Pacific Islands Tapa Cloth

Introduction

As early as the sixth century B.C., trees of the Moraceae family were used to produce a bark cloth in Asia. The preferred species, Broussonetia papyrifera or paper mulberry was later introduced into the Pacific islands, particularly Polynesia where the art of decorated bark cloth, tapa, flourished. Known as "siapo" in Samoa or "ahu" in Tahiti, the present term was most likely derived from the Hawaiian word "kapa" (pronounced "tapa") meaning "the beaten." Tapa, a prized commodity, was the chief item of trade amongst the islanders and with Western explorers. By the late 19th century, there was a sharp decline in tapa production, though islands like Samoa continued its manufacture for export trade.

The production of bark cloth was a lengthy process involving the entire community. Men harvested the paper mulberry trees, stripping the bark from trees and soaking it in water. With grooved wooden beaters, the women would pound the pulp which would soften and expand it several inches, knitting the fibers together resulting in a thready woven appearance. Several strips of bark cloth were pasted together with arrowroot to make a stronger tapa or beaten, slightly overlapped, to make wider pieces.

Once dried, dyes prepared from primarily vegetable sources would be applied in elaborate patterns that spoke of an island's creative style. Often commented on in expedition journals, the most spectacular color was a brilliant red obtained by combining two plants which alone had no tendency toward red (Cordia sebestena and Ficus tinctoria). Yellow dye made from ground turmeric or from the nono bush, Morinda citrifolia, was often used to stain an entire tapa as a foundation color. Mountain plaintain produced purple, and for black the tapa was submerged in the mud of a taro swamp for days and then dried.

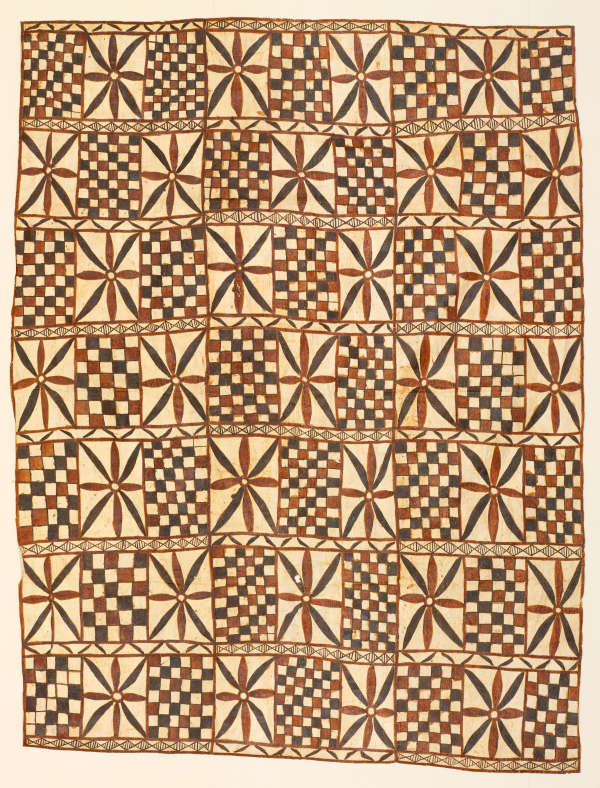

Dyes were also stamped, stenciled, rubbed, and painted on freehand. Carved bamboo was used for small repeat designs and woodblocks for larger designs. Detailed tablets were made with pandanus leaves and coconut leaf midribs, placed under the tapa, then rubbed with a dye saturated cloth. Burnt candlenut or the roasted nut kernels of Aleurites moluccana were rubbed in, creating thick dark dividing lines or large circles. This tablet process was favored in Samoa, Tonga, and Fiji, and fine examples are displayed in this exhibition. In Hawaii, plants, particularly ferns, were dipped into the dyes and pressed onto the cloth leaving behind a delicate natural pattern.

The finest quality tapa was reserved for tribal chief's clothing or for use in ceremonies; however islanders had a variety of common uses such as everyday garments, room dividers, or the traditional sleeping sheet known as "tapa moe". Tapa kites were popular with most of the Polynesian tribes, tapa turbans in Fiji, and black tapa shrouds in Hawaii. Very thin tapa was used as mosquito screening or bandages, and very coarse tapa saved for rope or wicks. It was the combination of dye patterns beautifully designed and the delicate texture of the most finely beaten bark cloth, that created a superior tapa.