Error message

- Warning: Undefined array key 0 in Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances() (line 388 of modules/contrib/footnotes/src/Plugin/Filter/FootnotesFilter.php).

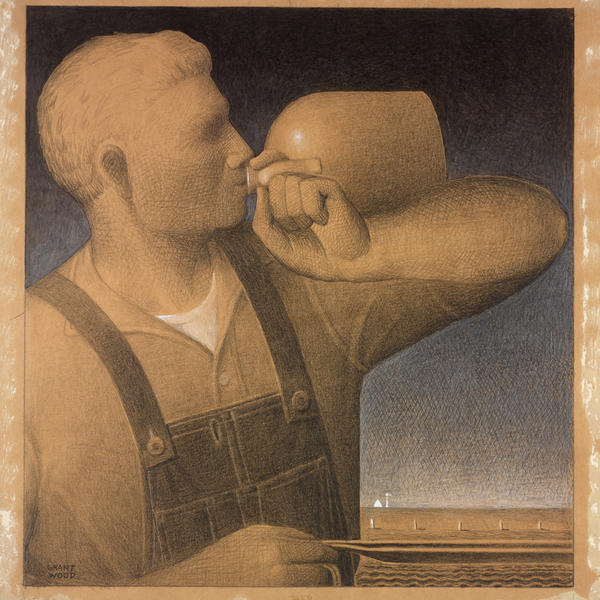

Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances('<em>Plowing on Sunday</em>, from about 1934The drawing is undated, but the image appeared on the cover of the first edition of Sterling North’s novel Plowing on Sunday (New York: Macmillan, 1934)., was described as Grant Wood’s “finest drawing to date” when it was offered to the RISD Museum for consideration in 1937Letter from Maynard Walker, Walker Galleries, New York, to Constance M. Place, Museum of Art, RISD, February 25, 1937. The drawing was purchased by the Museum president, Mrs. Murray Danforth, for $750, a sum that reflected the limited number and availability of Wood’s works at this time. Mrs. Danforth officially made the drawing a gift to the Museum in January 1938.. The squared-off close-up of a farmer drinking from an earthenware jug was purchased by RISD’s president, Helen M. Danforth, who gave it to the collection the following year, around the time Wood visited Providence. Speaking to a capacity crowd at RISD’s Memorial Hall on a January evening, Wood stressed the importance of regional art schools and expressed his belief that small groups were now merging to make a more democratic national artWood’s lecture, which was introduced by painter John Frazier to a “large audience of artists, art students, and art lovers,” was reported in the Providence Journal article “American Artist Speaks of Work: Grant Wood, Midwestern Painter, Addresses Group at Design School,” January 22, 1938. In a letter to RISD president Mrs. Murray Danforth, former interim director Miriam Banks reported: “I have never seen Memorial Hall crowded to such capacity before on any like occasion. Every available seat on the floor was taken and the gallery filled also” (RISD Archives, Directors’ Correspondence files).. Although a leading painter of the American scene, Wood was careful to distinguish between art that advocated “a concentration on local peculiarities” and one that acknowledged important differences between the various regions of AmericaIn 1937, Wood commented on American literary regionalism, stating that “it has been a revolt against cultural nationalism—that is the tendency of artists to ignore or deny the fact that there are important differences, psychologically and otherwise, between the various regions of America. But this does not mean that Regionalism, in turn, advocates a concentration on local peculiarities; such an approach results in anecdotalism and local color” (handwritten commentary on a typed proposal by “the members of English 293, October, 1937,” Grant Wood Scrapbook 02, Grant Wood 1935–1939; University of Iowa Libraries, Figge Art Museum Grant Wood Digital Collection).. He de-emphasized the term “Regionalism” in his RISD talk, insisting it was “not geographic accent but sincere emotion and vitality that distinguish fine painting.”From The Providence Journal, January 22, 1938: “The movement, exemplified by such men as Charles Burchfield, John Steuart Curry, Reginald Marsh and Thomas Benton, who were through their individual techniques each expressing his particular environment was given the name Regionalism. Mr. Wood feels that since it is not geographic accent but sincere emotion and vitality which distinguish fine painting, the term Regionalism is unfortunate.” By 1938, Wood was widely recognized for the narrative appeal of paintings such as <a href="http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/artwork/6565"><em>American Gothic</em></a>, his apotropaic depiction of a father and daughter in front of their Iowa farmhouse. But Wood had long explored more abstract formal solutions in his pursuit of an original style that embraced native subject matter. In <em>Plowing on Sunday</em>, he elevated the figure in importance but diminished individuality in favor of a simplified composition that embedded universal qualities in an American motif. Later, in his 1936 painting <a href="https://reynoldahouse.emuseum.com/objects/12/spring-turning"><em>Spring Turning</em></a>, he reduced the farmer and plow to mere notations, stitching them to the edge of the green and brown quilt of a sculpted Midwestern landscape. Commissioned as the cover design for Sterling North’s eponymous 1934 novel, <em>Plowing on Sunday</em> depicted Stud Brailsford, “a strong man whose wishes and fancies and material ambitions are real and on a human scale.”K. W. (Kenneth White?), review of Sterling North, Plowing on Sunday, in The Saturday Review of Literature, December 15, 1934, 374. North had described Brailsford as a man with a leonine head and mass of graying curls, but the light wavy hair, high cheekbones, and square jaw of Wood’s plowman read as a stylized adaptation of <a href="https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/items/detail/john-steuart-curry-and-grant-wood-8657">the artist’s own features</a>.Wood appears in his preferred attire in a photograph with fellow artist John Steuart Curry, ca. 1932. (Accessible at https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/items/detail/john-steuart-curry-and-grant-wood-8657.) It is related to <a href="http://www.crma.org/Content/Collection/Grant-Wood.aspx">a self-portrait Wood drew in 1932</a>, in which he appeared next to a windmill, wearing the bib overalls he favored.Wood wears a light-colored shirt and bib overalls in his 1932 Self-Portrait (charcoal and pastel on paper; 14 1/2 x 12 in.; Cedar Rapids Art Museum, Cedar Rapids, Iowa), accessible at http://www.crma.org/Content/Collection/Grant-Wood.aspx. This drawing appears to be the study for a painted Self Portrait, 1932–1941 (oil on Masonite panel, 14 3/4 x 12 3/8 in., Figge Art Museum, Davenport, Iowa), in which he appears in a dark shirt. (Accessible at http://figgeartmuseum.org/getattachment/e7bb49f1-d08c-45d2-882e-575d14f729a4/Self-Portrait-65-0001.aspx?maxsidesize=300.) For both drawings he used brown paper as the support, utilizing its color to achieve an overall earth-tone that unified the composition and reinforced the connection between the figure and the land. In <em>Plowing on Sunday</em>, he restricted his media to black conté crayon, ink, and gouache, which he effectively mixed to suggest indigo. Fine webs of diagonal cross-hatching suggest weight, density, and light. Wood varies these patterns to brighten the horizon and to model the plowman’s arms and face. Elsewhere, by deftly shifting his additive technique to imperceptible directional marks, he coaxes an appearance of “tooth” from the smooth paper to create a softer, fabric-like effect for the shirt and denim overalls. In the upper sky, Wood maximizes the coverage of his medium to generate a darkened sky and to force the sharp outlines of the head and water jug into relief. Rendered in a technique that recalls Georges Seurat’s landscape and figural compositions, the plowman emerges as a stoic, sculptural form in an artistic genealogy that ranges from Giotto’s solid peasants to the working men of WPA friezes. Brady M. Roberts notes parallels between Wood’s techniques and those of Seurat in the essay “The European Roots of Regionalism” in Grant Wood: An American Master Revealed (Portland, Oregon: Pomegranate, 1995), 2. In note 9 on page 227 of When Tillage Begins, Other Arts Follow: Grant Wood and Christian Petersen Murals (Ames, Iowa: University Museums, Iowa State University, 2006), Lea Rosson DeLong cites a letter from Wood’s student Leata Rowan, who wrote that Giotto was one of the artists whom Wood taught in his classes on mural painting at the University of Iowa (January 12, 1934, Papers of Edward Rowan, Archives of American Art, reel D 141, fr. 89-01). Paul Signac quoted Edgar Degas’s comment to Seurat upon viewing La Grande Jatte: “You have been in Florence, you have. You have seen the Giottos” (cited by Robert L. Herbert, Georges Seurat, 1859–1891, 174 [New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art and Abrams, 1991]). This effect reinforces the plowman’s connection to his environment and confers a sense of action frozen in time. Wood’s use of brown wrapping paper for both finished drawings and mural preparation was intentional, and he advised his students to use this inexpensive material to encourage experimentation. In 1934 he developed <a href="http://archive.inside.iastate.edu/2004/0116/wood.shtml">a suite of illustrations on brown paper</a> for a limited edition of Sinclair Lewis’s novel <em>Main Street</em>, and showed slides of those drawings at the RISD lecture.The Providence Journal, op. cit., reported that Wood showed slides of his works, including the Main Street illustrations, following the RISD lecture. That commission is Lea Rosson Delong’s subject in Grant Wood’s Main Street: Art, Literature, and the American Midwest (Ames, Iowa: University Museums, Iowa State University, 2004). Like the plowman’s, the heads and upper torsos of Lewis’s characters nearly fill their frames, and their hands and arms indicate representative gestures. While their expressions reveal distinct personalities, the plowman, in contrast, has veiled eyes and no psychologically distinguishing characteristics other than the strong contours of the face and head. By minimizing detail, as he did in his paintings of the late 1930s, Wood transformed his own likeness into a plowman who is Everyman, dressed in the farm uniform that was both democratic and anonymous in its ubiquity. In keeping with his program of simplification, Wood further reduced the imagery of <em>Plowing on Sunday</em> by eliminating the plow, the tool that served as both the icon and metaphor for the activity of tilling the earth. In <em>Plowing on Sunday</em> he introduces the reins at the lower corner of the picture to imply both the farm animals and the instrument they control, and uses the field and low horizon to reinforce the symbolic and decorative value of the leather straps. He follows their taut lines with a wavy pattern of plowed furrows and marks the border of the field with a parallel march of tiny white fence posts. Barely visible on the horizon are a classic Iowa barn and windmill, selective decorative marks that are intentional references to the rural architecture whose extinction Wood feared.The windmill is a prominent element in the two self-portraits made by Wood (cited in endnote 7). Wanda Corn, on page 126 of Grant Wood: The Regionalist Vision (New Haven: Minneapolis Museum of Art and Yale University Press, 1983), notes that Wood “had become particularly attached to the windmill, a familiar landmark in the Midwest, which he feared was becoming extinct,” and that he always found a way to work it into his compositions as a type of signature. Wood re-utilized and expanded the plowman image after he became director of the Iowa’s Public Works of Art Projects in 1934. A full-scale variant of the farmer, posed with his plow and its resting team of horses, drinks from a water jug in the central panel of <em>Breaking the Prairie Sod</em>, Wood’s mural cycle for the Iowa State University Library at Ames.Breaking the Prairie, 1937 (oil on canvas, center panel: 132 x 279 in.; The Iowa State University Library, Ames, Iowa; accessible at https://isuartandhistory.files.wordpress.com/2011/06/copy-of-images-014.jpg). There is also a finished drawing for this mural: Breaking the Prairie, ca. 1935–1937 (colored pencil, chalk, and pencil on brown paper; 22 3/4 x 80 1/4 in.; The Whitney Museum of American Art, Gift of Mr. & Mrs. George D. Stoddard). <em>Maureen O’Brien Curator, Painting and Sculpture</em> ') (Line: 116) Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->process('<em>Plowing on Sunday</em>, from about 1934The drawing is undated, but the image appeared on the cover of the first edition of Sterling North’s novel Plowing on Sunday (New York: Macmillan, 1934)., was described as Grant Wood’s “finest drawing to date” when it was offered to the RISD Museum for consideration in 1937Letter from Maynard Walker, Walker Galleries, New York, to Constance M. Place, Museum of Art, RISD, February 25, 1937. The drawing was purchased by the Museum president, Mrs. Murray Danforth, for $750, a sum that reflected the limited number and availability of Wood’s works at this time. Mrs. Danforth officially made the drawing a gift to the Museum in January 1938.. The squared-off close-up of a farmer drinking from an earthenware jug was purchased by RISD’s president, Helen M. Danforth, who gave it to the collection the following year, around the time Wood visited Providence. Speaking to a capacity crowd at RISD’s Memorial Hall on a January evening, Wood stressed the importance of regional art schools and expressed his belief that small groups were now merging to make a more democratic national artWood’s lecture, which was introduced by painter John Frazier to a “large audience of artists, art students, and art lovers,” was reported in the Providence Journal article “American Artist Speaks of Work: Grant Wood, Midwestern Painter, Addresses Group at Design School,” January 22, 1938. In a letter to RISD president Mrs. Murray Danforth, former interim director Miriam Banks reported: “I have never seen Memorial Hall crowded to such capacity before on any like occasion. Every available seat on the floor was taken and the gallery filled also” (RISD Archives, Directors’ Correspondence files).. Although a leading painter of the American scene, Wood was careful to distinguish between art that advocated “a concentration on local peculiarities” and one that acknowledged important differences between the various regions of AmericaIn 1937, Wood commented on American literary regionalism, stating that “it has been a revolt against cultural nationalism—that is the tendency of artists to ignore or deny the fact that there are important differences, psychologically and otherwise, between the various regions of America. But this does not mean that Regionalism, in turn, advocates a concentration on local peculiarities; such an approach results in anecdotalism and local color” (handwritten commentary on a typed proposal by “the members of English 293, October, 1937,” Grant Wood Scrapbook 02, Grant Wood 1935–1939; University of Iowa Libraries, Figge Art Museum Grant Wood Digital Collection).. He de-emphasized the term “Regionalism” in his RISD talk, insisting it was “not geographic accent but sincere emotion and vitality that distinguish fine painting.”From The Providence Journal, January 22, 1938: “The movement, exemplified by such men as Charles Burchfield, John Steuart Curry, Reginald Marsh and Thomas Benton, who were through their individual techniques each expressing his particular environment was given the name Regionalism. Mr. Wood feels that since it is not geographic accent but sincere emotion and vitality which distinguish fine painting, the term Regionalism is unfortunate.” By 1938, Wood was widely recognized for the narrative appeal of paintings such as <a href="http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/artwork/6565"><em>American Gothic</em></a>, his apotropaic depiction of a father and daughter in front of their Iowa farmhouse. But Wood had long explored more abstract formal solutions in his pursuit of an original style that embraced native subject matter. In <em>Plowing on Sunday</em>, he elevated the figure in importance but diminished individuality in favor of a simplified composition that embedded universal qualities in an American motif. Later, in his 1936 painting <a href="https://reynoldahouse.emuseum.com/objects/12/spring-turning"><em>Spring Turning</em></a>, he reduced the farmer and plow to mere notations, stitching them to the edge of the green and brown quilt of a sculpted Midwestern landscape. Commissioned as the cover design for Sterling North’s eponymous 1934 novel, <em>Plowing on Sunday</em> depicted Stud Brailsford, “a strong man whose wishes and fancies and material ambitions are real and on a human scale.”K. W. (Kenneth White?), review of Sterling North, Plowing on Sunday, in The Saturday Review of Literature, December 15, 1934, 374. North had described Brailsford as a man with a leonine head and mass of graying curls, but the light wavy hair, high cheekbones, and square jaw of Wood’s plowman read as a stylized adaptation of <a href="https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/items/detail/john-steuart-curry-and-grant-wood-8657">the artist’s own features</a>.Wood appears in his preferred attire in a photograph with fellow artist John Steuart Curry, ca. 1932. (Accessible at https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/items/detail/john-steuart-curry-and-grant-wood-8657.) It is related to <a href="http://www.crma.org/Content/Collection/Grant-Wood.aspx">a self-portrait Wood drew in 1932</a>, in which he appeared next to a windmill, wearing the bib overalls he favored.Wood wears a light-colored shirt and bib overalls in his 1932 Self-Portrait (charcoal and pastel on paper; 14 1/2 x 12 in.; Cedar Rapids Art Museum, Cedar Rapids, Iowa), accessible at http://www.crma.org/Content/Collection/Grant-Wood.aspx. This drawing appears to be the study for a painted Self Portrait, 1932–1941 (oil on Masonite panel, 14 3/4 x 12 3/8 in., Figge Art Museum, Davenport, Iowa), in which he appears in a dark shirt. (Accessible at http://figgeartmuseum.org/getattachment/e7bb49f1-d08c-45d2-882e-575d14f729a4/Self-Portrait-65-0001.aspx?maxsidesize=300.) For both drawings he used brown paper as the support, utilizing its color to achieve an overall earth-tone that unified the composition and reinforced the connection between the figure and the land. In <em>Plowing on Sunday</em>, he restricted his media to black conté crayon, ink, and gouache, which he effectively mixed to suggest indigo. Fine webs of diagonal cross-hatching suggest weight, density, and light. Wood varies these patterns to brighten the horizon and to model the plowman’s arms and face. Elsewhere, by deftly shifting his additive technique to imperceptible directional marks, he coaxes an appearance of “tooth” from the smooth paper to create a softer, fabric-like effect for the shirt and denim overalls. In the upper sky, Wood maximizes the coverage of his medium to generate a darkened sky and to force the sharp outlines of the head and water jug into relief. Rendered in a technique that recalls Georges Seurat’s landscape and figural compositions, the plowman emerges as a stoic, sculptural form in an artistic genealogy that ranges from Giotto’s solid peasants to the working men of WPA friezes. Brady M. Roberts notes parallels between Wood’s techniques and those of Seurat in the essay “The European Roots of Regionalism” in Grant Wood: An American Master Revealed (Portland, Oregon: Pomegranate, 1995), 2. In note 9 on page 227 of When Tillage Begins, Other Arts Follow: Grant Wood and Christian Petersen Murals (Ames, Iowa: University Museums, Iowa State University, 2006), Lea Rosson DeLong cites a letter from Wood’s student Leata Rowan, who wrote that Giotto was one of the artists whom Wood taught in his classes on mural painting at the University of Iowa (January 12, 1934, Papers of Edward Rowan, Archives of American Art, reel D 141, fr. 89-01). Paul Signac quoted Edgar Degas’s comment to Seurat upon viewing La Grande Jatte: “You have been in Florence, you have. You have seen the Giottos” (cited by Robert L. Herbert, Georges Seurat, 1859–1891, 174 [New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art and Abrams, 1991]). This effect reinforces the plowman’s connection to his environment and confers a sense of action frozen in time. Wood’s use of brown wrapping paper for both finished drawings and mural preparation was intentional, and he advised his students to use this inexpensive material to encourage experimentation. In 1934 he developed <a href="http://archive.inside.iastate.edu/2004/0116/wood.shtml">a suite of illustrations on brown paper</a> for a limited edition of Sinclair Lewis’s novel <em>Main Street</em>, and showed slides of those drawings at the RISD lecture.The Providence Journal, op. cit., reported that Wood showed slides of his works, including the Main Street illustrations, following the RISD lecture. That commission is Lea Rosson Delong’s subject in Grant Wood’s Main Street: Art, Literature, and the American Midwest (Ames, Iowa: University Museums, Iowa State University, 2004). Like the plowman’s, the heads and upper torsos of Lewis’s characters nearly fill their frames, and their hands and arms indicate representative gestures. While their expressions reveal distinct personalities, the plowman, in contrast, has veiled eyes and no psychologically distinguishing characteristics other than the strong contours of the face and head. By minimizing detail, as he did in his paintings of the late 1930s, Wood transformed his own likeness into a plowman who is Everyman, dressed in the farm uniform that was both democratic and anonymous in its ubiquity. In keeping with his program of simplification, Wood further reduced the imagery of <em>Plowing on Sunday</em> by eliminating the plow, the tool that served as both the icon and metaphor for the activity of tilling the earth. In <em>Plowing on Sunday</em> he introduces the reins at the lower corner of the picture to imply both the farm animals and the instrument they control, and uses the field and low horizon to reinforce the symbolic and decorative value of the leather straps. He follows their taut lines with a wavy pattern of plowed furrows and marks the border of the field with a parallel march of tiny white fence posts. Barely visible on the horizon are a classic Iowa barn and windmill, selective decorative marks that are intentional references to the rural architecture whose extinction Wood feared.The windmill is a prominent element in the two self-portraits made by Wood (cited in endnote 7). Wanda Corn, on page 126 of Grant Wood: The Regionalist Vision (New Haven: Minneapolis Museum of Art and Yale University Press, 1983), notes that Wood “had become particularly attached to the windmill, a familiar landmark in the Midwest, which he feared was becoming extinct,” and that he always found a way to work it into his compositions as a type of signature. Wood re-utilized and expanded the plowman image after he became director of the Iowa’s Public Works of Art Projects in 1934. A full-scale variant of the farmer, posed with his plow and its resting team of horses, drinks from a water jug in the central panel of <em>Breaking the Prairie Sod</em>, Wood’s mural cycle for the Iowa State University Library at Ames.Breaking the Prairie, 1937 (oil on canvas, center panel: 132 x 279 in.; The Iowa State University Library, Ames, Iowa; accessible at https://isuartandhistory.files.wordpress.com/2011/06/copy-of-images-014.jpg). There is also a finished drawing for this mural: Breaking the Prairie, ca. 1935–1937 (colored pencil, chalk, and pencil on brown paper; 22 3/4 x 80 1/4 in.; The Whitney Museum of American Art, Gift of Mr. & Mrs. George D. Stoddard). <em>Maureen O’Brien Curator, Painting and Sculpture</em> ', 'en') (Line: 118) Drupal\filter\Element\ProcessedText::preRenderText(Array) call_user_func_array(Array, Array) (Line: 111) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doTrustedCallback(Array, Array, 'Render #pre_render callbacks must be methods of a class that implements \Drupal\Core\Security\TrustedCallbackInterface or be an anonymous function. The callback was %s. See https://www.drupal.org/node/2966725', 'exception', 'Drupal\Core\Render\Element\RenderCallbackInterface') (Line: 797) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doCallback('#pre_render', Array, Array) (Line: 386) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 106) __TwigTemplate_4039b6d648e4a30fc59604b38849a688->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 46) __TwigTemplate_d1494d795b4bd5366283e85f3e7729dc->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 43) __TwigTemplate_253b62141ad73ee07345b0067cf59829->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/contrib/classy/templates/field/field--text-with-summary.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('field', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 231) __TwigTemplate_d0a4e06ec4cdc862487a9e59e7ee55e6->block_node_content(Array, Array) (Line: 171) Twig\Template->displayBlock('node_content', Array, Array) (Line: 91) __TwigTemplate_fb45c12c057c90d6dad87acc3f8af627->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 51) __TwigTemplate_d0a4e06ec4cdc862487a9e59e7ee55e6->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/content/node--teaser.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('node', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 60) __TwigTemplate_b5820ae2fc9ac809d8bb920432eaa798->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/contrib/classy/templates/views/views-view-unformatted.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('views_view_unformatted', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 129) __TwigTemplate_c1babb60e112ad993125dc5af5a5b779->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/views/views-view--site-search--page-1.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('views_view__site_search__page_1', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array, ) (Line: 238) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\{closure}() (Line: 592) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->executeInRenderContext(Object, Object) (Line: 239) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->prepare(Array, Object, Object) (Line: 128) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->renderResponse(Array, Object, Object) (Line: 90) Drupal\Core\EventSubscriber\MainContentViewSubscriber->onViewRenderArray(Object, 'kernel.view', Object) call_user_func(Array, Object, 'kernel.view', Object) (Line: 111) Drupal\Component\EventDispatcher\ContainerAwareEventDispatcher->dispatch(Object, 'kernel.view') (Line: 186) Symfony\Component\HttpKernel\HttpKernel->handleRaw(Object, 1) (Line: 76) Symfony\Component\HttpKernel\HttpKernel->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 58) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\Session->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 48) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\KernelPreHandle->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 191) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->fetch(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 128) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->lookup(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 82) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 270) Drupal\shield\ShieldMiddleware->bypass(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 137) Drupal\shield\ShieldMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 48) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\ReverseProxyMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 51) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\NegotiationMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 51) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\StackedHttpKernel->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 704) Drupal\Core\DrupalKernel->handle(Object) (Line: 19) - Warning: Undefined array key 0 in Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances() (line 389 of modules/contrib/footnotes/src/Plugin/Filter/FootnotesFilter.php).

Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances('<em>Plowing on Sunday</em>, from about 1934The drawing is undated, but the image appeared on the cover of the first edition of Sterling North’s novel Plowing on Sunday (New York: Macmillan, 1934)., was described as Grant Wood’s “finest drawing to date” when it was offered to the RISD Museum for consideration in 1937Letter from Maynard Walker, Walker Galleries, New York, to Constance M. Place, Museum of Art, RISD, February 25, 1937. The drawing was purchased by the Museum president, Mrs. Murray Danforth, for $750, a sum that reflected the limited number and availability of Wood’s works at this time. Mrs. Danforth officially made the drawing a gift to the Museum in January 1938.. The squared-off close-up of a farmer drinking from an earthenware jug was purchased by RISD’s president, Helen M. Danforth, who gave it to the collection the following year, around the time Wood visited Providence. Speaking to a capacity crowd at RISD’s Memorial Hall on a January evening, Wood stressed the importance of regional art schools and expressed his belief that small groups were now merging to make a more democratic national artWood’s lecture, which was introduced by painter John Frazier to a “large audience of artists, art students, and art lovers,” was reported in the Providence Journal article “American Artist Speaks of Work: Grant Wood, Midwestern Painter, Addresses Group at Design School,” January 22, 1938. In a letter to RISD president Mrs. Murray Danforth, former interim director Miriam Banks reported: “I have never seen Memorial Hall crowded to such capacity before on any like occasion. Every available seat on the floor was taken and the gallery filled also” (RISD Archives, Directors’ Correspondence files).. Although a leading painter of the American scene, Wood was careful to distinguish between art that advocated “a concentration on local peculiarities” and one that acknowledged important differences between the various regions of AmericaIn 1937, Wood commented on American literary regionalism, stating that “it has been a revolt against cultural nationalism—that is the tendency of artists to ignore or deny the fact that there are important differences, psychologically and otherwise, between the various regions of America. But this does not mean that Regionalism, in turn, advocates a concentration on local peculiarities; such an approach results in anecdotalism and local color” (handwritten commentary on a typed proposal by “the members of English 293, October, 1937,” Grant Wood Scrapbook 02, Grant Wood 1935–1939; University of Iowa Libraries, Figge Art Museum Grant Wood Digital Collection).. He de-emphasized the term “Regionalism” in his RISD talk, insisting it was “not geographic accent but sincere emotion and vitality that distinguish fine painting.”From The Providence Journal, January 22, 1938: “The movement, exemplified by such men as Charles Burchfield, John Steuart Curry, Reginald Marsh and Thomas Benton, who were through their individual techniques each expressing his particular environment was given the name Regionalism. Mr. Wood feels that since it is not geographic accent but sincere emotion and vitality which distinguish fine painting, the term Regionalism is unfortunate.” By 1938, Wood was widely recognized for the narrative appeal of paintings such as <a href="http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/artwork/6565"><em>American Gothic</em></a>, his apotropaic depiction of a father and daughter in front of their Iowa farmhouse. But Wood had long explored more abstract formal solutions in his pursuit of an original style that embraced native subject matter. In <em>Plowing on Sunday</em>, he elevated the figure in importance but diminished individuality in favor of a simplified composition that embedded universal qualities in an American motif. Later, in his 1936 painting <a href="https://reynoldahouse.emuseum.com/objects/12/spring-turning"><em>Spring Turning</em></a>, he reduced the farmer and plow to mere notations, stitching them to the edge of the green and brown quilt of a sculpted Midwestern landscape. Commissioned as the cover design for Sterling North’s eponymous 1934 novel, <em>Plowing on Sunday</em> depicted Stud Brailsford, “a strong man whose wishes and fancies and material ambitions are real and on a human scale.”K. W. (Kenneth White?), review of Sterling North, Plowing on Sunday, in The Saturday Review of Literature, December 15, 1934, 374. North had described Brailsford as a man with a leonine head and mass of graying curls, but the light wavy hair, high cheekbones, and square jaw of Wood’s plowman read as a stylized adaptation of <a href="https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/items/detail/john-steuart-curry-and-grant-wood-8657">the artist’s own features</a>.Wood appears in his preferred attire in a photograph with fellow artist John Steuart Curry, ca. 1932. (Accessible at https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/items/detail/john-steuart-curry-and-grant-wood-8657.) It is related to <a href="http://www.crma.org/Content/Collection/Grant-Wood.aspx">a self-portrait Wood drew in 1932</a>, in which he appeared next to a windmill, wearing the bib overalls he favored.Wood wears a light-colored shirt and bib overalls in his 1932 Self-Portrait (charcoal and pastel on paper; 14 1/2 x 12 in.; Cedar Rapids Art Museum, Cedar Rapids, Iowa), accessible at http://www.crma.org/Content/Collection/Grant-Wood.aspx. This drawing appears to be the study for a painted Self Portrait, 1932–1941 (oil on Masonite panel, 14 3/4 x 12 3/8 in., Figge Art Museum, Davenport, Iowa), in which he appears in a dark shirt. (Accessible at http://figgeartmuseum.org/getattachment/e7bb49f1-d08c-45d2-882e-575d14f729a4/Self-Portrait-65-0001.aspx?maxsidesize=300.) For both drawings he used brown paper as the support, utilizing its color to achieve an overall earth-tone that unified the composition and reinforced the connection between the figure and the land. In <em>Plowing on Sunday</em>, he restricted his media to black conté crayon, ink, and gouache, which he effectively mixed to suggest indigo. Fine webs of diagonal cross-hatching suggest weight, density, and light. Wood varies these patterns to brighten the horizon and to model the plowman’s arms and face. Elsewhere, by deftly shifting his additive technique to imperceptible directional marks, he coaxes an appearance of “tooth” from the smooth paper to create a softer, fabric-like effect for the shirt and denim overalls. In the upper sky, Wood maximizes the coverage of his medium to generate a darkened sky and to force the sharp outlines of the head and water jug into relief. Rendered in a technique that recalls Georges Seurat’s landscape and figural compositions, the plowman emerges as a stoic, sculptural form in an artistic genealogy that ranges from Giotto’s solid peasants to the working men of WPA friezes. Brady M. Roberts notes parallels between Wood’s techniques and those of Seurat in the essay “The European Roots of Regionalism” in Grant Wood: An American Master Revealed (Portland, Oregon: Pomegranate, 1995), 2. In note 9 on page 227 of When Tillage Begins, Other Arts Follow: Grant Wood and Christian Petersen Murals (Ames, Iowa: University Museums, Iowa State University, 2006), Lea Rosson DeLong cites a letter from Wood’s student Leata Rowan, who wrote that Giotto was one of the artists whom Wood taught in his classes on mural painting at the University of Iowa (January 12, 1934, Papers of Edward Rowan, Archives of American Art, reel D 141, fr. 89-01). Paul Signac quoted Edgar Degas’s comment to Seurat upon viewing La Grande Jatte: “You have been in Florence, you have. You have seen the Giottos” (cited by Robert L. Herbert, Georges Seurat, 1859–1891, 174 [New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art and Abrams, 1991]). This effect reinforces the plowman’s connection to his environment and confers a sense of action frozen in time. Wood’s use of brown wrapping paper for both finished drawings and mural preparation was intentional, and he advised his students to use this inexpensive material to encourage experimentation. In 1934 he developed <a href="http://archive.inside.iastate.edu/2004/0116/wood.shtml">a suite of illustrations on brown paper</a> for a limited edition of Sinclair Lewis’s novel <em>Main Street</em>, and showed slides of those drawings at the RISD lecture.The Providence Journal, op. cit., reported that Wood showed slides of his works, including the Main Street illustrations, following the RISD lecture. That commission is Lea Rosson Delong’s subject in Grant Wood’s Main Street: Art, Literature, and the American Midwest (Ames, Iowa: University Museums, Iowa State University, 2004). Like the plowman’s, the heads and upper torsos of Lewis’s characters nearly fill their frames, and their hands and arms indicate representative gestures. While their expressions reveal distinct personalities, the plowman, in contrast, has veiled eyes and no psychologically distinguishing characteristics other than the strong contours of the face and head. By minimizing detail, as he did in his paintings of the late 1930s, Wood transformed his own likeness into a plowman who is Everyman, dressed in the farm uniform that was both democratic and anonymous in its ubiquity. In keeping with his program of simplification, Wood further reduced the imagery of <em>Plowing on Sunday</em> by eliminating the plow, the tool that served as both the icon and metaphor for the activity of tilling the earth. In <em>Plowing on Sunday</em> he introduces the reins at the lower corner of the picture to imply both the farm animals and the instrument they control, and uses the field and low horizon to reinforce the symbolic and decorative value of the leather straps. He follows their taut lines with a wavy pattern of plowed furrows and marks the border of the field with a parallel march of tiny white fence posts. Barely visible on the horizon are a classic Iowa barn and windmill, selective decorative marks that are intentional references to the rural architecture whose extinction Wood feared.The windmill is a prominent element in the two self-portraits made by Wood (cited in endnote 7). Wanda Corn, on page 126 of Grant Wood: The Regionalist Vision (New Haven: Minneapolis Museum of Art and Yale University Press, 1983), notes that Wood “had become particularly attached to the windmill, a familiar landmark in the Midwest, which he feared was becoming extinct,” and that he always found a way to work it into his compositions as a type of signature. Wood re-utilized and expanded the plowman image after he became director of the Iowa’s Public Works of Art Projects in 1934. A full-scale variant of the farmer, posed with his plow and its resting team of horses, drinks from a water jug in the central panel of <em>Breaking the Prairie Sod</em>, Wood’s mural cycle for the Iowa State University Library at Ames.Breaking the Prairie, 1937 (oil on canvas, center panel: 132 x 279 in.; The Iowa State University Library, Ames, Iowa; accessible at https://isuartandhistory.files.wordpress.com/2011/06/copy-of-images-014.jpg). There is also a finished drawing for this mural: Breaking the Prairie, ca. 1935–1937 (colored pencil, chalk, and pencil on brown paper; 22 3/4 x 80 1/4 in.; The Whitney Museum of American Art, Gift of Mr. & Mrs. George D. Stoddard). <em>Maureen O’Brien Curator, Painting and Sculpture</em> ') (Line: 116) Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->process('<em>Plowing on Sunday</em>, from about 1934The drawing is undated, but the image appeared on the cover of the first edition of Sterling North’s novel Plowing on Sunday (New York: Macmillan, 1934)., was described as Grant Wood’s “finest drawing to date” when it was offered to the RISD Museum for consideration in 1937Letter from Maynard Walker, Walker Galleries, New York, to Constance M. Place, Museum of Art, RISD, February 25, 1937. The drawing was purchased by the Museum president, Mrs. Murray Danforth, for $750, a sum that reflected the limited number and availability of Wood’s works at this time. Mrs. Danforth officially made the drawing a gift to the Museum in January 1938.. The squared-off close-up of a farmer drinking from an earthenware jug was purchased by RISD’s president, Helen M. Danforth, who gave it to the collection the following year, around the time Wood visited Providence. Speaking to a capacity crowd at RISD’s Memorial Hall on a January evening, Wood stressed the importance of regional art schools and expressed his belief that small groups were now merging to make a more democratic national artWood’s lecture, which was introduced by painter John Frazier to a “large audience of artists, art students, and art lovers,” was reported in the Providence Journal article “American Artist Speaks of Work: Grant Wood, Midwestern Painter, Addresses Group at Design School,” January 22, 1938. In a letter to RISD president Mrs. Murray Danforth, former interim director Miriam Banks reported: “I have never seen Memorial Hall crowded to such capacity before on any like occasion. Every available seat on the floor was taken and the gallery filled also” (RISD Archives, Directors’ Correspondence files).. Although a leading painter of the American scene, Wood was careful to distinguish between art that advocated “a concentration on local peculiarities” and one that acknowledged important differences between the various regions of AmericaIn 1937, Wood commented on American literary regionalism, stating that “it has been a revolt against cultural nationalism—that is the tendency of artists to ignore or deny the fact that there are important differences, psychologically and otherwise, between the various regions of America. But this does not mean that Regionalism, in turn, advocates a concentration on local peculiarities; such an approach results in anecdotalism and local color” (handwritten commentary on a typed proposal by “the members of English 293, October, 1937,” Grant Wood Scrapbook 02, Grant Wood 1935–1939; University of Iowa Libraries, Figge Art Museum Grant Wood Digital Collection).. He de-emphasized the term “Regionalism” in his RISD talk, insisting it was “not geographic accent but sincere emotion and vitality that distinguish fine painting.”From The Providence Journal, January 22, 1938: “The movement, exemplified by such men as Charles Burchfield, John Steuart Curry, Reginald Marsh and Thomas Benton, who were through their individual techniques each expressing his particular environment was given the name Regionalism. Mr. Wood feels that since it is not geographic accent but sincere emotion and vitality which distinguish fine painting, the term Regionalism is unfortunate.” By 1938, Wood was widely recognized for the narrative appeal of paintings such as <a href="http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/artwork/6565"><em>American Gothic</em></a>, his apotropaic depiction of a father and daughter in front of their Iowa farmhouse. But Wood had long explored more abstract formal solutions in his pursuit of an original style that embraced native subject matter. In <em>Plowing on Sunday</em>, he elevated the figure in importance but diminished individuality in favor of a simplified composition that embedded universal qualities in an American motif. Later, in his 1936 painting <a href="https://reynoldahouse.emuseum.com/objects/12/spring-turning"><em>Spring Turning</em></a>, he reduced the farmer and plow to mere notations, stitching them to the edge of the green and brown quilt of a sculpted Midwestern landscape. Commissioned as the cover design for Sterling North’s eponymous 1934 novel, <em>Plowing on Sunday</em> depicted Stud Brailsford, “a strong man whose wishes and fancies and material ambitions are real and on a human scale.”K. W. (Kenneth White?), review of Sterling North, Plowing on Sunday, in The Saturday Review of Literature, December 15, 1934, 374. North had described Brailsford as a man with a leonine head and mass of graying curls, but the light wavy hair, high cheekbones, and square jaw of Wood’s plowman read as a stylized adaptation of <a href="https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/items/detail/john-steuart-curry-and-grant-wood-8657">the artist’s own features</a>.Wood appears in his preferred attire in a photograph with fellow artist John Steuart Curry, ca. 1932. (Accessible at https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/items/detail/john-steuart-curry-and-grant-wood-8657.) It is related to <a href="http://www.crma.org/Content/Collection/Grant-Wood.aspx">a self-portrait Wood drew in 1932</a>, in which he appeared next to a windmill, wearing the bib overalls he favored.Wood wears a light-colored shirt and bib overalls in his 1932 Self-Portrait (charcoal and pastel on paper; 14 1/2 x 12 in.; Cedar Rapids Art Museum, Cedar Rapids, Iowa), accessible at http://www.crma.org/Content/Collection/Grant-Wood.aspx. This drawing appears to be the study for a painted Self Portrait, 1932–1941 (oil on Masonite panel, 14 3/4 x 12 3/8 in., Figge Art Museum, Davenport, Iowa), in which he appears in a dark shirt. (Accessible at http://figgeartmuseum.org/getattachment/e7bb49f1-d08c-45d2-882e-575d14f729a4/Self-Portrait-65-0001.aspx?maxsidesize=300.) For both drawings he used brown paper as the support, utilizing its color to achieve an overall earth-tone that unified the composition and reinforced the connection between the figure and the land. In <em>Plowing on Sunday</em>, he restricted his media to black conté crayon, ink, and gouache, which he effectively mixed to suggest indigo. Fine webs of diagonal cross-hatching suggest weight, density, and light. Wood varies these patterns to brighten the horizon and to model the plowman’s arms and face. Elsewhere, by deftly shifting his additive technique to imperceptible directional marks, he coaxes an appearance of “tooth” from the smooth paper to create a softer, fabric-like effect for the shirt and denim overalls. In the upper sky, Wood maximizes the coverage of his medium to generate a darkened sky and to force the sharp outlines of the head and water jug into relief. Rendered in a technique that recalls Georges Seurat’s landscape and figural compositions, the plowman emerges as a stoic, sculptural form in an artistic genealogy that ranges from Giotto’s solid peasants to the working men of WPA friezes. Brady M. Roberts notes parallels between Wood’s techniques and those of Seurat in the essay “The European Roots of Regionalism” in Grant Wood: An American Master Revealed (Portland, Oregon: Pomegranate, 1995), 2. In note 9 on page 227 of When Tillage Begins, Other Arts Follow: Grant Wood and Christian Petersen Murals (Ames, Iowa: University Museums, Iowa State University, 2006), Lea Rosson DeLong cites a letter from Wood’s student Leata Rowan, who wrote that Giotto was one of the artists whom Wood taught in his classes on mural painting at the University of Iowa (January 12, 1934, Papers of Edward Rowan, Archives of American Art, reel D 141, fr. 89-01). Paul Signac quoted Edgar Degas’s comment to Seurat upon viewing La Grande Jatte: “You have been in Florence, you have. You have seen the Giottos” (cited by Robert L. Herbert, Georges Seurat, 1859–1891, 174 [New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art and Abrams, 1991]). This effect reinforces the plowman’s connection to his environment and confers a sense of action frozen in time. Wood’s use of brown wrapping paper for both finished drawings and mural preparation was intentional, and he advised his students to use this inexpensive material to encourage experimentation. In 1934 he developed <a href="http://archive.inside.iastate.edu/2004/0116/wood.shtml">a suite of illustrations on brown paper</a> for a limited edition of Sinclair Lewis’s novel <em>Main Street</em>, and showed slides of those drawings at the RISD lecture.The Providence Journal, op. cit., reported that Wood showed slides of his works, including the Main Street illustrations, following the RISD lecture. That commission is Lea Rosson Delong’s subject in Grant Wood’s Main Street: Art, Literature, and the American Midwest (Ames, Iowa: University Museums, Iowa State University, 2004). Like the plowman’s, the heads and upper torsos of Lewis’s characters nearly fill their frames, and their hands and arms indicate representative gestures. While their expressions reveal distinct personalities, the plowman, in contrast, has veiled eyes and no psychologically distinguishing characteristics other than the strong contours of the face and head. By minimizing detail, as he did in his paintings of the late 1930s, Wood transformed his own likeness into a plowman who is Everyman, dressed in the farm uniform that was both democratic and anonymous in its ubiquity. In keeping with his program of simplification, Wood further reduced the imagery of <em>Plowing on Sunday</em> by eliminating the plow, the tool that served as both the icon and metaphor for the activity of tilling the earth. In <em>Plowing on Sunday</em> he introduces the reins at the lower corner of the picture to imply both the farm animals and the instrument they control, and uses the field and low horizon to reinforce the symbolic and decorative value of the leather straps. He follows their taut lines with a wavy pattern of plowed furrows and marks the border of the field with a parallel march of tiny white fence posts. Barely visible on the horizon are a classic Iowa barn and windmill, selective decorative marks that are intentional references to the rural architecture whose extinction Wood feared.The windmill is a prominent element in the two self-portraits made by Wood (cited in endnote 7). Wanda Corn, on page 126 of Grant Wood: The Regionalist Vision (New Haven: Minneapolis Museum of Art and Yale University Press, 1983), notes that Wood “had become particularly attached to the windmill, a familiar landmark in the Midwest, which he feared was becoming extinct,” and that he always found a way to work it into his compositions as a type of signature. Wood re-utilized and expanded the plowman image after he became director of the Iowa’s Public Works of Art Projects in 1934. A full-scale variant of the farmer, posed with his plow and its resting team of horses, drinks from a water jug in the central panel of <em>Breaking the Prairie Sod</em>, Wood’s mural cycle for the Iowa State University Library at Ames.Breaking the Prairie, 1937 (oil on canvas, center panel: 132 x 279 in.; The Iowa State University Library, Ames, Iowa; accessible at https://isuartandhistory.files.wordpress.com/2011/06/copy-of-images-014.jpg). There is also a finished drawing for this mural: Breaking the Prairie, ca. 1935–1937 (colored pencil, chalk, and pencil on brown paper; 22 3/4 x 80 1/4 in.; The Whitney Museum of American Art, Gift of Mr. & Mrs. George D. Stoddard). <em>Maureen O’Brien Curator, Painting and Sculpture</em> ', 'en') (Line: 118) Drupal\filter\Element\ProcessedText::preRenderText(Array) call_user_func_array(Array, Array) (Line: 111) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doTrustedCallback(Array, Array, 'Render #pre_render callbacks must be methods of a class that implements \Drupal\Core\Security\TrustedCallbackInterface or be an anonymous function. The callback was %s. See https://www.drupal.org/node/2966725', 'exception', 'Drupal\Core\Render\Element\RenderCallbackInterface') (Line: 797) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doCallback('#pre_render', Array, Array) (Line: 386) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 106) __TwigTemplate_4039b6d648e4a30fc59604b38849a688->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 46) __TwigTemplate_d1494d795b4bd5366283e85f3e7729dc->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 43) __TwigTemplate_253b62141ad73ee07345b0067cf59829->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/contrib/classy/templates/field/field--text-with-summary.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('field', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 231) __TwigTemplate_d0a4e06ec4cdc862487a9e59e7ee55e6->block_node_content(Array, Array) (Line: 171) Twig\Template->displayBlock('node_content', Array, Array) (Line: 91) __TwigTemplate_fb45c12c057c90d6dad87acc3f8af627->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array, Array) (Line: 51) __TwigTemplate_d0a4e06ec4cdc862487a9e59e7ee55e6->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/content/node--teaser.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('node', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 60) __TwigTemplate_b5820ae2fc9ac809d8bb920432eaa798->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/contrib/classy/templates/views/views-view-unformatted.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('views_view_unformatted', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array) (Line: 474) Drupal\Core\Template\TwigExtension->escapeFilter(Object, Array, 'html', NULL, 1) (Line: 129) __TwigTemplate_c1babb60e112ad993125dc5af5a5b779->doDisplay(Array, Array) (Line: 394) Twig\Template->displayWithErrorHandling(Array, Array) (Line: 367) Twig\Template->display(Array) (Line: 379) Twig\Template->render(Array, Array) (Line: 40) Twig\TemplateWrapper->render(Array) (Line: 53) twig_render_template('themes/custom/risdmuseum/templates/views/views-view--site-search--page-1.html.twig', Array) (Line: 372) Drupal\Core\Theme\ThemeManager->render('views_view__site_search__page_1', Array) (Line: 445) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array) (Line: 458) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->doRender(Array, ) (Line: 204) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->render(Array, ) (Line: 238) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\{closure}() (Line: 592) Drupal\Core\Render\Renderer->executeInRenderContext(Object, Object) (Line: 239) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->prepare(Array, Object, Object) (Line: 128) Drupal\Core\Render\MainContent\HtmlRenderer->renderResponse(Array, Object, Object) (Line: 90) Drupal\Core\EventSubscriber\MainContentViewSubscriber->onViewRenderArray(Object, 'kernel.view', Object) call_user_func(Array, Object, 'kernel.view', Object) (Line: 111) Drupal\Component\EventDispatcher\ContainerAwareEventDispatcher->dispatch(Object, 'kernel.view') (Line: 186) Symfony\Component\HttpKernel\HttpKernel->handleRaw(Object, 1) (Line: 76) Symfony\Component\HttpKernel\HttpKernel->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 58) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\Session->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 48) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\KernelPreHandle->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 191) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->fetch(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 128) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->lookup(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 82) Drupal\page_cache\StackMiddleware\PageCache->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 270) Drupal\shield\ShieldMiddleware->bypass(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 137) Drupal\shield\ShieldMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 48) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\ReverseProxyMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 51) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\NegotiationMiddleware->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 51) Drupal\Core\StackMiddleware\StackedHttpKernel->handle(Object, 1, 1) (Line: 704) Drupal\Core\DrupalKernel->handle(Object) (Line: 19) - Warning: Undefined array key 0 in Drupal\footnotes\Plugin\Filter\FootnotesFilter->getLinkInstances() (line 388 of modules/contrib/footnotes/src/Plugin/Filter/FootnotesFilter.php).