Error message

- Warning: Undefined array key 0 in Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances() (line 388 of modules/contrib/footnotes/src/Plugin/Filter/FootnotesFilter.php).

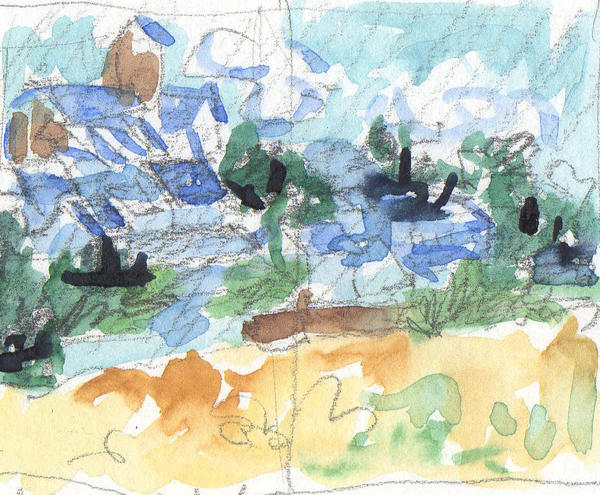

Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances('Albert Bierstadt was born in Solingen, Germany, but came to the United States with his family in 1832 and settled with them in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Although details of his early artistic training are unknown, by 1850 he advertised himself as a teacher of “an improved system of monochromatic painting.”Nancy K. Anderson and Linda S. Ferber, in Albert Bierstadt: Art and Enterprise (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with the Brooklyn Museum, 1990), 115; their Chronology section notes the first advertisement of Bierstadt’s services in the New Bedford Standard of May 13, 1850, and cites Richard Schafer Trump, The Life and Works of Albert Bierstadt (dissertation, Ohio State University, 1963), 23, for quoting a broadside of June 6, 1850, promoting his “improved system.” The following year he added instruction in “Painting Colored Crayon Heads and Landscapes from nature, or from copies,” as well as “a new style of sketching from nature which can be acquired in one lesson.”Newport Daily News, June 7, 1851, cited in Anderson and Ferber 1990, 116. During the early 1850s, Bierstadt exhibited his work in Boston and collaborated with the American artist George Harvey on a light show that utilized the latter’s “dissolving views” of landscapes painted on glass.Anderson and Ferber, 116. In 1853 Bierstadt became a naturalized American citizen and returned to Germany to continue his own artistic education. When Bierstadt arrived in Europe he was disappointed to learn of the death of Johann Peter Hasenclever, the noted Düsseldorf genre painter with whom he had planned to study. He remained in that city, however, and although he did not officially enter the Düsseldorf Academy, he progressed quickly under the guidance of American colleagues Worthington Whittredge and Emanuel Leutze, the German landscape painter Andreas Achenbach, and the circle of artists around Carl Friedrich Lessing. The hallmarks of Düsseldorf painting at mid-century were accurate draftsmanship and truthful rendering of natural forms, applied equally to figures and to landscape. In the process of mastering this style, Bierstadt set out in the spring of 1854 to explore the Westphalian countryside and to make careful sketches that could become the sources for paintings. In <em>Landscape on the Rhine</em>, one of the drawings from that first sketching trip, Bierstadt described the yard of a cooperage on the banks of the Rhine. Using only pencil and opaque white wash, he coaxed a landscape from the uniform tan tone of a smooth-surfaced paper. The subject might have attracted Bierstadt for personal reasons: his father had emigrated from Germany as a cooper and continued to practice this trade in the United States. Set in a shallow cove, the scene provides a glimpse of local industry that adds distinctive genre elements to the landscape. While there are no descriptive signs of the workshop or forge, whole barrels are visible at left, and others with sprung rims, broken staves, and missing heads are scattered about the foreground. Bierstadt made numerous costume studies as part of his Düsseldorf training and used this knowledge to distinguish the figures in his compositions. Of the four men depicted here, the two wearing wide-brimmed black hats may have come from a nearby vineyard or granary to negotiate the purchase or repair of the barrels. The old stone structure, which could have served as the cooper’s shop, supplies the drawing with a picturesque focus and randomly separates sunlight from shadow through the boards of its wooden awning. Its humble profile stands in contrast to the sweeping cliffs that prefigure the dramatic settings of Bierstadt’s later work. Ruins, old mills, and barns were familiar motifs in landscape paintings. Fallen into decay, they suggested reunion with nature; when still in use, they depicted aspects of times past, or of rural commerce, which appealed to urban collectors. The drawing is carefully organized on the sheet—which is signed with Bierstadt’s monogram on a barrel at left, and dated—and projects a sense of completion. It may have been exchanged with a colleague or given to a friend or family member as a gift, although the primary purpose of drawings made on sketching trips was to serve as sources in the preparation of larger works. The abrupt definition of the cliffs along the shoreline, the effective elimination of middle distance, and the sketchy rendering of trees and grasses reinforce the fact that Bierstadt’s interest was directed to the foreground motif. Although not identified with a documented work, the vignette of the cooperage might have been included in one of the paintings of the following year that incorporated both genre elements and rustic architecture in broader landscape settings.Among the Düsseldorf subjects that included related architectural elements were Westphalian Landscape (1855, Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vermont), A Rustic Mill (1855, private collection; illustrated in Anderson and Ferber 1990, 125), and The Old Mill (1855, private collection; illustrated in Anderson and Ferber 1990, 128). Bierstadt’s method of accumulating numerous detailed sketches remained his modus operandi when he explored the American West. The precision of his Western views was also facilitated by photography, the profession adopted by his brothers Charles and Edward. With the destruction of Bierstadt’s Hudson River home and studio by fire in 1882, many of the drawings that he had made throughout his career were lost. Of those that remained in private hands, <em>Landscape on the Rhine</em> is a revealing document of his Düsseldorf training and his early skill as a draftsman. Landscape and Leisure: 19th-Century American Drawings from the Collection is on view at the RISD Museum from March 13 – July 19, 2015. Maureen O’Brien Curator of Painting and Sculpture ') (Line: 116) Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->process('Albert Bierstadt was born in Solingen, Germany, but came to the United States with his family in 1832 and settled with them in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Although details of his early artistic training are unknown, by 1850 he advertised himself as a teacher of “an improved system of monochromatic painting.”Nancy K. Anderson and Linda S. Ferber, in Albert Bierstadt: Art and Enterprise (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with the Brooklyn Museum, 1990), 115; their Chronology section notes the first advertisement of Bierstadt’s services in the New Bedford Standard of May 13, 1850, and cites Richard Schafer Trump, The Life and Works of Albert Bierstadt (dissertation, Ohio State University, 1963), 23, for quoting a broadside of June 6, 1850, promoting his “improved system.” The following year he added instruction in “Painting Colored Crayon Heads and Landscapes from nature, or from copies,” as well as “a new style of sketching from nature which can be acquired in one lesson.”Newport Daily News, June 7, 1851, cited in Anderson and Ferber 1990, 116. During the early 1850s, Bierstadt exhibited his work in Boston and collaborated with the American artist George Harvey on a light show that utilized the latter’s “dissolving views” of landscapes painted on glass.Anderson and Ferber, 116. In 1853 Bierstadt became a naturalized American citizen and returned to Germany to continue his own artistic education. When Bierstadt arrived in Europe he was disappointed to learn of the death of Johann Peter Hasenclever, the noted Düsseldorf genre painter with whom he had planned to study. He remained in that city, however, and although he did not officially enter the Düsseldorf Academy, he progressed quickly under the guidance of American colleagues Worthington Whittredge and Emanuel Leutze, the German landscape painter Andreas Achenbach, and the circle of artists around Carl Friedrich Lessing. The hallmarks of Düsseldorf painting at mid-century were accurate draftsmanship and truthful rendering of natural forms, applied equally to figures and to landscape. In the process of mastering this style, Bierstadt set out in the spring of 1854 to explore the Westphalian countryside and to make careful sketches that could become the sources for paintings. In <em>Landscape on the Rhine</em>, one of the drawings from that first sketching trip, Bierstadt described the yard of a cooperage on the banks of the Rhine. Using only pencil and opaque white wash, he coaxed a landscape from the uniform tan tone of a smooth-surfaced paper. The subject might have attracted Bierstadt for personal reasons: his father had emigrated from Germany as a cooper and continued to practice this trade in the United States. Set in a shallow cove, the scene provides a glimpse of local industry that adds distinctive genre elements to the landscape. While there are no descriptive signs of the workshop or forge, whole barrels are visible at left, and others with sprung rims, broken staves, and missing heads are scattered about the foreground. Bierstadt made numerous costume studies as part of his Düsseldorf training and used this knowledge to distinguish the figures in his compositions. Of the four men depicted here, the two wearing wide-brimmed black hats may have come from a nearby vineyard or granary to negotiate the purchase or repair of the barrels. The old stone structure, which could have served as the cooper’s shop, supplies the drawing with a picturesque focus and randomly separates sunlight from shadow through the boards of its wooden awning. Its humble profile stands in contrast to the sweeping cliffs that prefigure the dramatic settings of Bierstadt’s later work. Ruins, old mills, and barns were familiar motifs in landscape paintings. Fallen into decay, they suggested reunion with nature; when still in use, they depicted aspects of times past, or of rural commerce, which appealed to urban collectors. The drawing is carefully organized on the sheet—which is signed with Bierstadt’s monogram on a barrel at left, and dated—and projects a sense of completion. It may have been exchanged with a colleague or given to a friend or family member as a gift, although the primary purpose of drawings made on sketching trips was to serve as sources in the preparation of larger works. The abrupt definition of the cliffs along the shoreline, the effective elimination of middle distance, and the sketchy rendering of trees and grasses reinforce the fact that Bierstadt’s interest was directed to the foreground motif. Although not identified with a documented work, the vignette of the cooperage might have been included in one of the paintings of the following year that incorporated both genre elements and rustic architecture in broader landscape settings.Among the Düsseldorf subjects that included related architectural elements were Westphalian Landscape (1855, Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vermont), A Rustic Mill (1855, private collection; illustrated in Anderson and Ferber 1990, 125), and The Old Mill (1855, private collection; illustrated in Anderson and Ferber 1990, 128). Bierstadt’s method of accumulating numerous detailed sketches remained his modus operandi when he explored the American West. The precision of his Western views was also facilitated by photography, the profession adopted by his brothers Charles and Edward. With the destruction of Bierstadt’s Hudson River home and studio by fire in 1882, many of the drawings that he had made throughout his career were lost. Of those that remained in private hands, <em>Landscape on the Rhine</em> is a revealing document of his Düsseldorf training and his early skill as a draftsman. Landscape and Leisure: 19th-Century American Drawings from the Collection is on view at the RISD Museum from March 13 – July 19, 2015. Maureen O’Brien Curator of Painting and Sculpture ', 'en') (Line: 118) Drupal\filter\Element\ProcessedText::preRenderText(Array) call_user_func_array(Array, Array) (Line: 111) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doTrustedCallback(Array, Array, 'Render #pre_render callbacks must be methods of a class that implements \Drupal\Core\Security\TrustedCallbackInterface or be an anonymous function. The callback was %s. See https://www.drupal.org/node/2966725', 'exception', 'Drupal\Core\Render\Element\RenderCallbackInterface') (Line: 797) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doCallback('#pre_render', Array, Array) (Line: 386) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 106) __TwigTemplate_4039b6d648e4a30fc59604b38849a688->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 46) __TwigTemplate_d1494d795b4bd5366283e85f3e7729dc->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 43) __TwigTemplate_253b62141ad73ee07345b0067cf59829->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/contrib/classy/templates/field/field--text-with-summary.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('field', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 231) __TwigTemplate_d0a4e06ec4cdc862487a9e59e7ee55e6->block_node_content(Array, Array) (Line: 171) Twig\Template->displayBlock('node_content', Array, Array) (Line: 91) __TwigTemplate_fb45c12c057c90d6dad87acc3f8af627->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 51) __TwigTemplate_d0a4e06ec4cdc862487a9e59e7ee55e6->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/content/node--teaser.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('node', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 60) __TwigTemplate_b5820ae2fc9ac809d8bb920432eaa798->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/contrib/classy/templates/views/views-view-unformatted.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('views_view_unformatted', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 129) __TwigTemplate_c1babb60e112ad993125dc5af5a5b779->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/views/views-view--site-search--page-1.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('views_view__site_search__page_1', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array, ) (Line: 238) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\{closure}() (Line: 592) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->executeInRenderContext(Object, Object) (Line: 239) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->prepare(Array, Object, Object) (Line: 128) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->renderResponse(Array, Object, Object) (Line: 90) Drupal\Core\EventSubscriber\MainContentViewSubscriber->onViewRenderArray(Object, 'kernel.view', Object) call_user_func(Array, Object, 'kernel.view', Object) (Line: 111) Drupal\Component\EventDispatcher\ContainerAwareEventDispatcher->dispatch(Object, 'kernel.view') (Line: 186) Symfony\Component\HttpKernel\HttpKernel->handleRaw(Object, 1) (Line: 76) Symfony\Component\HttpKernel\HttpKernel->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 58) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\Session->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 48) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\KernelPreHandle->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 191) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->fetch(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 128) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->lookup(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 82) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 270) Drupal\shield\ShieldMiddleware->bypass(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 137) Drupal\shield\ShieldMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 48) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\ReverseProxyMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 51) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\NegotiationMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 51) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\StackedHttpKernel->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 704) Drupal\Core\DrupalKernel->handle(Object) (Line: 19) - Warning: Undefined array key 0 in Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances() (line 389 of modules/contrib/footnotes/src/Plugin/Filter/FootnotesFilter.php).

Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances('Albert Bierstadt was born in Solingen, Germany, but came to the United States with his family in 1832 and settled with them in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Although details of his early artistic training are unknown, by 1850 he advertised himself as a teacher of “an improved system of monochromatic painting.”Nancy K. Anderson and Linda S. Ferber, in Albert Bierstadt: Art and Enterprise (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with the Brooklyn Museum, 1990), 115; their Chronology section notes the first advertisement of Bierstadt’s services in the New Bedford Standard of May 13, 1850, and cites Richard Schafer Trump, The Life and Works of Albert Bierstadt (dissertation, Ohio State University, 1963), 23, for quoting a broadside of June 6, 1850, promoting his “improved system.” The following year he added instruction in “Painting Colored Crayon Heads and Landscapes from nature, or from copies,” as well as “a new style of sketching from nature which can be acquired in one lesson.”Newport Daily News, June 7, 1851, cited in Anderson and Ferber 1990, 116. During the early 1850s, Bierstadt exhibited his work in Boston and collaborated with the American artist George Harvey on a light show that utilized the latter’s “dissolving views” of landscapes painted on glass.Anderson and Ferber, 116. In 1853 Bierstadt became a naturalized American citizen and returned to Germany to continue his own artistic education. When Bierstadt arrived in Europe he was disappointed to learn of the death of Johann Peter Hasenclever, the noted Düsseldorf genre painter with whom he had planned to study. He remained in that city, however, and although he did not officially enter the Düsseldorf Academy, he progressed quickly under the guidance of American colleagues Worthington Whittredge and Emanuel Leutze, the German landscape painter Andreas Achenbach, and the circle of artists around Carl Friedrich Lessing. The hallmarks of Düsseldorf painting at mid-century were accurate draftsmanship and truthful rendering of natural forms, applied equally to figures and to landscape. In the process of mastering this style, Bierstadt set out in the spring of 1854 to explore the Westphalian countryside and to make careful sketches that could become the sources for paintings. In <em>Landscape on the Rhine</em>, one of the drawings from that first sketching trip, Bierstadt described the yard of a cooperage on the banks of the Rhine. Using only pencil and opaque white wash, he coaxed a landscape from the uniform tan tone of a smooth-surfaced paper. The subject might have attracted Bierstadt for personal reasons: his father had emigrated from Germany as a cooper and continued to practice this trade in the United States. Set in a shallow cove, the scene provides a glimpse of local industry that adds distinctive genre elements to the landscape. While there are no descriptive signs of the workshop or forge, whole barrels are visible at left, and others with sprung rims, broken staves, and missing heads are scattered about the foreground. Bierstadt made numerous costume studies as part of his Düsseldorf training and used this knowledge to distinguish the figures in his compositions. Of the four men depicted here, the two wearing wide-brimmed black hats may have come from a nearby vineyard or granary to negotiate the purchase or repair of the barrels. The old stone structure, which could have served as the cooper’s shop, supplies the drawing with a picturesque focus and randomly separates sunlight from shadow through the boards of its wooden awning. Its humble profile stands in contrast to the sweeping cliffs that prefigure the dramatic settings of Bierstadt’s later work. Ruins, old mills, and barns were familiar motifs in landscape paintings. Fallen into decay, they suggested reunion with nature; when still in use, they depicted aspects of times past, or of rural commerce, which appealed to urban collectors. The drawing is carefully organized on the sheet—which is signed with Bierstadt’s monogram on a barrel at left, and dated—and projects a sense of completion. It may have been exchanged with a colleague or given to a friend or family member as a gift, although the primary purpose of drawings made on sketching trips was to serve as sources in the preparation of larger works. The abrupt definition of the cliffs along the shoreline, the effective elimination of middle distance, and the sketchy rendering of trees and grasses reinforce the fact that Bierstadt’s interest was directed to the foreground motif. Although not identified with a documented work, the vignette of the cooperage might have been included in one of the paintings of the following year that incorporated both genre elements and rustic architecture in broader landscape settings.Among the Düsseldorf subjects that included related architectural elements were Westphalian Landscape (1855, Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vermont), A Rustic Mill (1855, private collection; illustrated in Anderson and Ferber 1990, 125), and The Old Mill (1855, private collection; illustrated in Anderson and Ferber 1990, 128). Bierstadt’s method of accumulating numerous detailed sketches remained his modus operandi when he explored the American West. The precision of his Western views was also facilitated by photography, the profession adopted by his brothers Charles and Edward. With the destruction of Bierstadt’s Hudson River home and studio by fire in 1882, many of the drawings that he had made throughout his career were lost. Of those that remained in private hands, <em>Landscape on the Rhine</em> is a revealing document of his Düsseldorf training and his early skill as a draftsman. Landscape and Leisure: 19th-Century American Drawings from the Collection is on view at the RISD Museum from March 13 – July 19, 2015. Maureen O’Brien Curator of Painting and Sculpture ') (Line: 116) Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->process('Albert Bierstadt was born in Solingen, Germany, but came to the United States with his family in 1832 and settled with them in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Although details of his early artistic training are unknown, by 1850 he advertised himself as a teacher of “an improved system of monochromatic painting.”Nancy K. Anderson and Linda S. Ferber, in Albert Bierstadt: Art and Enterprise (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with the Brooklyn Museum, 1990), 115; their Chronology section notes the first advertisement of Bierstadt’s services in the New Bedford Standard of May 13, 1850, and cites Richard Schafer Trump, The Life and Works of Albert Bierstadt (dissertation, Ohio State University, 1963), 23, for quoting a broadside of June 6, 1850, promoting his “improved system.” The following year he added instruction in “Painting Colored Crayon Heads and Landscapes from nature, or from copies,” as well as “a new style of sketching from nature which can be acquired in one lesson.”Newport Daily News, June 7, 1851, cited in Anderson and Ferber 1990, 116. During the early 1850s, Bierstadt exhibited his work in Boston and collaborated with the American artist George Harvey on a light show that utilized the latter’s “dissolving views” of landscapes painted on glass.Anderson and Ferber, 116. In 1853 Bierstadt became a naturalized American citizen and returned to Germany to continue his own artistic education. When Bierstadt arrived in Europe he was disappointed to learn of the death of Johann Peter Hasenclever, the noted Düsseldorf genre painter with whom he had planned to study. He remained in that city, however, and although he did not officially enter the Düsseldorf Academy, he progressed quickly under the guidance of American colleagues Worthington Whittredge and Emanuel Leutze, the German landscape painter Andreas Achenbach, and the circle of artists around Carl Friedrich Lessing. The hallmarks of Düsseldorf painting at mid-century were accurate draftsmanship and truthful rendering of natural forms, applied equally to figures and to landscape. In the process of mastering this style, Bierstadt set out in the spring of 1854 to explore the Westphalian countryside and to make careful sketches that could become the sources for paintings. In <em>Landscape on the Rhine</em>, one of the drawings from that first sketching trip, Bierstadt described the yard of a cooperage on the banks of the Rhine. Using only pencil and opaque white wash, he coaxed a landscape from the uniform tan tone of a smooth-surfaced paper. The subject might have attracted Bierstadt for personal reasons: his father had emigrated from Germany as a cooper and continued to practice this trade in the United States. Set in a shallow cove, the scene provides a glimpse of local industry that adds distinctive genre elements to the landscape. While there are no descriptive signs of the workshop or forge, whole barrels are visible at left, and others with sprung rims, broken staves, and missing heads are scattered about the foreground. Bierstadt made numerous costume studies as part of his Düsseldorf training and used this knowledge to distinguish the figures in his compositions. Of the four men depicted here, the two wearing wide-brimmed black hats may have come from a nearby vineyard or granary to negotiate the purchase or repair of the barrels. The old stone structure, which could have served as the cooper’s shop, supplies the drawing with a picturesque focus and randomly separates sunlight from shadow through the boards of its wooden awning. Its humble profile stands in contrast to the sweeping cliffs that prefigure the dramatic settings of Bierstadt’s later work. Ruins, old mills, and barns were familiar motifs in landscape paintings. Fallen into decay, they suggested reunion with nature; when still in use, they depicted aspects of times past, or of rural commerce, which appealed to urban collectors. The drawing is carefully organized on the sheet—which is signed with Bierstadt’s monogram on a barrel at left, and dated—and projects a sense of completion. It may have been exchanged with a colleague or given to a friend or family member as a gift, although the primary purpose of drawings made on sketching trips was to serve as sources in the preparation of larger works. The abrupt definition of the cliffs along the shoreline, the effective elimination of middle distance, and the sketchy rendering of trees and grasses reinforce the fact that Bierstadt’s interest was directed to the foreground motif. Although not identified with a documented work, the vignette of the cooperage might have been included in one of the paintings of the following year that incorporated both genre elements and rustic architecture in broader landscape settings.Among the Düsseldorf subjects that included related architectural elements were Westphalian Landscape (1855, Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vermont), A Rustic Mill (1855, private collection; illustrated in Anderson and Ferber 1990, 125), and The Old Mill (1855, private collection; illustrated in Anderson and Ferber 1990, 128). Bierstadt’s method of accumulating numerous detailed sketches remained his modus operandi when he explored the American West. The precision of his Western views was also facilitated by photography, the profession adopted by his brothers Charles and Edward. With the destruction of Bierstadt’s Hudson River home and studio by fire in 1882, many of the drawings that he had made throughout his career were lost. Of those that remained in private hands, <em>Landscape on the Rhine</em> is a revealing document of his Düsseldorf training and his early skill as a draftsman. Landscape and Leisure: 19th-Century American Drawings from the Collection is on view at the RISD Museum from March 13 – July 19, 2015. Maureen O’Brien Curator of Painting and Sculpture ', 'en') (Line: 118) Drupal\filter\Element\ProcessedText::preRenderText(Array) call_user_func_array(Array, Array) (Line: 111) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doTrustedCallback(Array, Array, 'Render #pre_render callbacks must be methods of a class that implements \Drupal\Core\Security\TrustedCallbackInterface or be an anonymous function. The callback was %s. See https://www.drupal.org/node/2966725', 'exception', 'Drupal\Core\Render\Element\RenderCallbackInterface') (Line: 797) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doCallback('#pre_render', Array, Array) (Line: 386) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 106) __TwigTemplate_4039b6d648e4a30fc59604b38849a688->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 46) __TwigTemplate_d1494d795b4bd5366283e85f3e7729dc->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 43) __TwigTemplate_253b62141ad73ee07345b0067cf59829->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/contrib/classy/templates/field/field--text-with-summary.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('field', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 231) __TwigTemplate_d0a4e06ec4cdc862487a9e59e7ee55e6->block_node_content(Array, Array) (Line: 171) Twig\Template->displayBlock('node_content', Array, Array) (Line: 91) __TwigTemplate_fb45c12c057c90d6dad87acc3f8af627->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 51) __TwigTemplate_d0a4e06ec4cdc862487a9e59e7ee55e6->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/content/node--teaser.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('node', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 60) __TwigTemplate_b5820ae2fc9ac809d8bb920432eaa798->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/contrib/classy/templates/views/views-view-unformatted.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('views_view_unformatted', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 129) __TwigTemplate_c1babb60e112ad993125dc5af5a5b779->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/views/views-view--site-search--page-1.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('views_view__site_search__page_1', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array, ) (Line: 238) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\{closure}() (Line: 592) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->executeInRenderContext(Object, Object) (Line: 239) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->prepare(Array, Object, Object) (Line: 128) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->renderResponse(Array, Object, Object) (Line: 90) Drupal\Core\EventSubscriber\MainContentViewSubscriber->onViewRenderArray(Object, 'kernel.view', Object) call_user_func(Array, Object, 'kernel.view', Object) (Line: 111) Drupal\Component\EventDispatcher\ContainerAwareEventDispatcher->dispatch(Object, 'kernel.view') (Line: 186) Symfony\Component\HttpKernel\HttpKernel->handleRaw(Object, 1) (Line: 76) Symfony\Component\HttpKernel\HttpKernel->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 58) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\Session->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 48) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\KernelPreHandle->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 191) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->fetch(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 128) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->lookup(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 82) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 270) Drupal\shield\ShieldMiddleware->bypass(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 137) Drupal\shield\ShieldMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 48) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\ReverseProxyMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 51) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\NegotiationMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 51) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\StackedHttpKernel->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 704) Drupal\Core\DrupalKernel->handle(Object) (Line: 19) - Warning: Undefined array key 0 in Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances() (line 388 of modules/contrib/footnotes/src/Plugin/Filter/FootnotesFilter.php).

Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances('Albert Bierstadt was born in Solingen, Germany, but came to the United States with his family in 1832 and settled with them in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Although details of his early artistic training are unknown, by 1850 he advertised himself as a teacher of “an improved system of monochromatic painting.”Nancy K. Anderson and Linda S. Ferber, in Albert Bierstadt: Art and Enterprise (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with the Brooklyn Museum, 1990), 115; their Chronology section notes the first advertisement of Bierstadt’s services in the New Bedford Standard of May 13, 1850, and cites Richard Schafer Trump, The Life and Works of Albert Bierstadt (dissertation, Ohio State University, 1963), 23, for quoting a broadside of June 6, 1850, promoting his “improved system.” The following year he added instruction in “Painting Colored Crayon Heads and Landscapes from nature, or from copies,” as well as “a new style of sketching from nature which can be acquired in one lesson.”Newport Daily News, June 7, 1851, cited in Anderson and Ferber 1990, 116. During the early 1850s, Bierstadt exhibited his work in Boston and collaborated with the American artist George Harvey on a light show that utilized the latter’s “dissolving views” of landscapes painted on glass.Anderson and Ferber, 116. In 1853 Bierstadt became a naturalized American citizen and returned to Germany to continue his own artistic education. When Bierstadt arrived in Europe he was disappointed to learn of the death of Johann Peter Hasenclever, the noted Düsseldorf genre painter with whom he had planned to study. He remained in that city, however, and although he did not officially enter the Düsseldorf Academy, he progressed quickly under the guidance of American colleagues Worthington Whittredge and Emanuel Leutze, the German landscape painter Andreas Achenbach, and the circle of artists around Carl Friedrich Lessing. The hallmarks of Düsseldorf painting at mid-century were accurate draftsmanship and truthful rendering of natural forms, applied equally to figures and to landscape. In the process of mastering this style, Bierstadt set out in the spring of 1854 to explore the Westphalian countryside and to make careful sketches that could become the sources for paintings. In <em>Landscape on the Rhine</em>, one of the drawings from that first sketching trip, Bierstadt described the yard of a cooperage on the banks of the Rhine. Using only pencil and opaque white wash, he coaxed a landscape from the uniform tan tone of a smooth-surfaced paper. The subject might have attracted Bierstadt for personal reasons: his father had emigrated from Germany as a cooper and continued to practice this trade in the United States. Set in a shallow cove, the scene provides a glimpse of local industry that adds distinctive genre elements to the landscape. While there are no descriptive signs of the workshop or forge, whole barrels are visible at left, and others with sprung rims, broken staves, and missing heads are scattered about the foreground. Bierstadt made numerous costume studies as part of his Düsseldorf training and used this knowledge to distinguish the figures in his compositions. Of the four men depicted here, the two wearing wide-brimmed black hats may have come from a nearby vineyard or granary to negotiate the purchase or repair of the barrels. The old stone structure, which could have served as the cooper’s shop, supplies the drawing with a picturesque focus and randomly separates sunlight from shadow through the boards of its wooden awning. Its humble profile stands in contrast to the sweeping cliffs that prefigure the dramatic settings of Bierstadt’s later work. Ruins, old mills, and barns were familiar motifs in landscape paintings. Fallen into decay, they suggested reunion with nature; when still in use, they depicted aspects of times past, or of rural commerce, which appealed to urban collectors. The drawing is carefully organized on the sheet—which is signed with Bierstadt’s monogram on a barrel at left, and dated—and projects a sense of completion. It may have been exchanged with a colleague or given to a friend or family member as a gift, although the primary purpose of drawings made on sketching trips was to serve as sources in the preparation of larger works. The abrupt definition of the cliffs along the shoreline, the effective elimination of middle distance, and the sketchy rendering of trees and grasses reinforce the fact that Bierstadt’s interest was directed to the foreground motif. Although not identified with a documented work, the vignette of the cooperage might have been included in one of the paintings of the following year that incorporated both genre elements and rustic architecture in broader landscape settings.Among the Düsseldorf subjects that included related architectural elements were Westphalian Landscape (1855, Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vermont), A Rustic Mill (1855, private collection; illustrated in Anderson and Ferber 1990, 125), and The Old Mill (1855, private collection; illustrated in Anderson and Ferber 1990, 128). Bierstadt’s method of accumulating numerous detailed sketches remained his modus operandi when he explored the American West. The precision of his Western views was also facilitated by photography, the profession adopted by his brothers Charles and Edward. With the destruction of Bierstadt’s Hudson River home and studio by fire in 1882, many of the drawings that he had made throughout his career were lost. Of those that remained in private hands, <em>Landscape on the Rhine</em> is a revealing document of his Düsseldorf training and his early skill as a draftsman. Landscape and Leisure: 19th-Century American Drawings from the Collection is on view at the RISD Museum from March 13 – July 19, 2015. Maureen O’Brien Curator of Painting and Sculpture ') (Line: 116) Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->process('Albert Bierstadt was born in Solingen, Germany, but came to the United States with his family in 1832 and settled with them in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Although details of his early artistic training are unknown, by 1850 he advertised himself as a teacher of “an improved system of monochromatic painting.”Nancy K. Anderson and Linda S. Ferber, in Albert Bierstadt: Art and Enterprise (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with the Brooklyn Museum, 1990), 115; their Chronology section notes the first advertisement of Bierstadt’s services in the New Bedford Standard of May 13, 1850, and cites Richard Schafer Trump, The Life and Works of Albert Bierstadt (dissertation, Ohio State University, 1963), 23, for quoting a broadside of June 6, 1850, promoting his “improved system.” The following year he added instruction in “Painting Colored Crayon Heads and Landscapes from nature, or from copies,” as well as “a new style of sketching from nature which can be acquired in one lesson.”Newport Daily News, June 7, 1851, cited in Anderson and Ferber 1990, 116. During the early 1850s, Bierstadt exhibited his work in Boston and collaborated with the American artist George Harvey on a light show that utilized the latter’s “dissolving views” of landscapes painted on glass.Anderson and Ferber, 116. In 1853 Bierstadt became a naturalized American citizen and returned to Germany to continue his own artistic education. When Bierstadt arrived in Europe he was disappointed to learn of the death of Johann Peter Hasenclever, the noted Düsseldorf genre painter with whom he had planned to study. He remained in that city, however, and although he did not officially enter the Düsseldorf Academy, he progressed quickly under the guidance of American colleagues Worthington Whittredge and Emanuel Leutze, the German landscape painter Andreas Achenbach, and the circle of artists around Carl Friedrich Lessing. The hallmarks of Düsseldorf painting at mid-century were accurate draftsmanship and truthful rendering of natural forms, applied equally to figures and to landscape. In the process of mastering this style, Bierstadt set out in the spring of 1854 to explore the Westphalian countryside and to make careful sketches that could become the sources for paintings. In <em>Landscape on the Rhine</em>, one of the drawings from that first sketching trip, Bierstadt described the yard of a cooperage on the banks of the Rhine. Using only pencil and opaque white wash, he coaxed a landscape from the uniform tan tone of a smooth-surfaced paper. The subject might have attracted Bierstadt for personal reasons: his father had emigrated from Germany as a cooper and continued to practice this trade in the United States. Set in a shallow cove, the scene provides a glimpse of local industry that adds distinctive genre elements to the landscape. While there are no descriptive signs of the workshop or forge, whole barrels are visible at left, and others with sprung rims, broken staves, and missing heads are scattered about the foreground. Bierstadt made numerous costume studies as part of his Düsseldorf training and used this knowledge to distinguish the figures in his compositions. Of the four men depicted here, the two wearing wide-brimmed black hats may have come from a nearby vineyard or granary to negotiate the purchase or repair of the barrels. The old stone structure, which could have served as the cooper’s shop, supplies the drawing with a picturesque focus and randomly separates sunlight from shadow through the boards of its wooden awning. Its humble profile stands in contrast to the sweeping cliffs that prefigure the dramatic settings of Bierstadt’s later work. Ruins, old mills, and barns were familiar motifs in landscape paintings. Fallen into decay, they suggested reunion with nature; when still in use, they depicted aspects of times past, or of rural commerce, which appealed to urban collectors. The drawing is carefully organized on the sheet—which is signed with Bierstadt’s monogram on a barrel at left, and dated—and projects a sense of completion. It may have been exchanged with a colleague or given to a friend or family member as a gift, although the primary purpose of drawings made on sketching trips was to serve as sources in the preparation of larger works. The abrupt definition of the cliffs along the shoreline, the effective elimination of middle distance, and the sketchy rendering of trees and grasses reinforce the fact that Bierstadt’s interest was directed to the foreground motif. Although not identified with a documented work, the vignette of the cooperage might have been included in one of the paintings of the following year that incorporated both genre elements and rustic architecture in broader landscape settings.Among the Düsseldorf subjects that included related architectural elements were Westphalian Landscape (1855, Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vermont), A Rustic Mill (1855, private collection; illustrated in Anderson and Ferber 1990, 125), and The Old Mill (1855, private collection; illustrated in Anderson and Ferber 1990, 128). Bierstadt’s method of accumulating numerous detailed sketches remained his modus operandi when he explored the American West. The precision of his Western views was also facilitated by photography, the profession adopted by his brothers Charles and Edward. With the destruction of Bierstadt’s Hudson River home and studio by fire in 1882, many of the drawings that he had made throughout his career were lost. Of those that remained in private hands, <em>Landscape on the Rhine</em> is a revealing document of his Düsseldorf training and his early skill as a draftsman. Landscape and Leisure: 19th-Century American Drawings from the Collection is on view at the RISD Museum from March 13 – July 19, 2015. Maureen O’Brien Curator of Painting and Sculpture ', 'en') (Line: 118) Drupal\filter\Element\ProcessedText::preRenderText(Array) call_user_func_array(Array, Array) (Line: 111) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doTrustedCallback(Array, Array, 'Render #pre_render callbacks must be methods of a class that implements \Drupal\Core\Security\TrustedCallbackInterface or be an anonymous function. The callback was %s. See https://www.drupal.org/node/2966725', 'exception', 'Drupal\Core\Render\Element\RenderCallbackInterface') (Line: 797) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doCallback('#pre_render', Array, Array) (Line: 386) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 106) __TwigTemplate_4039b6d648e4a30fc59604b38849a688->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 46) __TwigTemplate_d1494d795b4bd5366283e85f3e7729dc->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 43) __TwigTemplate_253b62141ad73ee07345b0067cf59829->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/contrib/classy/templates/field/field--text-with-summary.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('field', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 231) __TwigTemplate_d0a4e06ec4cdc862487a9e59e7ee55e6->block_node_content(Array, Array) (Line: 171) Twig\Template->displayBlock('node_content', Array, Array) (Line: 91) __TwigTemplate_fb45c12c057c90d6dad87acc3f8af627->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 51) __TwigTemplate_d0a4e06ec4cdc862487a9e59e7ee55e6->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/content/node--teaser.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('node', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 60) __TwigTemplate_b5820ae2fc9ac809d8bb920432eaa798->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/contrib/classy/templates/views/views-view-unformatted.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('views_view_unformatted', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 129) __TwigTemplate_c1babb60e112ad993125dc5af5a5b779->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/views/views-view--site-search--page-1.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('views_view__site_search__page_1', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array, ) (Line: 238) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\{closure}() (Line: 592) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->executeInRenderContext(Object, Object) (Line: 239) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->prepare(Array, Object, Object) (Line: 128) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->renderResponse(Array, Object, Object) (Line: 90) Drupal\Core\EventSubscriber\MainContentViewSubscriber->onViewRenderArray(Object, 'kernel.view', Object) call_user_func(Array, Object, 'kernel.view', Object) (Line: 111) Drupal\Component\EventDispatcher\ContainerAwareEventDispatcher->dispatch(Object, 'kernel.view') (Line: 186) Symfony\Component\HttpKernel\HttpKernel->handleRaw(Object, 1) (Line: 76) Symfony\Component\HttpKernel\HttpKernel->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 58) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\Session->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 48) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\KernelPreHandle->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 191) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->fetch(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 128) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->lookup(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 82) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 270) Drupal\shield\ShieldMiddleware->bypass(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 137) Drupal\shield\ShieldMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 48) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\ReverseProxyMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 51) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\NegotiationMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 51) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\StackedHttpKernel->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 704) Drupal\Core\DrupalKernel->handle(Object) (Line: 19) - Warning: Undefined array key 0 in Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances() (line 392 of modules/contrib/footnotes/src/Plugin/Filter/FootnotesFilter.php).

Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances('Albert Bierstadt was born in Solingen, Germany, but came to the United States with his family in 1832 and settled with them in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Although details of his early artistic training are unknown, by 1850 he advertised himself as a teacher of “an improved system of monochromatic painting.”Nancy K. Anderson and Linda S. Ferber, in Albert Bierstadt: Art and Enterprise (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with the Brooklyn Museum, 1990), 115; their Chronology section notes the first advertisement of Bierstadt’s services in the New Bedford Standard of May 13, 1850, and cites Richard Schafer Trump, The Life and Works of Albert Bierstadt (dissertation, Ohio State University, 1963), 23, for quoting a broadside of June 6, 1850, promoting his “improved system.” The following year he added instruction in “Painting Colored Crayon Heads and Landscapes from nature, or from copies,” as well as “a new style of sketching from nature which can be acquired in one lesson.”Newport Daily News, June 7, 1851, cited in Anderson and Ferber 1990, 116. During the early 1850s, Bierstadt exhibited his work in Boston and collaborated with the American artist George Harvey on a light show that utilized the latter’s “dissolving views” of landscapes painted on glass.Anderson and Ferber, 116. In 1853 Bierstadt became a naturalized American citizen and returned to Germany to continue his own artistic education. When Bierstadt arrived in Europe he was disappointed to learn of the death of Johann Peter Hasenclever, the noted Düsseldorf genre painter with whom he had planned to study. He remained in that city, however, and although he did not officially enter the Düsseldorf Academy, he progressed quickly under the guidance of American colleagues Worthington Whittredge and Emanuel Leutze, the German landscape painter Andreas Achenbach, and the circle of artists around Carl Friedrich Lessing. The hallmarks of Düsseldorf painting at mid-century were accurate draftsmanship and truthful rendering of natural forms, applied equally to figures and to landscape. In the process of mastering this style, Bierstadt set out in the spring of 1854 to explore the Westphalian countryside and to make careful sketches that could become the sources for paintings. In <em>Landscape on the Rhine</em>, one of the drawings from that first sketching trip, Bierstadt described the yard of a cooperage on the banks of the Rhine. Using only pencil and opaque white wash, he coaxed a landscape from the uniform tan tone of a smooth-surfaced paper. The subject might have attracted Bierstadt for personal reasons: his father had emigrated from Germany as a cooper and continued to practice this trade in the United States. Set in a shallow cove, the scene provides a glimpse of local industry that adds distinctive genre elements to the landscape. While there are no descriptive signs of the workshop or forge, whole barrels are visible at left, and others with sprung rims, broken staves, and missing heads are scattered about the foreground. Bierstadt made numerous costume studies as part of his Düsseldorf training and used this knowledge to distinguish the figures in his compositions. Of the four men depicted here, the two wearing wide-brimmed black hats may have come from a nearby vineyard or granary to negotiate the purchase or repair of the barrels. The old stone structure, which could have served as the cooper’s shop, supplies the drawing with a picturesque focus and randomly separates sunlight from shadow through the boards of its wooden awning. Its humble profile stands in contrast to the sweeping cliffs that prefigure the dramatic settings of Bierstadt’s later work. Ruins, old mills, and barns were familiar motifs in landscape paintings. Fallen into decay, they suggested reunion with nature; when still in use, they depicted aspects of times past, or of rural commerce, which appealed to urban collectors. The drawing is carefully organized on the sheet—which is signed with Bierstadt’s monogram on a barrel at left, and dated—and projects a sense of completion. It may have been exchanged with a colleague or given to a friend or family member as a gift, although the primary purpose of drawings made on sketching trips was to serve as sources in the preparation of larger works. The abrupt definition of the cliffs along the shoreline, the effective elimination of middle distance, and the sketchy rendering of trees and grasses reinforce the fact that Bierstadt’s interest was directed to the foreground motif. Although not identified with a documented work, the vignette of the cooperage might have been included in one of the paintings of the following year that incorporated both genre elements and rustic architecture in broader landscape settings.Among the Düsseldorf subjects that included related architectural elements were Westphalian Landscape (1855, Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vermont), A Rustic Mill (1855, private collection; illustrated in Anderson and Ferber 1990, 125), and The Old Mill (1855, private collection; illustrated in Anderson and Ferber 1990, 128). Bierstadt’s method of accumulating numerous detailed sketches remained his modus operandi when he explored the American West. The precision of his Western views was also facilitated by photography, the profession adopted by his brothers Charles and Edward. With the destruction of Bierstadt’s Hudson River home and studio by fire in 1882, many of the drawings that he had made throughout his career were lost. Of those that remained in private hands, <em>Landscape on the Rhine</em> is a revealing document of his Düsseldorf training and his early skill as a draftsman. Landscape and Leisure: 19th-Century American Drawings from the Collection is on view at the RISD Museum from March 13 – July 19, 2015. Maureen O’Brien Curator of Painting and Sculpture ') (Line: 116) Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->process('Albert Bierstadt was born in Solingen, Germany, but came to the United States with his family in 1832 and settled with them in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Although details of his early artistic training are unknown, by 1850 he advertised himself as a teacher of “an improved system of monochromatic painting.”Nancy K. Anderson and Linda S. Ferber, in Albert Bierstadt: Art and Enterprise (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with the Brooklyn Museum, 1990), 115; their Chronology section notes the first advertisement of Bierstadt’s services in the New Bedford Standard of May 13, 1850, and cites Richard Schafer Trump, The Life and Works of Albert Bierstadt (dissertation, Ohio State University, 1963), 23, for quoting a broadside of June 6, 1850, promoting his “improved system.” The following year he added instruction in “Painting Colored Crayon Heads and Landscapes from nature, or from copies,” as well as “a new style of sketching from nature which can be acquired in one lesson.”Newport Daily News, June 7, 1851, cited in Anderson and Ferber 1990, 116. During the early 1850s, Bierstadt exhibited his work in Boston and collaborated with the American artist George Harvey on a light show that utilized the latter’s “dissolving views” of landscapes painted on glass.Anderson and Ferber, 116. In 1853 Bierstadt became a naturalized American citizen and returned to Germany to continue his own artistic education. When Bierstadt arrived in Europe he was disappointed to learn of the death of Johann Peter Hasenclever, the noted Düsseldorf genre painter with whom he had planned to study. He remained in that city, however, and although he did not officially enter the Düsseldorf Academy, he progressed quickly under the guidance of American colleagues Worthington Whittredge and Emanuel Leutze, the German landscape painter Andreas Achenbach, and the circle of artists around Carl Friedrich Lessing. The hallmarks of Düsseldorf painting at mid-century were accurate draftsmanship and truthful rendering of natural forms, applied equally to figures and to landscape. In the process of mastering this style, Bierstadt set out in the spring of 1854 to explore the Westphalian countryside and to make careful sketches that could become the sources for paintings. In <em>Landscape on the Rhine</em>, one of the drawings from that first sketching trip, Bierstadt described the yard of a cooperage on the banks of the Rhine. Using only pencil and opaque white wash, he coaxed a landscape from the uniform tan tone of a smooth-surfaced paper. The subject might have attracted Bierstadt for personal reasons: his father had emigrated from Germany as a cooper and continued to practice this trade in the United States. Set in a shallow cove, the scene provides a glimpse of local industry that adds distinctive genre elements to the landscape. While there are no descriptive signs of the workshop or forge, whole barrels are visible at left, and others with sprung rims, broken staves, and missing heads are scattered about the foreground. Bierstadt made numerous costume studies as part of his Düsseldorf training and used this knowledge to distinguish the figures in his compositions. Of the four men depicted here, the two wearing wide-brimmed black hats may have come from a nearby vineyard or granary to negotiate the purchase or repair of the barrels. The old stone structure, which could have served as the cooper’s shop, supplies the drawing with a picturesque focus and randomly separates sunlight from shadow through the boards of its wooden awning. Its humble profile stands in contrast to the sweeping cliffs that prefigure the dramatic settings of Bierstadt’s later work. Ruins, old mills, and barns were familiar motifs in landscape paintings. Fallen into decay, they suggested reunion with nature; when still in use, they depicted aspects of times past, or of rural commerce, which appealed to urban collectors. The drawing is carefully organized on the sheet—which is signed with Bierstadt’s monogram on a barrel at left, and dated—and projects a sense of completion. It may have been exchanged with a colleague or given to a friend or family member as a gift, although the primary purpose of drawings made on sketching trips was to serve as sources in the preparation of larger works. The abrupt definition of the cliffs along the shoreline, the effective elimination of middle distance, and the sketchy rendering of trees and grasses reinforce the fact that Bierstadt’s interest was directed to the foreground motif. Although not identified with a documented work, the vignette of the cooperage might have been included in one of the paintings of the following year that incorporated both genre elements and rustic architecture in broader landscape settings.Among the Düsseldorf subjects that included related architectural elements were Westphalian Landscape (1855, Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vermont), A Rustic Mill (1855, private collection; illustrated in Anderson and Ferber 1990, 125), and The Old Mill (1855, private collection; illustrated in Anderson and Ferber 1990, 128). Bierstadt’s method of accumulating numerous detailed sketches remained his modus operandi when he explored the American West. The precision of his Western views was also facilitated by photography, the profession adopted by his brothers Charles and Edward. With the destruction of Bierstadt’s Hudson River home and studio by fire in 1882, many of the drawings that he had made throughout his career were lost. Of those that remained in private hands, <em>Landscape on the Rhine</em> is a revealing document of his Düsseldorf training and his early skill as a draftsman. Landscape and Leisure: 19th-Century American Drawings from the Collection is on view at the RISD Museum from March 13 – July 19, 2015. Maureen O’Brien Curator of Painting and Sculpture ', 'en') (Line: 118) Drupal\filter\Element\ProcessedText::preRenderText(Array) call_user_func_array(Array, Array) (Line: 111) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doTrustedCallback(Array, Array, 'Render #pre_render callbacks must be methods of a class that implements \Drupal\Core\Security\TrustedCallbackInterface or be an anonymous function. The callback was %s. See https://www.drupal.org/node/2966725', 'exception', 'Drupal\Core\Render\Element\RenderCallbackInterface') (Line: 797) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doCallback('#pre_render', Array, Array) (Line: 386) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 106) __TwigTemplate_4039b6d648e4a30fc59604b38849a688->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 46) __TwigTemplate_d1494d795b4bd5366283e85f3e7729dc->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 43) __TwigTemplate_253b62141ad73ee07345b0067cf59829->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/contrib/classy/templates/field/field--text-with-summary.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('field', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 231) __TwigTemplate_d0a4e06ec4cdc862487a9e59e7ee55e6->block_node_content(Array, Array) (Line: 171) Twig\Template->displayBlock('node_content', Array, Array) (Line: 91) __TwigTemplate_fb45c12c057c90d6dad87acc3f8af627->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 51) __TwigTemplate_d0a4e06ec4cdc862487a9e59e7ee55e6->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/content/node--teaser.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('node', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 60) __TwigTemplate_b5820ae2fc9ac809d8bb920432eaa798->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/contrib/classy/templates/views/views-view-unformatted.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('views_view_unformatted', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 129) __TwigTemplate_c1babb60e112ad993125dc5af5a5b779->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/views/views-view--site-search--page-1.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('views_view__site_search__page_1', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array, ) (Line: 238) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\{closure}() (Line: 592) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->executeInRenderContext(Object, Object) (Line: 239) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->prepare(Array, Object, Object) (Line: 128) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->renderResponse(Array, Object, Object) (Line: 90) Drupal\Core\EventSubscriber\MainContentViewSubscriber->onViewRenderArray(Object, 'kernel.view', Object) call_user_func(Array, Object, 'kernel.view', Object) (Line: 111) Drupal\Component\EventDispatcher\ContainerAwareEventDispatcher->dispatch(Object, 'kernel.view') (Line: 186) Symfony\Component\HttpKernel\HttpKernel->handleRaw(Object, 1) (Line: 76) Symfony\Component\HttpKernel\HttpKernel->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 58) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\Session->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 48) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\KernelPreHandle->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 191) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->fetch(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 128) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->lookup(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 82) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 270) Drupal\shield\ShieldMiddleware->bypass(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 137) Drupal\shield\ShieldMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 48) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\ReverseProxyMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 51) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\NegotiationMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 51) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\StackedHttpKernel->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 704) Drupal\Core\DrupalKernel->handle(Object) (Line: 19) - Warning: Undefined array key 0 in Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances() (line 388 of modules/contrib/footnotes/src/Plugin/Filter/FootnotesFilter.php).