Inventing Impressionism

Introduction

In the spring of 1874, a group of French artists seeking an alternative to official juried shows mounted an exhibition of their work in a rented studio in Paris. A critic, provoked by a painting that Claude Monet entitled Impression: Sunrise, called their effort an “Exhibition of Impressionists.” Intended to underscore a lack of serious content, “impressionist” also implied the abandonment of established academic practice, but it came to represent the original ways in which these men and women captured modern life.

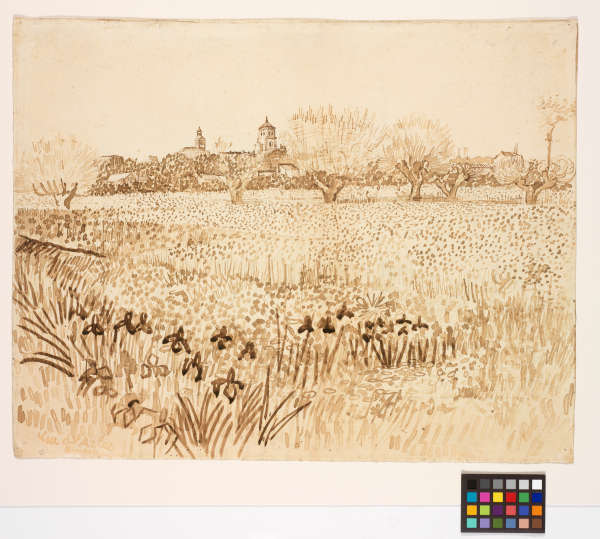

Embracing the term impressionist, the artists organized eight group exhibitions over the next twelve years, showing paintings that depicted leisure activities, domestic and social encounters, urban parks and avenues, and fleeting moments in nature. Often working outside the studio, these artists sketched in theaters and cafés and painted in fields and along riverbanks. Their shared compositional strategies included cropped points of view and flattened perspectives that evoked a sense of immediacy. Many painted directly on white grounds, using unmixed pigments and complementary hues to render bright sunlight or atmospheric effects.

At the same time, artists working in impressionist styles devised highly individualized strategies of painting and drawing. Monet mimicked the physical properties and sensations he observed. Camille Pissarro assembled landscapes with dense patterns of brushstrokes; Cézanne modeled forms with flat patches of color; Berthe Morisot used ribbon-like gestures to register movement. Edgar Degas drew figures from every angle before placing them in a composition. Their innovations overturned long-held preconceptions of realist representation and defined a new way of seeing the world around them.

Britany Salsbury, Maureen O'Brien