when I was a kid!”) and partly to meet the charming young docents. The Education Department needed help, and was not averse to abetting romance to get it.” In the same report, she added, “Our child volunteers must not go without mention. A group of boys came regularly after school and got so familiar with Museum objects that we were happy to include them as junior docents.”

During the Second World War, the gas shortage prevented school buses from bringing students to the Museum. This may have contributed to the expansion of circulation programs begun by MacDonald. Between the 1940s and the 1990s, the Museum provided schools with “exhibitions” of 2- and 3-dimensional reproductions, and Education Department staff also gave classroom lectures. In 1946 a young woman named Pearl Nathan, having recently moved to Providence from New York City, became a docent. Although the Education Department was still very small, the Museum’s school visit program was continuing to grow, and Nathan’s responsibilities included organizing and giving tours to all students enrolled at Providence’s Catholic schools. In 2014, at the age of 100, Nathan remains involved in the docent program at the RISD Museum.

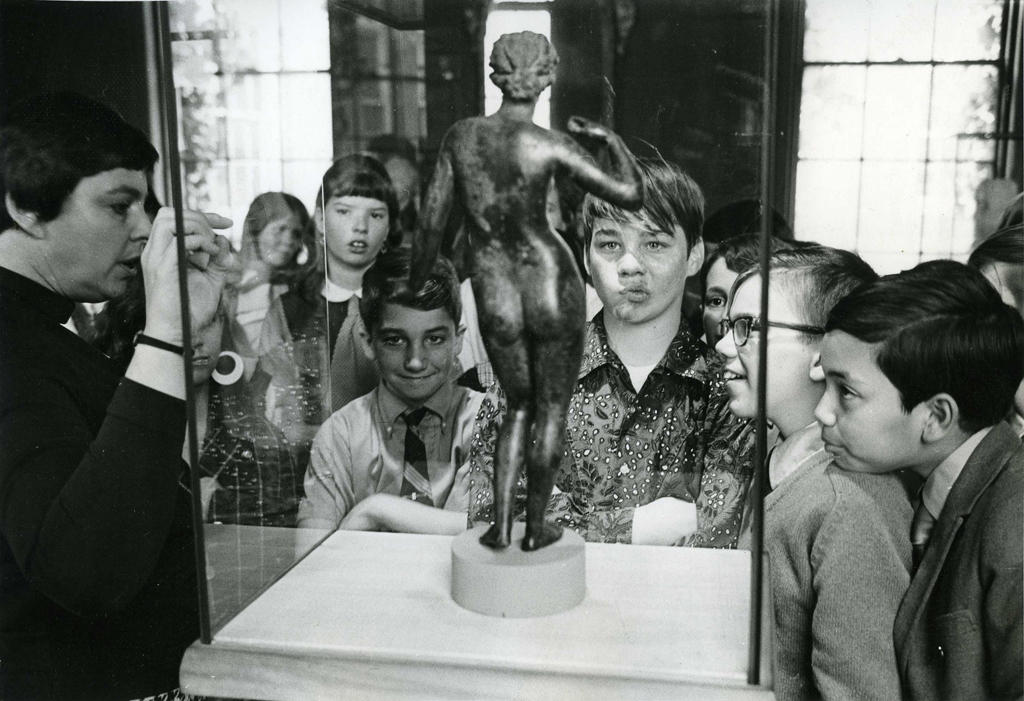

By the mid-1950s the department had a set schedule of visits for 4th- through 9th-graders in the Providence, Cranston, and Warwick school districts, most of which were led by Betty Woodhouse, the director of education, and one full-time gallery teacher. The docent program as it exists today began to take shape in the late 1950s and was firmly established by the early 1960s. Increased numbers of professional staff resulted in an expansion of services and the training of more volunteers. With active recruitment and the inception of a docent training course, the department had at least 25 docents by 1965.

While visits by classes from Providence Public Schools are now taught by professional museum educators and include customized lessons and classroom pre-visits, the Museum still relies on its docent corps to facilitate thoughtful, relevant, and inspiring visits for more than 4000 K–12 students every year.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

MacDonald, Carolyn Ethel. Museum Resources for Teachers: The Report of a Type A Project. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University, 1944

RISD Corporation Committee Records, 1910–1920. RISD Archives.

Education Department Reports, April 1951–April 1964. RISD Archives.

“Procedure for Docents Taking Tours,” n.d. (ca. 1960s). RISD Archives.

Nathan, Pearl. Interview by Kathleen Munro, March 2013.

RISD Museum Docents, Cooking with Art: Favorite Recipes of the RISD Museum Docents. Providence, 2006.

Wellesley College, The Wellesley Legenda 1912, Book 10.

Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts, Volumes 2–7. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1904.

Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design, Volumes I-XXVI. Providence: Rhode Island School of Design, 1913-1938.

Bulletin of the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, volumes XXVI-XXIX. Providence: Rhode Island School of Design, c1938-1942.

Rhode Island School of Design, Museum of Art. Museum Notes, volumes 1-83. Providence: Rhode Island School of Design, Museum of Art, 1943-1996.

Alexandra Poterack

Program Coordinator