Error message

- Warning: Undefined array key 0 in Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances() (line 388 of modules/contrib/footnotes/src/Plugin/Filter/FootnotesFilter.php).

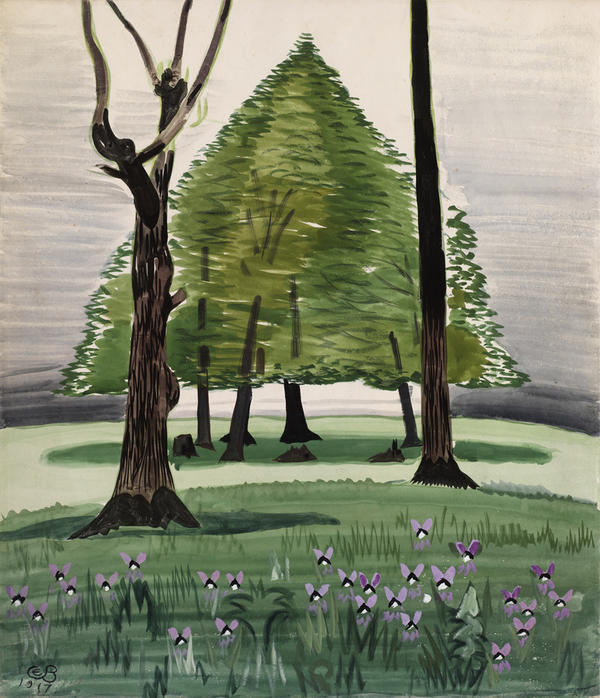

Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances('In the January 1920 <em>Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design,</em> RISD Museum director L. Earle Rowe drew attention to the recent acquisition of a colonial American portrait by the British-trained painter L. Earle Rowe, “Portrait of Theodore Atkinson, Jr. by Joseph Blackburn.” Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design, January 1920, VIII, 2–4. Ill. p. 1.. The elegant likeness of young Theodore Atkinson, Jr. (fig. 1), was sold to the museum by a descendant of Atkinson’s mother, Hannah, who with her husband, Theodore Sr., was painted by Blackburn in 1760 (figs. 2 and 3). The parents’ selection of the eminent Blackburn suited their station in life: Hannah was the sister of Benning Wentworth, governor of the province of New Hampshire from 1741 until 1767. Theodore Atkinson, Sr., served as president of the Council of New Hampshire, secretary and chief justice of the colony, and delegate to the Albany Congress. In the 1750s, Blackburn had brought English Rococo style to the sober tradition of American portraiture, and his emphasis on depicting luxurious textiles reinforced his popularity with patrons in Bermuda, Newport, Boston, and Portland, New Hampshire, where the Atkinson family flourished. In contrast to their refined and sober depictions, their son’s livelier image seemed to celebrate the energy and promise of the next generation. Vibrantly colored and meticulously drawn, it represented the twenty-one-year-old Harvard College graduate as if poised to assume his place in the world. The portrait became known as one of Blackburn’s most distinguished works and in 1911 was among a select group of paintings chosen to represent the artist in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Catalogue of an Exhibition of Colonial Portraits: November 6 To December 31, 1911 (1911), no. 2, Theodore Atkinson, Jr., by Joseph B. Blackburn. In 1762, young Atkinson married his pretty young cousin, Frances Deering Wentworth, and subsequently commissioned John Singleton Copley to paint her portrait (Fig. 4). The newlyweds settled in Portsmouth, where Atkinson drew income from land grants and followed a preordained career path in which he served as secretary of the province of New Hampshire, member of His Majesty’s council, and collector of customs. His youthful momentum was tragically cut short in 1769 when he died of consumption at the age of thirty-two. After a notoriously short period of mourning, Frances married John Wentworth, a cousin with strong Tory sympathies, and fled with him to England before the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. By the early twentieth century, the four Atkinson portraits had been separated from one another. Around 1918–1919, the portraits of the colonel and his wife found homes in museums in Worcester, Massachusetts, and Cleveland, Ohio, and Theodore Jr.’s came to Rhode Island. The image of Frances Deering Atkinson had left the fold earlier, and in 1876 entered the New York Public Library by way of the James Lenox collection. (Sold by the library in 2005, her portrait now resides at the Crystal Bridges Museum in Bentonville, Arkansas.) When the younger couple’s likenesses were reunited at the 1911 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, no one seemed to have remarked that the strong color and crisp draftsmanship that characterized the wife’s portrait by Copley were also evident in Theodore’s, or noticed their shared distinctive contrast to the muted tones and simplified construction of the other Blackburn portraits nearby. In New York, the <em>Portrait of Theodore Atkinson, Jr.,</em> continued to signal the older artist’s best and most accomplished work, a position that was reinforced when it was featured as the frontispiece of Lawrence Park’s 1923 monograph <em>Joseph Blackburn: A Colonial Portrait Painter</em>. Art historians are trained to determine the authenticity of works of art by studying their style, construction, and physical appearances, and by documenting their living history and chain of ownership. There was no doubt when the portrait of Theodore Atkinson, Jr., was acquired by RISD that it had descended in an unbroken family succession along with Blackburn’s signed portraits of his parents. Reputable scholars had published it as Blackburn’s work, and although there was no evidence of a signature, this was not uncommon in colonial portraiture. And yet, Earle Rowe was careful to note that the unknowns associated with relatively recent colonial art history were not unlike the challenges faced by Renaissance scholars. He mentioned a lack of documentary evidence about the “shadowy personalities and period of activity” of American artists, admitting that at present “the greatest mystery and fascination surrounds Blackburn, whose work had such a great influence on Copley,” and whose paintings had frequently been ascribed to the younger artist. In this case, Rowe had good reason to be cautious, as the long existence of the younger Atkinson portrait among the Blackburn portraits may have led to attribution by association. Theodore Jr.’s premature death, his wife’s remarriage, and the earlier dispersion of her portrait may have obscured obvious clues to the artist’s identity, for in fact, the 1757–1758 commission for his portrait was executed by Blackburn’s brilliant young follower from Boston: the twenty-year-old John Singleton Copley. The confusion over authorship endured until 1943, when in conjunction with the exhibition <em>New England Painting, 1700</em>–<em>1775</em>, held at the Worcester Art Museum, the American art historian and dealer William Sawitzky argued that the “sculptural form, solidity, linear precision and marmoreal flesh tones are closer to Copley than to Blackburn’s weaker formal sense and greater reliance on chromatic and tonal quality, even allowing for the influence that the precocious Copley exercised on his older English-trained colleague.”“News and Comments,” Magazine of Art 36 (Mar. 1943), p. 115. According to the March 1943 “News and Comments” column of <em>Magazine of Art</em>, Anne Allison, Charles K. Bolton, Louisa Dresser, Henry Wilder Foote, John Hill Morgan, Mrs. Haven Parker, and other experts in attendance agreed, and the portrait was assigned to Copley. Although the circumstances of Copley’s introduction to the Atkinsons are not known, they may have seen his portraits of the Reverend Arthur Browne’s family in Portsmouth, or become aware of the portraits Copley had painted of prominent Bostonians in poses identical to the one later chosen for their son.Janet L. Comey in Carrie Rebora and Paul Staiti, et al., John Singleton Copley in America (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, distributed by Harry N. Abrams, 1995), pp. 178–81, comprehensively analyzed Atkinson’s portrait and identified the similarly posed portraits of Joshua Winslow, 1755 (Santa Barbara Museum of Art) and William Brattle, 1756 (Harvard University Art Museums). She also noted the Atkinsons’ connections to the family of Reverend Arthur Browne of Queen’s Chapel, Copley’s earlier patrons in Portsmouth. Although barely twenty when he painted young Atkinson, Copley demonstrated immense skills in drawing and color, and astutely mined mezzotint portraits of English aristocrats for aspects of pose, setting, and costume.See Trevor Fairbrother, “John Singleton Copley’s Use of British Mezzotints for His American Portraits: A Reappraisal Prompted by New Discoveries,” Arts 55 (Mar. 1981), pp. 122–30. He had learned the techniques of painting by studying the works of other artists who practiced in Boston, including its leading portraitist, John Smibert, but his most dramatic advances took place around 1755 with the arrival in Boston of the English painter Blackburn. By 1758 he had perfected the most distinctive aspects of Blackburn’s manner, including the depiction of fine clothing and mastery of narrative-enhancing poses. Applying these skills to Atkinson’s portrait, he seamlessly incorporated the scion’s aristocratic appearance into the fiction of a young English lord striding forward to survey his country estate. Atkinson’s slender figure virtually inhabited the aggrandizing <em>contrapposto</em> stance with the grace of a dancer. His costume was likely virtual as well, as “invented dress” based on a variety of continental prototypes was common for both male and female portraits in the eighteenth century.Copley’s depiction of both male and female costume is discussed in Aileen Ribeiro‘s “‘The Whole Art of Dress’: Costume in the Work of John Singleton Copley,” in Rebora and Staiti, et al., pp. 103–15. Copley chose to dress Atkinson in a muted salmon coat with deep boot cuffs and matching tight breeches, lavishing attention on his padded silk waistcoat. In a device lifted from contemporary British portraiture, Copley tucked Atkinson’s left hand into his trouser pocket, effectively emphasizing the vest’s silver embroidery and flaunting both its considerable expense and his own genius at rendering sumptuous textiles. Absent from this staging are the classical ruins or attributes of learning so often present in Grand Tour portraits of young British aristocrats. Atkinson’s landscape is pristine and has yet to be imbued with his accomplishments. Instead, evident and intertwined in the Copley portrait of Atkinson are the rising careers of two promising young American men. The combined effects of likeness, costume, and verdant acreage were enough to signal Atkinson’s distinguished pedigree and brilliant future. At the same time, they trumpeted Copley’s own precocious arrival, and his ability to convey personality and social status with skills that surpassed those of any other painter in the colonies, including the much-admired Joseph Blackburn, who unintentionally in the twentieth century wore the laurels of his youthful follower’s acclaim. <strong>Maureen C. O’Brien</strong> <strong>Curator of Painting and Sculpture</strong> ') (Line: 116) Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->process('In the January 1920 <em>Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design,</em> RISD Museum director L. Earle Rowe drew attention to the recent acquisition of a colonial American portrait by the British-trained painter L. Earle Rowe, “Portrait of Theodore Atkinson, Jr. by Joseph Blackburn.” Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design, January 1920, VIII, 2–4. Ill. p. 1.. The elegant likeness of young Theodore Atkinson, Jr. (fig. 1), was sold to the museum by a descendant of Atkinson’s mother, Hannah, who with her husband, Theodore Sr., was painted by Blackburn in 1760 (figs. 2 and 3). The parents’ selection of the eminent Blackburn suited their station in life: Hannah was the sister of Benning Wentworth, governor of the province of New Hampshire from 1741 until 1767. Theodore Atkinson, Sr., served as president of the Council of New Hampshire, secretary and chief justice of the colony, and delegate to the Albany Congress. In the 1750s, Blackburn had brought English Rococo style to the sober tradition of American portraiture, and his emphasis on depicting luxurious textiles reinforced his popularity with patrons in Bermuda, Newport, Boston, and Portland, New Hampshire, where the Atkinson family flourished. In contrast to their refined and sober depictions, their son’s livelier image seemed to celebrate the energy and promise of the next generation. Vibrantly colored and meticulously drawn, it represented the twenty-one-year-old Harvard College graduate as if poised to assume his place in the world. The portrait became known as one of Blackburn’s most distinguished works and in 1911 was among a select group of paintings chosen to represent the artist in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Catalogue of an Exhibition of Colonial Portraits: November 6 To December 31, 1911 (1911), no. 2, Theodore Atkinson, Jr., by Joseph B. Blackburn. In 1762, young Atkinson married his pretty young cousin, Frances Deering Wentworth, and subsequently commissioned John Singleton Copley to paint her portrait (Fig. 4). The newlyweds settled in Portsmouth, where Atkinson drew income from land grants and followed a preordained career path in which he served as secretary of the province of New Hampshire, member of His Majesty’s council, and collector of customs. His youthful momentum was tragically cut short in 1769 when he died of consumption at the age of thirty-two. After a notoriously short period of mourning, Frances married John Wentworth, a cousin with strong Tory sympathies, and fled with him to England before the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. By the early twentieth century, the four Atkinson portraits had been separated from one another. Around 1918–1919, the portraits of the colonel and his wife found homes in museums in Worcester, Massachusetts, and Cleveland, Ohio, and Theodore Jr.’s came to Rhode Island. The image of Frances Deering Atkinson had left the fold earlier, and in 1876 entered the New York Public Library by way of the James Lenox collection. (Sold by the library in 2005, her portrait now resides at the Crystal Bridges Museum in Bentonville, Arkansas.) When the younger couple’s likenesses were reunited at the 1911 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, no one seemed to have remarked that the strong color and crisp draftsmanship that characterized the wife’s portrait by Copley were also evident in Theodore’s, or noticed their shared distinctive contrast to the muted tones and simplified construction of the other Blackburn portraits nearby. In New York, the <em>Portrait of Theodore Atkinson, Jr.,</em> continued to signal the older artist’s best and most accomplished work, a position that was reinforced when it was featured as the frontispiece of Lawrence Park’s 1923 monograph <em>Joseph Blackburn: A Colonial Portrait Painter</em>. Art historians are trained to determine the authenticity of works of art by studying their style, construction, and physical appearances, and by documenting their living history and chain of ownership. There was no doubt when the portrait of Theodore Atkinson, Jr., was acquired by RISD that it had descended in an unbroken family succession along with Blackburn’s signed portraits of his parents. Reputable scholars had published it as Blackburn’s work, and although there was no evidence of a signature, this was not uncommon in colonial portraiture. And yet, Earle Rowe was careful to note that the unknowns associated with relatively recent colonial art history were not unlike the challenges faced by Renaissance scholars. He mentioned a lack of documentary evidence about the “shadowy personalities and period of activity” of American artists, admitting that at present “the greatest mystery and fascination surrounds Blackburn, whose work had such a great influence on Copley,” and whose paintings had frequently been ascribed to the younger artist. In this case, Rowe had good reason to be cautious, as the long existence of the younger Atkinson portrait among the Blackburn portraits may have led to attribution by association. Theodore Jr.’s premature death, his wife’s remarriage, and the earlier dispersion of her portrait may have obscured obvious clues to the artist’s identity, for in fact, the 1757–1758 commission for his portrait was executed by Blackburn’s brilliant young follower from Boston: the twenty-year-old John Singleton Copley. The confusion over authorship endured until 1943, when in conjunction with the exhibition <em>New England Painting, 1700</em>–<em>1775</em>, held at the Worcester Art Museum, the American art historian and dealer William Sawitzky argued that the “sculptural form, solidity, linear precision and marmoreal flesh tones are closer to Copley than to Blackburn’s weaker formal sense and greater reliance on chromatic and tonal quality, even allowing for the influence that the precocious Copley exercised on his older English-trained colleague.”“News and Comments,” Magazine of Art 36 (Mar. 1943), p. 115. According to the March 1943 “News and Comments” column of <em>Magazine of Art</em>, Anne Allison, Charles K. Bolton, Louisa Dresser, Henry Wilder Foote, John Hill Morgan, Mrs. Haven Parker, and other experts in attendance agreed, and the portrait was assigned to Copley. Although the circumstances of Copley’s introduction to the Atkinsons are not known, they may have seen his portraits of the Reverend Arthur Browne’s family in Portsmouth, or become aware of the portraits Copley had painted of prominent Bostonians in poses identical to the one later chosen for their son.Janet L. Comey in Carrie Rebora and Paul Staiti, et al., John Singleton Copley in America (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, distributed by Harry N. Abrams, 1995), pp. 178–81, comprehensively analyzed Atkinson’s portrait and identified the similarly posed portraits of Joshua Winslow, 1755 (Santa Barbara Museum of Art) and William Brattle, 1756 (Harvard University Art Museums). She also noted the Atkinsons’ connections to the family of Reverend Arthur Browne of Queen’s Chapel, Copley’s earlier patrons in Portsmouth. Although barely twenty when he painted young Atkinson, Copley demonstrated immense skills in drawing and color, and astutely mined mezzotint portraits of English aristocrats for aspects of pose, setting, and costume.See Trevor Fairbrother, “John Singleton Copley’s Use of British Mezzotints for His American Portraits: A Reappraisal Prompted by New Discoveries,” Arts 55 (Mar. 1981), pp. 122–30. He had learned the techniques of painting by studying the works of other artists who practiced in Boston, including its leading portraitist, John Smibert, but his most dramatic advances took place around 1755 with the arrival in Boston of the English painter Blackburn. By 1758 he had perfected the most distinctive aspects of Blackburn’s manner, including the depiction of fine clothing and mastery of narrative-enhancing poses. Applying these skills to Atkinson’s portrait, he seamlessly incorporated the scion’s aristocratic appearance into the fiction of a young English lord striding forward to survey his country estate. Atkinson’s slender figure virtually inhabited the aggrandizing <em>contrapposto</em> stance with the grace of a dancer. His costume was likely virtual as well, as “invented dress” based on a variety of continental prototypes was common for both male and female portraits in the eighteenth century.Copley’s depiction of both male and female costume is discussed in Aileen Ribeiro‘s “‘The Whole Art of Dress’: Costume in the Work of John Singleton Copley,” in Rebora and Staiti, et al., pp. 103–15. Copley chose to dress Atkinson in a muted salmon coat with deep boot cuffs and matching tight breeches, lavishing attention on his padded silk waistcoat. In a device lifted from contemporary British portraiture, Copley tucked Atkinson’s left hand into his trouser pocket, effectively emphasizing the vest’s silver embroidery and flaunting both its considerable expense and his own genius at rendering sumptuous textiles. Absent from this staging are the classical ruins or attributes of learning so often present in Grand Tour portraits of young British aristocrats. Atkinson’s landscape is pristine and has yet to be imbued with his accomplishments. Instead, evident and intertwined in the Copley portrait of Atkinson are the rising careers of two promising young American men. The combined effects of likeness, costume, and verdant acreage were enough to signal Atkinson’s distinguished pedigree and brilliant future. At the same time, they trumpeted Copley’s own precocious arrival, and his ability to convey personality and social status with skills that surpassed those of any other painter in the colonies, including the much-admired Joseph Blackburn, who unintentionally in the twentieth century wore the laurels of his youthful follower’s acclaim. <strong>Maureen C. O’Brien</strong> <strong>Curator of Painting and Sculpture</strong> ', 'en') (Line: 118) Drupal\filter\Element\ProcessedText::preRenderText(Array) call_user_func_array(Array, Array) (Line: 111) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doTrustedCallback(Array, Array, 'Render #pre_render callbacks must be methods of a class that implements \Drupal\Core\Security\TrustedCallbackInterface or be an anonymous function. The callback was %s. See https://www.drupal.org/node/2966725', 'exception', 'Drupal\Core\Render\Element\RenderCallbackInterface') (Line: 797) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doCallback('#pre_render', Array, Array) (Line: 386) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 106) __TwigTemplate_4039b6d648e4a30fc59604b38849a688->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 46) __TwigTemplate_d1494d795b4bd5366283e85f3e7729dc->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 43) __TwigTemplate_253b62141ad73ee07345b0067cf59829->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/contrib/classy/templates/field/field--text-with-summary.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('field', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 231) __TwigTemplate_d0a4e06ec4cdc862487a9e59e7ee55e6->block_node_content(Array, Array) (Line: 171) Twig\Template->displayBlock('node_content', Array, Array) (Line: 91) __TwigTemplate_fb45c12c057c90d6dad87acc3f8af627->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 51) __TwigTemplate_d0a4e06ec4cdc862487a9e59e7ee55e6->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/content/node--teaser.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('node', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 60) __TwigTemplate_b5820ae2fc9ac809d8bb920432eaa798->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/contrib/classy/templates/views/views-view-unformatted.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('views_view_unformatted', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 129) __TwigTemplate_c1babb60e112ad993125dc5af5a5b779->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/views/views-view--site-search--page-1.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('views_view__site_search__page_1', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array, ) (Line: 238) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\{closure}() (Line: 592) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->executeInRenderContext(Object, Object) (Line: 239) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->prepare(Array, Object, Object) (Line: 128) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->renderResponse(Array, Object, Object) (Line: 90) Drupal\Core\EventSubscriber\MainContentViewSubscriber->onViewRenderArray(Object, 'kernel.view', Object) call_user_func(Array, Object, 'kernel.view', Object) (Line: 111) Drupal\Component\EventDispatcher\ContainerAwareEventDispatcher->dispatch(Object, 'kernel.view') (Line: 186) Symfony\Component\HttpKernel\HttpKernel->handleRaw(Object, 1) (Line: 76) Symfony\Component\HttpKernel\HttpKernel->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 58) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\Session->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 48) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\KernelPreHandle->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 191) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->fetch(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 128) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->lookup(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 82) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 270) Drupal\shield\ShieldMiddleware->bypass(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 137) Drupal\shield\ShieldMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 48) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\ReverseProxyMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 51) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\NegotiationMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 51) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\StackedHttpKernel->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 704) Drupal\Core\DrupalKernel->handle(Object) (Line: 19) - Warning: Undefined array key 0 in Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances() (line 389 of modules/contrib/footnotes/src/Plugin/Filter/FootnotesFilter.php).

Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances('In the January 1920 <em>Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design,</em> RISD Museum director L. Earle Rowe drew attention to the recent acquisition of a colonial American portrait by the British-trained painter L. Earle Rowe, “Portrait of Theodore Atkinson, Jr. by Joseph Blackburn.” Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design, January 1920, VIII, 2–4. Ill. p. 1.. The elegant likeness of young Theodore Atkinson, Jr. (fig. 1), was sold to the museum by a descendant of Atkinson’s mother, Hannah, who with her husband, Theodore Sr., was painted by Blackburn in 1760 (figs. 2 and 3). The parents’ selection of the eminent Blackburn suited their station in life: Hannah was the sister of Benning Wentworth, governor of the province of New Hampshire from 1741 until 1767. Theodore Atkinson, Sr., served as president of the Council of New Hampshire, secretary and chief justice of the colony, and delegate to the Albany Congress. In the 1750s, Blackburn had brought English Rococo style to the sober tradition of American portraiture, and his emphasis on depicting luxurious textiles reinforced his popularity with patrons in Bermuda, Newport, Boston, and Portland, New Hampshire, where the Atkinson family flourished. In contrast to their refined and sober depictions, their son’s livelier image seemed to celebrate the energy and promise of the next generation. Vibrantly colored and meticulously drawn, it represented the twenty-one-year-old Harvard College graduate as if poised to assume his place in the world. The portrait became known as one of Blackburn’s most distinguished works and in 1911 was among a select group of paintings chosen to represent the artist in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Catalogue of an Exhibition of Colonial Portraits: November 6 To December 31, 1911 (1911), no. 2, Theodore Atkinson, Jr., by Joseph B. Blackburn. In 1762, young Atkinson married his pretty young cousin, Frances Deering Wentworth, and subsequently commissioned John Singleton Copley to paint her portrait (Fig. 4). The newlyweds settled in Portsmouth, where Atkinson drew income from land grants and followed a preordained career path in which he served as secretary of the province of New Hampshire, member of His Majesty’s council, and collector of customs. His youthful momentum was tragically cut short in 1769 when he died of consumption at the age of thirty-two. After a notoriously short period of mourning, Frances married John Wentworth, a cousin with strong Tory sympathies, and fled with him to England before the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. By the early twentieth century, the four Atkinson portraits had been separated from one another. Around 1918–1919, the portraits of the colonel and his wife found homes in museums in Worcester, Massachusetts, and Cleveland, Ohio, and Theodore Jr.’s came to Rhode Island. The image of Frances Deering Atkinson had left the fold earlier, and in 1876 entered the New York Public Library by way of the James Lenox collection. (Sold by the library in 2005, her portrait now resides at the Crystal Bridges Museum in Bentonville, Arkansas.) When the younger couple’s likenesses were reunited at the 1911 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, no one seemed to have remarked that the strong color and crisp draftsmanship that characterized the wife’s portrait by Copley were also evident in Theodore’s, or noticed their shared distinctive contrast to the muted tones and simplified construction of the other Blackburn portraits nearby. In New York, the <em>Portrait of Theodore Atkinson, Jr.,</em> continued to signal the older artist’s best and most accomplished work, a position that was reinforced when it was featured as the frontispiece of Lawrence Park’s 1923 monograph <em>Joseph Blackburn: A Colonial Portrait Painter</em>. Art historians are trained to determine the authenticity of works of art by studying their style, construction, and physical appearances, and by documenting their living history and chain of ownership. There was no doubt when the portrait of Theodore Atkinson, Jr., was acquired by RISD that it had descended in an unbroken family succession along with Blackburn’s signed portraits of his parents. Reputable scholars had published it as Blackburn’s work, and although there was no evidence of a signature, this was not uncommon in colonial portraiture. And yet, Earle Rowe was careful to note that the unknowns associated with relatively recent colonial art history were not unlike the challenges faced by Renaissance scholars. He mentioned a lack of documentary evidence about the “shadowy personalities and period of activity” of American artists, admitting that at present “the greatest mystery and fascination surrounds Blackburn, whose work had such a great influence on Copley,” and whose paintings had frequently been ascribed to the younger artist. In this case, Rowe had good reason to be cautious, as the long existence of the younger Atkinson portrait among the Blackburn portraits may have led to attribution by association. Theodore Jr.’s premature death, his wife’s remarriage, and the earlier dispersion of her portrait may have obscured obvious clues to the artist’s identity, for in fact, the 1757–1758 commission for his portrait was executed by Blackburn’s brilliant young follower from Boston: the twenty-year-old John Singleton Copley. The confusion over authorship endured until 1943, when in conjunction with the exhibition <em>New England Painting, 1700</em>–<em>1775</em>, held at the Worcester Art Museum, the American art historian and dealer William Sawitzky argued that the “sculptural form, solidity, linear precision and marmoreal flesh tones are closer to Copley than to Blackburn’s weaker formal sense and greater reliance on chromatic and tonal quality, even allowing for the influence that the precocious Copley exercised on his older English-trained colleague.”“News and Comments,” Magazine of Art 36 (Mar. 1943), p. 115. According to the March 1943 “News and Comments” column of <em>Magazine of Art</em>, Anne Allison, Charles K. Bolton, Louisa Dresser, Henry Wilder Foote, John Hill Morgan, Mrs. Haven Parker, and other experts in attendance agreed, and the portrait was assigned to Copley. Although the circumstances of Copley’s introduction to the Atkinsons are not known, they may have seen his portraits of the Reverend Arthur Browne’s family in Portsmouth, or become aware of the portraits Copley had painted of prominent Bostonians in poses identical to the one later chosen for their son.Janet L. Comey in Carrie Rebora and Paul Staiti, et al., John Singleton Copley in America (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, distributed by Harry N. Abrams, 1995), pp. 178–81, comprehensively analyzed Atkinson’s portrait and identified the similarly posed portraits of Joshua Winslow, 1755 (Santa Barbara Museum of Art) and William Brattle, 1756 (Harvard University Art Museums). She also noted the Atkinsons’ connections to the family of Reverend Arthur Browne of Queen’s Chapel, Copley’s earlier patrons in Portsmouth. Although barely twenty when he painted young Atkinson, Copley demonstrated immense skills in drawing and color, and astutely mined mezzotint portraits of English aristocrats for aspects of pose, setting, and costume.See Trevor Fairbrother, “John Singleton Copley’s Use of British Mezzotints for His American Portraits: A Reappraisal Prompted by New Discoveries,” Arts 55 (Mar. 1981), pp. 122–30. He had learned the techniques of painting by studying the works of other artists who practiced in Boston, including its leading portraitist, John Smibert, but his most dramatic advances took place around 1755 with the arrival in Boston of the English painter Blackburn. By 1758 he had perfected the most distinctive aspects of Blackburn’s manner, including the depiction of fine clothing and mastery of narrative-enhancing poses. Applying these skills to Atkinson’s portrait, he seamlessly incorporated the scion’s aristocratic appearance into the fiction of a young English lord striding forward to survey his country estate. Atkinson’s slender figure virtually inhabited the aggrandizing <em>contrapposto</em> stance with the grace of a dancer. His costume was likely virtual as well, as “invented dress” based on a variety of continental prototypes was common for both male and female portraits in the eighteenth century.Copley’s depiction of both male and female costume is discussed in Aileen Ribeiro‘s “‘The Whole Art of Dress’: Costume in the Work of John Singleton Copley,” in Rebora and Staiti, et al., pp. 103–15. Copley chose to dress Atkinson in a muted salmon coat with deep boot cuffs and matching tight breeches, lavishing attention on his padded silk waistcoat. In a device lifted from contemporary British portraiture, Copley tucked Atkinson’s left hand into his trouser pocket, effectively emphasizing the vest’s silver embroidery and flaunting both its considerable expense and his own genius at rendering sumptuous textiles. Absent from this staging are the classical ruins or attributes of learning so often present in Grand Tour portraits of young British aristocrats. Atkinson’s landscape is pristine and has yet to be imbued with his accomplishments. Instead, evident and intertwined in the Copley portrait of Atkinson are the rising careers of two promising young American men. The combined effects of likeness, costume, and verdant acreage were enough to signal Atkinson’s distinguished pedigree and brilliant future. At the same time, they trumpeted Copley’s own precocious arrival, and his ability to convey personality and social status with skills that surpassed those of any other painter in the colonies, including the much-admired Joseph Blackburn, who unintentionally in the twentieth century wore the laurels of his youthful follower’s acclaim. <strong>Maureen C. O’Brien</strong> <strong>Curator of Painting and Sculpture</strong> ') (Line: 116) Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->process('In the January 1920 <em>Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design,</em> RISD Museum director L. Earle Rowe drew attention to the recent acquisition of a colonial American portrait by the British-trained painter L. Earle Rowe, “Portrait of Theodore Atkinson, Jr. by Joseph Blackburn.” Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design, January 1920, VIII, 2–4. Ill. p. 1.. The elegant likeness of young Theodore Atkinson, Jr. (fig. 1), was sold to the museum by a descendant of Atkinson’s mother, Hannah, who with her husband, Theodore Sr., was painted by Blackburn in 1760 (figs. 2 and 3). The parents’ selection of the eminent Blackburn suited their station in life: Hannah was the sister of Benning Wentworth, governor of the province of New Hampshire from 1741 until 1767. Theodore Atkinson, Sr., served as president of the Council of New Hampshire, secretary and chief justice of the colony, and delegate to the Albany Congress. In the 1750s, Blackburn had brought English Rococo style to the sober tradition of American portraiture, and his emphasis on depicting luxurious textiles reinforced his popularity with patrons in Bermuda, Newport, Boston, and Portland, New Hampshire, where the Atkinson family flourished. In contrast to their refined and sober depictions, their son’s livelier image seemed to celebrate the energy and promise of the next generation. Vibrantly colored and meticulously drawn, it represented the twenty-one-year-old Harvard College graduate as if poised to assume his place in the world. The portrait became known as one of Blackburn’s most distinguished works and in 1911 was among a select group of paintings chosen to represent the artist in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Catalogue of an Exhibition of Colonial Portraits: November 6 To December 31, 1911 (1911), no. 2, Theodore Atkinson, Jr., by Joseph B. Blackburn. In 1762, young Atkinson married his pretty young cousin, Frances Deering Wentworth, and subsequently commissioned John Singleton Copley to paint her portrait (Fig. 4). The newlyweds settled in Portsmouth, where Atkinson drew income from land grants and followed a preordained career path in which he served as secretary of the province of New Hampshire, member of His Majesty’s council, and collector of customs. His youthful momentum was tragically cut short in 1769 when he died of consumption at the age of thirty-two. After a notoriously short period of mourning, Frances married John Wentworth, a cousin with strong Tory sympathies, and fled with him to England before the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. By the early twentieth century, the four Atkinson portraits had been separated from one another. Around 1918–1919, the portraits of the colonel and his wife found homes in museums in Worcester, Massachusetts, and Cleveland, Ohio, and Theodore Jr.’s came to Rhode Island. The image of Frances Deering Atkinson had left the fold earlier, and in 1876 entered the New York Public Library by way of the James Lenox collection. (Sold by the library in 2005, her portrait now resides at the Crystal Bridges Museum in Bentonville, Arkansas.) When the younger couple’s likenesses were reunited at the 1911 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, no one seemed to have remarked that the strong color and crisp draftsmanship that characterized the wife’s portrait by Copley were also evident in Theodore’s, or noticed their shared distinctive contrast to the muted tones and simplified construction of the other Blackburn portraits nearby. In New York, the <em>Portrait of Theodore Atkinson, Jr.,</em> continued to signal the older artist’s best and most accomplished work, a position that was reinforced when it was featured as the frontispiece of Lawrence Park’s 1923 monograph <em>Joseph Blackburn: A Colonial Portrait Painter</em>. Art historians are trained to determine the authenticity of works of art by studying their style, construction, and physical appearances, and by documenting their living history and chain of ownership. There was no doubt when the portrait of Theodore Atkinson, Jr., was acquired by RISD that it had descended in an unbroken family succession along with Blackburn’s signed portraits of his parents. Reputable scholars had published it as Blackburn’s work, and although there was no evidence of a signature, this was not uncommon in colonial portraiture. And yet, Earle Rowe was careful to note that the unknowns associated with relatively recent colonial art history were not unlike the challenges faced by Renaissance scholars. He mentioned a lack of documentary evidence about the “shadowy personalities and period of activity” of American artists, admitting that at present “the greatest mystery and fascination surrounds Blackburn, whose work had such a great influence on Copley,” and whose paintings had frequently been ascribed to the younger artist. In this case, Rowe had good reason to be cautious, as the long existence of the younger Atkinson portrait among the Blackburn portraits may have led to attribution by association. Theodore Jr.’s premature death, his wife’s remarriage, and the earlier dispersion of her portrait may have obscured obvious clues to the artist’s identity, for in fact, the 1757–1758 commission for his portrait was executed by Blackburn’s brilliant young follower from Boston: the twenty-year-old John Singleton Copley. The confusion over authorship endured until 1943, when in conjunction with the exhibition <em>New England Painting, 1700</em>–<em>1775</em>, held at the Worcester Art Museum, the American art historian and dealer William Sawitzky argued that the “sculptural form, solidity, linear precision and marmoreal flesh tones are closer to Copley than to Blackburn’s weaker formal sense and greater reliance on chromatic and tonal quality, even allowing for the influence that the precocious Copley exercised on his older English-trained colleague.”“News and Comments,” Magazine of Art 36 (Mar. 1943), p. 115. According to the March 1943 “News and Comments” column of <em>Magazine of Art</em>, Anne Allison, Charles K. Bolton, Louisa Dresser, Henry Wilder Foote, John Hill Morgan, Mrs. Haven Parker, and other experts in attendance agreed, and the portrait was assigned to Copley. Although the circumstances of Copley’s introduction to the Atkinsons are not known, they may have seen his portraits of the Reverend Arthur Browne’s family in Portsmouth, or become aware of the portraits Copley had painted of prominent Bostonians in poses identical to the one later chosen for their son.Janet L. Comey in Carrie Rebora and Paul Staiti, et al., John Singleton Copley in America (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, distributed by Harry N. Abrams, 1995), pp. 178–81, comprehensively analyzed Atkinson’s portrait and identified the similarly posed portraits of Joshua Winslow, 1755 (Santa Barbara Museum of Art) and William Brattle, 1756 (Harvard University Art Museums). She also noted the Atkinsons’ connections to the family of Reverend Arthur Browne of Queen’s Chapel, Copley’s earlier patrons in Portsmouth. Although barely twenty when he painted young Atkinson, Copley demonstrated immense skills in drawing and color, and astutely mined mezzotint portraits of English aristocrats for aspects of pose, setting, and costume.See Trevor Fairbrother, “John Singleton Copley’s Use of British Mezzotints for His American Portraits: A Reappraisal Prompted by New Discoveries,” Arts 55 (Mar. 1981), pp. 122–30. He had learned the techniques of painting by studying the works of other artists who practiced in Boston, including its leading portraitist, John Smibert, but his most dramatic advances took place around 1755 with the arrival in Boston of the English painter Blackburn. By 1758 he had perfected the most distinctive aspects of Blackburn’s manner, including the depiction of fine clothing and mastery of narrative-enhancing poses. Applying these skills to Atkinson’s portrait, he seamlessly incorporated the scion’s aristocratic appearance into the fiction of a young English lord striding forward to survey his country estate. Atkinson’s slender figure virtually inhabited the aggrandizing <em>contrapposto</em> stance with the grace of a dancer. His costume was likely virtual as well, as “invented dress” based on a variety of continental prototypes was common for both male and female portraits in the eighteenth century.Copley’s depiction of both male and female costume is discussed in Aileen Ribeiro‘s “‘The Whole Art of Dress’: Costume in the Work of John Singleton Copley,” in Rebora and Staiti, et al., pp. 103–15. Copley chose to dress Atkinson in a muted salmon coat with deep boot cuffs and matching tight breeches, lavishing attention on his padded silk waistcoat. In a device lifted from contemporary British portraiture, Copley tucked Atkinson’s left hand into his trouser pocket, effectively emphasizing the vest’s silver embroidery and flaunting both its considerable expense and his own genius at rendering sumptuous textiles. Absent from this staging are the classical ruins or attributes of learning so often present in Grand Tour portraits of young British aristocrats. Atkinson’s landscape is pristine and has yet to be imbued with his accomplishments. Instead, evident and intertwined in the Copley portrait of Atkinson are the rising careers of two promising young American men. The combined effects of likeness, costume, and verdant acreage were enough to signal Atkinson’s distinguished pedigree and brilliant future. At the same time, they trumpeted Copley’s own precocious arrival, and his ability to convey personality and social status with skills that surpassed those of any other painter in the colonies, including the much-admired Joseph Blackburn, who unintentionally in the twentieth century wore the laurels of his youthful follower’s acclaim. <strong>Maureen C. O’Brien</strong> <strong>Curator of Painting and Sculpture</strong> ', 'en') (Line: 118) Drupal\filter\Element\ProcessedText::preRenderText(Array) call_user_func_array(Array, Array) (Line: 111) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doTrustedCallback(Array, Array, 'Render #pre_render callbacks must be methods of a class that implements \Drupal\Core\Security\TrustedCallbackInterface or be an anonymous function. The callback was %s. See https://www.drupal.org/node/2966725', 'exception', 'Drupal\Core\Render\Element\RenderCallbackInterface') (Line: 797) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doCallback('#pre_render', Array, Array) (Line: 386) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 106) __TwigTemplate_4039b6d648e4a30fc59604b38849a688->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 46) __TwigTemplate_d1494d795b4bd5366283e85f3e7729dc->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 43) __TwigTemplate_253b62141ad73ee07345b0067cf59829->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/contrib/classy/templates/field/field--text-with-summary.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('field', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 231) __TwigTemplate_d0a4e06ec4cdc862487a9e59e7ee55e6->block_node_content(Array, Array) (Line: 171) Twig\Template->displayBlock('node_content', Array, Array) (Line: 91) __TwigTemplate_fb45c12c057c90d6dad87acc3f8af627->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 51) __TwigTemplate_d0a4e06ec4cdc862487a9e59e7ee55e6->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/content/node--teaser.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('node', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 60) __TwigTemplate_b5820ae2fc9ac809d8bb920432eaa798->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/contrib/classy/templates/views/views-view-unformatted.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('views_view_unformatted', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 129) __TwigTemplate_c1babb60e112ad993125dc5af5a5b779->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/views/views-view--site-search--page-1.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('views_view__site_search__page_1', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array, ) (Line: 238) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\{closure}() (Line: 592) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->executeInRenderContext(Object, Object) (Line: 239) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->prepare(Array, Object, Object) (Line: 128) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->renderResponse(Array, Object, Object) (Line: 90) Drupal\Core\EventSubscriber\MainContentViewSubscriber->onViewRenderArray(Object, 'kernel.view', Object) call_user_func(Array, Object, 'kernel.view', Object) (Line: 111) Drupal\Component\EventDispatcher\ContainerAwareEventDispatcher->dispatch(Object, 'kernel.view') (Line: 186) Symfony\Component\HttpKernel\HttpKernel->handleRaw(Object, 1) (Line: 76) Symfony\Component\HttpKernel\HttpKernel->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 58) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\Session->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 48) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\KernelPreHandle->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 191) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->fetch(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 128) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->lookup(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 82) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 270) Drupal\shield\ShieldMiddleware->bypass(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 137) Drupal\shield\ShieldMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 48) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\ReverseProxyMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 51) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\NegotiationMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 51) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\StackedHttpKernel->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 704) Drupal\Core\DrupalKernel->handle(Object) (Line: 19) - Warning: Undefined array key 0 in Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances() (line 388 of modules/contrib/footnotes/src/Plugin/Filter/FootnotesFilter.php).

Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances('In the January 1920 <em>Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design,</em> RISD Museum director L. Earle Rowe drew attention to the recent acquisition of a colonial American portrait by the British-trained painter L. Earle Rowe, “Portrait of Theodore Atkinson, Jr. by Joseph Blackburn.” Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design, January 1920, VIII, 2–4. Ill. p. 1.. The elegant likeness of young Theodore Atkinson, Jr. (fig. 1), was sold to the museum by a descendant of Atkinson’s mother, Hannah, who with her husband, Theodore Sr., was painted by Blackburn in 1760 (figs. 2 and 3). The parents’ selection of the eminent Blackburn suited their station in life: Hannah was the sister of Benning Wentworth, governor of the province of New Hampshire from 1741 until 1767. Theodore Atkinson, Sr., served as president of the Council of New Hampshire, secretary and chief justice of the colony, and delegate to the Albany Congress. In the 1750s, Blackburn had brought English Rococo style to the sober tradition of American portraiture, and his emphasis on depicting luxurious textiles reinforced his popularity with patrons in Bermuda, Newport, Boston, and Portland, New Hampshire, where the Atkinson family flourished. In contrast to their refined and sober depictions, their son’s livelier image seemed to celebrate the energy and promise of the next generation. Vibrantly colored and meticulously drawn, it represented the twenty-one-year-old Harvard College graduate as if poised to assume his place in the world. The portrait became known as one of Blackburn’s most distinguished works and in 1911 was among a select group of paintings chosen to represent the artist in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Catalogue of an Exhibition of Colonial Portraits: November 6 To December 31, 1911 (1911), no. 2, Theodore Atkinson, Jr., by Joseph B. Blackburn. In 1762, young Atkinson married his pretty young cousin, Frances Deering Wentworth, and subsequently commissioned John Singleton Copley to paint her portrait (Fig. 4). The newlyweds settled in Portsmouth, where Atkinson drew income from land grants and followed a preordained career path in which he served as secretary of the province of New Hampshire, member of His Majesty’s council, and collector of customs. His youthful momentum was tragically cut short in 1769 when he died of consumption at the age of thirty-two. After a notoriously short period of mourning, Frances married John Wentworth, a cousin with strong Tory sympathies, and fled with him to England before the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. By the early twentieth century, the four Atkinson portraits had been separated from one another. Around 1918–1919, the portraits of the colonel and his wife found homes in museums in Worcester, Massachusetts, and Cleveland, Ohio, and Theodore Jr.’s came to Rhode Island. The image of Frances Deering Atkinson had left the fold earlier, and in 1876 entered the New York Public Library by way of the James Lenox collection. (Sold by the library in 2005, her portrait now resides at the Crystal Bridges Museum in Bentonville, Arkansas.) When the younger couple’s likenesses were reunited at the 1911 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, no one seemed to have remarked that the strong color and crisp draftsmanship that characterized the wife’s portrait by Copley were also evident in Theodore’s, or noticed their shared distinctive contrast to the muted tones and simplified construction of the other Blackburn portraits nearby. In New York, the <em>Portrait of Theodore Atkinson, Jr.,</em> continued to signal the older artist’s best and most accomplished work, a position that was reinforced when it was featured as the frontispiece of Lawrence Park’s 1923 monograph <em>Joseph Blackburn: A Colonial Portrait Painter</em>. Art historians are trained to determine the authenticity of works of art by studying their style, construction, and physical appearances, and by documenting their living history and chain of ownership. There was no doubt when the portrait of Theodore Atkinson, Jr., was acquired by RISD that it had descended in an unbroken family succession along with Blackburn’s signed portraits of his parents. Reputable scholars had published it as Blackburn’s work, and although there was no evidence of a signature, this was not uncommon in colonial portraiture. And yet, Earle Rowe was careful to note that the unknowns associated with relatively recent colonial art history were not unlike the challenges faced by Renaissance scholars. He mentioned a lack of documentary evidence about the “shadowy personalities and period of activity” of American artists, admitting that at present “the greatest mystery and fascination surrounds Blackburn, whose work had such a great influence on Copley,” and whose paintings had frequently been ascribed to the younger artist. In this case, Rowe had good reason to be cautious, as the long existence of the younger Atkinson portrait among the Blackburn portraits may have led to attribution by association. Theodore Jr.’s premature death, his wife’s remarriage, and the earlier dispersion of her portrait may have obscured obvious clues to the artist’s identity, for in fact, the 1757–1758 commission for his portrait was executed by Blackburn’s brilliant young follower from Boston: the twenty-year-old John Singleton Copley. The confusion over authorship endured until 1943, when in conjunction with the exhibition <em>New England Painting, 1700</em>–<em>1775</em>, held at the Worcester Art Museum, the American art historian and dealer William Sawitzky argued that the “sculptural form, solidity, linear precision and marmoreal flesh tones are closer to Copley than to Blackburn’s weaker formal sense and greater reliance on chromatic and tonal quality, even allowing for the influence that the precocious Copley exercised on his older English-trained colleague.”“News and Comments,” Magazine of Art 36 (Mar. 1943), p. 115. According to the March 1943 “News and Comments” column of <em>Magazine of Art</em>, Anne Allison, Charles K. Bolton, Louisa Dresser, Henry Wilder Foote, John Hill Morgan, Mrs. Haven Parker, and other experts in attendance agreed, and the portrait was assigned to Copley. Although the circumstances of Copley’s introduction to the Atkinsons are not known, they may have seen his portraits of the Reverend Arthur Browne’s family in Portsmouth, or become aware of the portraits Copley had painted of prominent Bostonians in poses identical to the one later chosen for their son.Janet L. Comey in Carrie Rebora and Paul Staiti, et al., John Singleton Copley in America (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, distributed by Harry N. Abrams, 1995), pp. 178–81, comprehensively analyzed Atkinson’s portrait and identified the similarly posed portraits of Joshua Winslow, 1755 (Santa Barbara Museum of Art) and William Brattle, 1756 (Harvard University Art Museums). She also noted the Atkinsons’ connections to the family of Reverend Arthur Browne of Queen’s Chapel, Copley’s earlier patrons in Portsmouth. Although barely twenty when he painted young Atkinson, Copley demonstrated immense skills in drawing and color, and astutely mined mezzotint portraits of English aristocrats for aspects of pose, setting, and costume.See Trevor Fairbrother, “John Singleton Copley’s Use of British Mezzotints for His American Portraits: A Reappraisal Prompted by New Discoveries,” Arts 55 (Mar. 1981), pp. 122–30. He had learned the techniques of painting by studying the works of other artists who practiced in Boston, including its leading portraitist, John Smibert, but his most dramatic advances took place around 1755 with the arrival in Boston of the English painter Blackburn. By 1758 he had perfected the most distinctive aspects of Blackburn’s manner, including the depiction of fine clothing and mastery of narrative-enhancing poses. Applying these skills to Atkinson’s portrait, he seamlessly incorporated the scion’s aristocratic appearance into the fiction of a young English lord striding forward to survey his country estate. Atkinson’s slender figure virtually inhabited the aggrandizing <em>contrapposto</em> stance with the grace of a dancer. His costume was likely virtual as well, as “invented dress” based on a variety of continental prototypes was common for both male and female portraits in the eighteenth century.Copley’s depiction of both male and female costume is discussed in Aileen Ribeiro‘s “‘The Whole Art of Dress’: Costume in the Work of John Singleton Copley,” in Rebora and Staiti, et al., pp. 103–15. Copley chose to dress Atkinson in a muted salmon coat with deep boot cuffs and matching tight breeches, lavishing attention on his padded silk waistcoat. In a device lifted from contemporary British portraiture, Copley tucked Atkinson’s left hand into his trouser pocket, effectively emphasizing the vest’s silver embroidery and flaunting both its considerable expense and his own genius at rendering sumptuous textiles. Absent from this staging are the classical ruins or attributes of learning so often present in Grand Tour portraits of young British aristocrats. Atkinson’s landscape is pristine and has yet to be imbued with his accomplishments. Instead, evident and intertwined in the Copley portrait of Atkinson are the rising careers of two promising young American men. The combined effects of likeness, costume, and verdant acreage were enough to signal Atkinson’s distinguished pedigree and brilliant future. At the same time, they trumpeted Copley’s own precocious arrival, and his ability to convey personality and social status with skills that surpassed those of any other painter in the colonies, including the much-admired Joseph Blackburn, who unintentionally in the twentieth century wore the laurels of his youthful follower’s acclaim. <strong>Maureen C. O’Brien</strong> <strong>Curator of Painting and Sculpture</strong> ') (Line: 116) Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->process('In the January 1920 <em>Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design,</em> RISD Museum director L. Earle Rowe drew attention to the recent acquisition of a colonial American portrait by the British-trained painter L. Earle Rowe, “Portrait of Theodore Atkinson, Jr. by Joseph Blackburn.” Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design, January 1920, VIII, 2–4. Ill. p. 1.. The elegant likeness of young Theodore Atkinson, Jr. (fig. 1), was sold to the museum by a descendant of Atkinson’s mother, Hannah, who with her husband, Theodore Sr., was painted by Blackburn in 1760 (figs. 2 and 3). The parents’ selection of the eminent Blackburn suited their station in life: Hannah was the sister of Benning Wentworth, governor of the province of New Hampshire from 1741 until 1767. Theodore Atkinson, Sr., served as president of the Council of New Hampshire, secretary and chief justice of the colony, and delegate to the Albany Congress. In the 1750s, Blackburn had brought English Rococo style to the sober tradition of American portraiture, and his emphasis on depicting luxurious textiles reinforced his popularity with patrons in Bermuda, Newport, Boston, and Portland, New Hampshire, where the Atkinson family flourished. In contrast to their refined and sober depictions, their son’s livelier image seemed to celebrate the energy and promise of the next generation. Vibrantly colored and meticulously drawn, it represented the twenty-one-year-old Harvard College graduate as if poised to assume his place in the world. The portrait became known as one of Blackburn’s most distinguished works and in 1911 was among a select group of paintings chosen to represent the artist in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Catalogue of an Exhibition of Colonial Portraits: November 6 To December 31, 1911 (1911), no. 2, Theodore Atkinson, Jr., by Joseph B. Blackburn. In 1762, young Atkinson married his pretty young cousin, Frances Deering Wentworth, and subsequently commissioned John Singleton Copley to paint her portrait (Fig. 4). The newlyweds settled in Portsmouth, where Atkinson drew income from land grants and followed a preordained career path in which he served as secretary of the province of New Hampshire, member of His Majesty’s council, and collector of customs. His youthful momentum was tragically cut short in 1769 when he died of consumption at the age of thirty-two. After a notoriously short period of mourning, Frances married John Wentworth, a cousin with strong Tory sympathies, and fled with him to England before the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. By the early twentieth century, the four Atkinson portraits had been separated from one another. Around 1918–1919, the portraits of the colonel and his wife found homes in museums in Worcester, Massachusetts, and Cleveland, Ohio, and Theodore Jr.’s came to Rhode Island. The image of Frances Deering Atkinson had left the fold earlier, and in 1876 entered the New York Public Library by way of the James Lenox collection. (Sold by the library in 2005, her portrait now resides at the Crystal Bridges Museum in Bentonville, Arkansas.) When the younger couple’s likenesses were reunited at the 1911 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, no one seemed to have remarked that the strong color and crisp draftsmanship that characterized the wife’s portrait by Copley were also evident in Theodore’s, or noticed their shared distinctive contrast to the muted tones and simplified construction of the other Blackburn portraits nearby. In New York, the <em>Portrait of Theodore Atkinson, Jr.,</em> continued to signal the older artist’s best and most accomplished work, a position that was reinforced when it was featured as the frontispiece of Lawrence Park’s 1923 monograph <em>Joseph Blackburn: A Colonial Portrait Painter</em>. Art historians are trained to determine the authenticity of works of art by studying their style, construction, and physical appearances, and by documenting their living history and chain of ownership. There was no doubt when the portrait of Theodore Atkinson, Jr., was acquired by RISD that it had descended in an unbroken family succession along with Blackburn’s signed portraits of his parents. Reputable scholars had published it as Blackburn’s work, and although there was no evidence of a signature, this was not uncommon in colonial portraiture. And yet, Earle Rowe was careful to note that the unknowns associated with relatively recent colonial art history were not unlike the challenges faced by Renaissance scholars. He mentioned a lack of documentary evidence about the “shadowy personalities and period of activity” of American artists, admitting that at present “the greatest mystery and fascination surrounds Blackburn, whose work had such a great influence on Copley,” and whose paintings had frequently been ascribed to the younger artist. In this case, Rowe had good reason to be cautious, as the long existence of the younger Atkinson portrait among the Blackburn portraits may have led to attribution by association. Theodore Jr.’s premature death, his wife’s remarriage, and the earlier dispersion of her portrait may have obscured obvious clues to the artist’s identity, for in fact, the 1757–1758 commission for his portrait was executed by Blackburn’s brilliant young follower from Boston: the twenty-year-old John Singleton Copley. The confusion over authorship endured until 1943, when in conjunction with the exhibition <em>New England Painting, 1700</em>–<em>1775</em>, held at the Worcester Art Museum, the American art historian and dealer William Sawitzky argued that the “sculptural form, solidity, linear precision and marmoreal flesh tones are closer to Copley than to Blackburn’s weaker formal sense and greater reliance on chromatic and tonal quality, even allowing for the influence that the precocious Copley exercised on his older English-trained colleague.”“News and Comments,” Magazine of Art 36 (Mar. 1943), p. 115. According to the March 1943 “News and Comments” column of <em>Magazine of Art</em>, Anne Allison, Charles K. Bolton, Louisa Dresser, Henry Wilder Foote, John Hill Morgan, Mrs. Haven Parker, and other experts in attendance agreed, and the portrait was assigned to Copley. Although the circumstances of Copley’s introduction to the Atkinsons are not known, they may have seen his portraits of the Reverend Arthur Browne’s family in Portsmouth, or become aware of the portraits Copley had painted of prominent Bostonians in poses identical to the one later chosen for their son.Janet L. Comey in Carrie Rebora and Paul Staiti, et al., John Singleton Copley in America (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, distributed by Harry N. Abrams, 1995), pp. 178–81, comprehensively analyzed Atkinson’s portrait and identified the similarly posed portraits of Joshua Winslow, 1755 (Santa Barbara Museum of Art) and William Brattle, 1756 (Harvard University Art Museums). She also noted the Atkinsons’ connections to the family of Reverend Arthur Browne of Queen’s Chapel, Copley’s earlier patrons in Portsmouth. Although barely twenty when he painted young Atkinson, Copley demonstrated immense skills in drawing and color, and astutely mined mezzotint portraits of English aristocrats for aspects of pose, setting, and costume.See Trevor Fairbrother, “John Singleton Copley’s Use of British Mezzotints for His American Portraits: A Reappraisal Prompted by New Discoveries,” Arts 55 (Mar. 1981), pp. 122–30. He had learned the techniques of painting by studying the works of other artists who practiced in Boston, including its leading portraitist, John Smibert, but his most dramatic advances took place around 1755 with the arrival in Boston of the English painter Blackburn. By 1758 he had perfected the most distinctive aspects of Blackburn’s manner, including the depiction of fine clothing and mastery of narrative-enhancing poses. Applying these skills to Atkinson’s portrait, he seamlessly incorporated the scion’s aristocratic appearance into the fiction of a young English lord striding forward to survey his country estate. Atkinson’s slender figure virtually inhabited the aggrandizing <em>contrapposto</em> stance with the grace of a dancer. His costume was likely virtual as well, as “invented dress” based on a variety of continental prototypes was common for both male and female portraits in the eighteenth century.Copley’s depiction of both male and female costume is discussed in Aileen Ribeiro‘s “‘The Whole Art of Dress’: Costume in the Work of John Singleton Copley,” in Rebora and Staiti, et al., pp. 103–15. Copley chose to dress Atkinson in a muted salmon coat with deep boot cuffs and matching tight breeches, lavishing attention on his padded silk waistcoat. In a device lifted from contemporary British portraiture, Copley tucked Atkinson’s left hand into his trouser pocket, effectively emphasizing the vest’s silver embroidery and flaunting both its considerable expense and his own genius at rendering sumptuous textiles. Absent from this staging are the classical ruins or attributes of learning so often present in Grand Tour portraits of young British aristocrats. Atkinson’s landscape is pristine and has yet to be imbued with his accomplishments. Instead, evident and intertwined in the Copley portrait of Atkinson are the rising careers of two promising young American men. The combined effects of likeness, costume, and verdant acreage were enough to signal Atkinson’s distinguished pedigree and brilliant future. At the same time, they trumpeted Copley’s own precocious arrival, and his ability to convey personality and social status with skills that surpassed those of any other painter in the colonies, including the much-admired Joseph Blackburn, who unintentionally in the twentieth century wore the laurels of his youthful follower’s acclaim. <strong>Maureen C. O’Brien</strong> <strong>Curator of Painting and Sculpture</strong> ', 'en') (Line: 118) Drupal\filter\Element\ProcessedText::preRenderText(Array) call_user_func_array(Array, Array) (Line: 111) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doTrustedCallback(Array, Array, 'Render #pre_render callbacks must be methods of a class that implements \Drupal\Core\Security\TrustedCallbackInterface or be an anonymous function. The callback was %s. See https://www.drupal.org/node/2966725', 'exception', 'Drupal\Core\Render\Element\RenderCallbackInterface') (Line: 797) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doCallback('#pre_render', Array, Array) (Line: 386) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 106) __TwigTemplate_4039b6d648e4a30fc59604b38849a688->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 46) __TwigTemplate_d1494d795b4bd5366283e85f3e7729dc->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 43) __TwigTemplate_253b62141ad73ee07345b0067cf59829->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/contrib/classy/templates/field/field--text-with-summary.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('field', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 231) __TwigTemplate_d0a4e06ec4cdc862487a9e59e7ee55e6->block_node_content(Array, Array) (Line: 171) Twig\Template->displayBlock('node_content', Array, Array) (Line: 91) __TwigTemplate_fb45c12c057c90d6dad87acc3f8af627->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 51) __TwigTemplate_d0a4e06ec4cdc862487a9e59e7ee55e6->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/content/node--teaser.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('node', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 60) __TwigTemplate_b5820ae2fc9ac809d8bb920432eaa798->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/contrib/classy/templates/views/views-view-unformatted.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('views_view_unformatted', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 129) __TwigTemplate_c1babb60e112ad993125dc5af5a5b779->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/views/views-view--site-search--page-1.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('views_view__site_search__page_1', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array, ) (Line: 238) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\{closure}() (Line: 592) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->executeInRenderContext(Object, Object) (Line: 239) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->prepare(Array, Object, Object) (Line: 128) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->renderResponse(Array, Object, Object) (Line: 90) Drupal\Core\EventSubscriber\MainContentViewSubscriber->onViewRenderArray(Object, 'kernel.view', Object) call_user_func(Array, Object, 'kernel.view', Object) (Line: 111) Drupal\Component\EventDispatcher\ContainerAwareEventDispatcher->dispatch(Object, 'kernel.view') (Line: 186) Symfony\Component\HttpKernel\HttpKernel->handleRaw(Object, 1) (Line: 76) Symfony\Component\HttpKernel\HttpKernel->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 58) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\Session->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 48) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\KernelPreHandle->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 191) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->fetch(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 128) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->lookup(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 82) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 270) Drupal\shield\ShieldMiddleware->bypass(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 137) Drupal\shield\ShieldMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 48) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\ReverseProxyMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 51) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\NegotiationMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 51) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\StackedHttpKernel->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 704) Drupal\Core\DrupalKernel->handle(Object) (Line: 19) - Warning: Undefined array key 0 in Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances() (line 392 of modules/contrib/footnotes/src/Plugin/Filter/FootnotesFilter.php).